This article was originally published in a sponsored newsletter.

Since I first started doing cataract surgery 35 years ago, the health of the ocular surface has become better appreciated as one of the most important issues to address for our cataract patients to ensure successful outcomes. It is almost impossible to make patients happy with their resulting comfort and quality of vision if the ocular surface is poor before or after surgery. Most ocular surface issues tend to get lumped into the "dry eye” category, but an important range of epithelial and subepithelial disorders can cause regular and irregular astigmatism also needs to be recognized and addressed before cataract surgery. One of the common problems I see that can lead to the wrong choice of IOL for patients and poor vision after phaco is the presence of cornea avascular pannus (CAP).

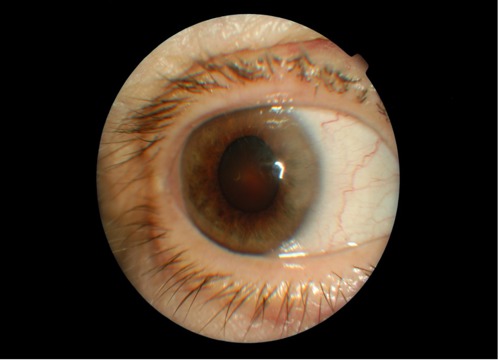

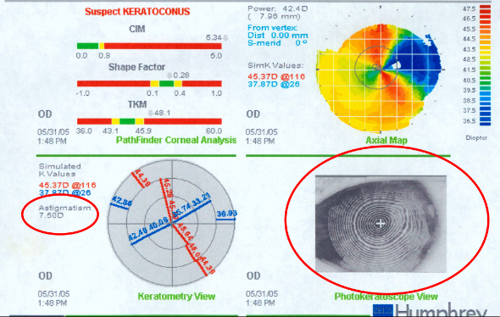

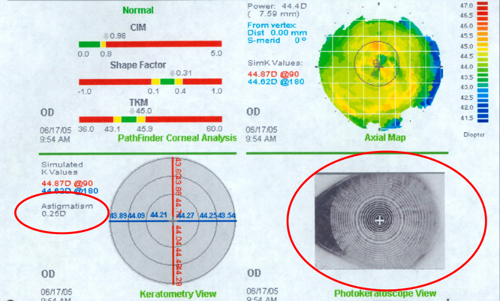

A normal corneal epithelium has three properties that differentiate it from other epithelia: it is transparent, easily wettable and of relatively uniform thickness. CAP, however, represents a thickened area of abnormal epithelium that is contiguous with the limbus and lacks the above qualities of clarity and easy wettability (see Figure 1). It is avascular, opaque, thickened, wets relatively poorly and causes flattening of the cornea on topography, which can lead to regular (and often some irregular) astigmatism (see topography image below in Figure 2). CAP is often associated with other ocular surface problems such as blepharitis and mechanical irritation, and I liken it to a “callus” of the cornea when describing it to patients.

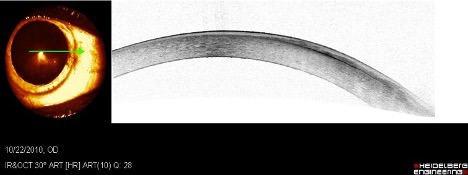

One of the most important characteristics of CAP is that it respects Bowman’s membrane on OCT and remains anterior to it without invading the stroma. This attribute differentiates it from pterygium and solar degenerative changes that may invade the stroma. In the OCT image below (Figure 3), you can see the thickened area of abnormal epithelial/subepithelial pannus that extends from the limbus and remains anterior to Bowman’s.

The fact that these plaques remain anterior to the stroma makes them amenable to complete removal with superficial keratectomy, which I prefer to do at the slit lamp.1 It is relatively easy to slide under the plaque with a 1.25mm angled crescent blade and lift it up like a pizza off the cornea stroma.

Once these lesions are peeled, the topography typically normalizes and remains clear without recurrence (provided any significant preexisting ocular surface issues are addressed before keratectomy). See Figure 4 below that shows the same patient as Figures 1 and 2 after superficial keratectomy. Note that astigmatism is completely resolved.

Most often, the lesion is contiguous with the conjunctiva, which may be disinserted at the limbus when you peel it off (which can lead to some bleeding). This is one thing that differentiates CAP from Salzmann’s nodules which tend to be discrete, multifocal, 1 to 3mm in size, waxy bluish white elevated nodules that are separate from the limbus and each other.2 Most of the CAP cases I have seen have been associated with significant Demodex blepharitis and should be treated and controlled before superficial keratectomy to prevent recurrence.

If you look at the mires on topography, pay attention to their regularity and symmetry and look for areas of asymmetric flattening on topography. It is relatively easy to address this common problem before surgery. It would be a regrettable mistake to put in a high-power toric lens to treat abnormal reversible cornea astigmatism.

References:

- Safran SG. Slit lamp removal of corneal pannus by Steven G. Safran MD. YouTube. August 28, 2019. Accessed February 5, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XrKLLHqHB5I

- Maust HA, Raber IM. Peripheral hypertrophic subepithelial corneal degeneration. Eye Contact Lens. 2003 Oct;29(4):266–269. doi:10.1097/01.icl.0000087489.61955.82