Cataract surgery in normal, healthy eyes is so routine that patient expectations are higher than ever, and most patients expect excellent uncorrected vision after surgery. Given this, it is increasingly important that we as surgeons identify pathology that could affect postoperative outcomes and set the appropriate expectations before surgery. Although insurance companies do not see it as a justifiable expense, it is important to obtain macula OCT on every cataract preop and corneal topography (and aberrometry) are just as important.

When we routinely screen cataract patients with tomography and aberrometry, we will find that some patients with a perfectly normal slit lamp exam have irregular corneas. In this article, I will discuss some of the common sources of irregular corneas that can complicate cataract surgery calculations and outcomes, the preoperative workup, preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative considerations, what diagnostics are needed, the best IOLs to use, and when to consider a femtosecond laser.

SOURCES OF IRREGULAR CORNEAS

Refractive surgery

We all routinely see patients who have had corneal refractive surgery. Older generation lasers had limited to no eye tracking as well as small ablation zones, and this often led to higher-order aberrations due to decentered and/or very small ablations. Patients who have had incisional surgeries such as radial keratotomy (RK), circle or hexagonal keratotomy and automated lamellar keratoplasty often have very irregular corneas and can be very challenging to treat.

Corneal ectasias

Keratoconus, pellucid marginal degeneration and other corneal ectasias can result in irregular corneas that appear anatomically normal on a slit lamp exam but are easy to detect using diagnostic devices that I will discuss below.

Corneal scarring

Corneal scarring due to any etiology (previous infection, trauma, etc.) can also lead to irregularity. These are more obvious, as patients typically offer history of infections or trauma and surgeons will note a scar on the slit lamp exam. It is important to characterize the degree of irregularity caused by the scarring. Some scarring involving the visual axis can be surprising in that a rigid contact lens (rigid gas permeable [RGP], scleral or hybrid lens) can result in very good vision despite significant corneal scarring, indicating that the primary cause of the poor vision is often the corneal irregularity and not the opacity.

Other sources

Severe forms of ocular surface disease or dry eye disease can cause irregular corneas as well. Pterygia and Salzmann’s nodular degeneration are other treatable conditions that cause irregular corneas.

PREOPERATIVE WORKUP

Overview

In any patient with an irregular cornea, careful preoperative evaluation is exceedingly imperative. It is important to be clear with the patient that they have two issues: a cataract and an irregular cornea. One of those issues will be fixed with cataract surgery, and the other will not. The goal of a thorough preoperative evaluation is to determine which is the primary cause of poor vision and which is secondary, but this is not always possible. History, diagnostic testing and a thorough exam are all useful in making this determination.

History

History is important. First, we want to ask all cataract patients if they have a history of any ocular surgery, infections or trauma. This can be our first clue to take a closer look. If history is negative but our diagnostic testing (tomography and/or aberrometry) is our first clue that the patient has an irregular cornea, then history taking becomes valuable in assessing whether the current complaint of poor vision is most likely from the cataract or the cornea.

If the corneal condition is progressive, characterizing the onset of poor vision and timeline can help us differentiate between cataract and corneal causes. For example, we often diagnose cataract-aged patients with mild forms of keratoconus that have gone undetected their entire lives since they have never had a reason to have a tomography. In these cases, eliciting a history of spectacle best-corrected vision of 20/20 before cataract symptom onset is reassuring that they can expect a good outcome after cataract surgery.

In contrast, a 50-year-old patient with mild cataracts and a new diagnosis of pellucid marginal degeneration may have a timeline of rapid deterioration of vision in the last 1 to 2 years, and it can be difficult to discern if the progression was due to corneal or lenticular changes. In these cases, reviewing old records can be helpful. Asking about night vision issues (cataract more than cornea) vs distortion and blur (possibly more corneal in origin) can also help.

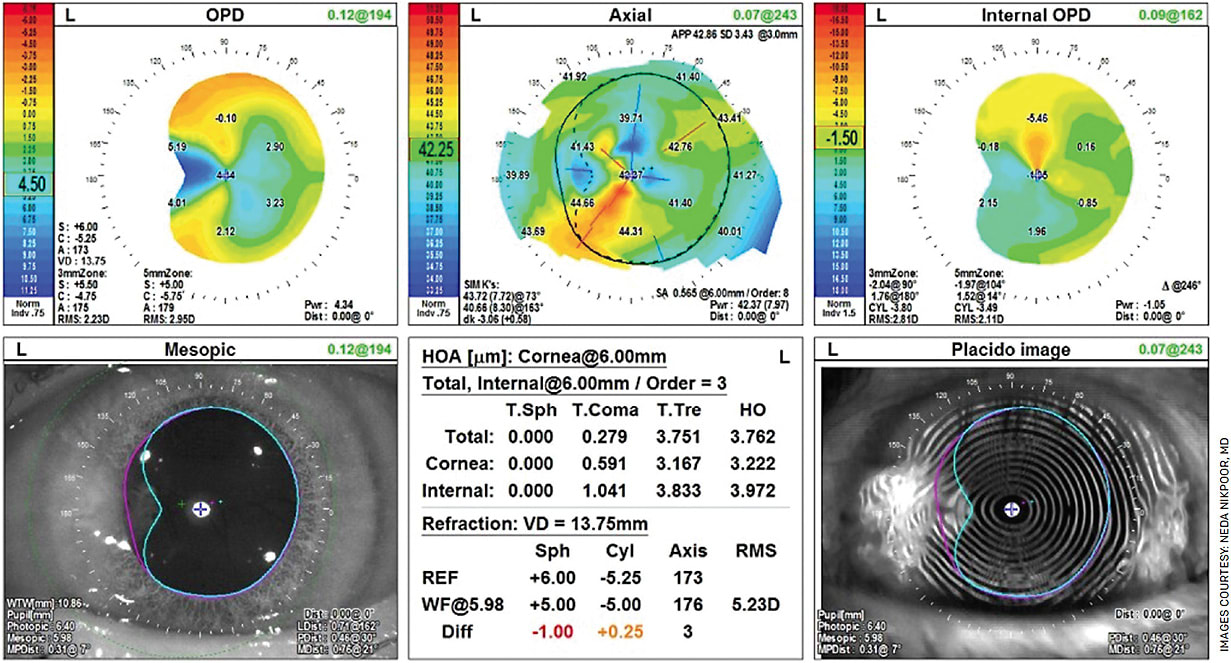

Diagnostic devices

Diagnostic devices give the surgeon information and serve as a teaching tool. For instance, in corneal refractive surgery patients, decentered ablations are very obvious on routine tomography, and these scans, as well as aberrometry, can be a useful visual tool in showing patients why they may not see well after surgery. I find that patients have often lived with coma and other aberrations for years yet never mentioned them, but when I describe a comet or tail, they say that is exactly what they see and have for years. The iTrace Patient Education display (Tracey Technologies) is particularly helpful to me for these patients (Figure 1).

Once the patient confirms they see the aberration, then you can discuss whether they have any new symptoms attributable to a cataract and, if so, how their cataract symptoms will improve or resolve but their distortion due to higher-order aberrations will remain. Placido disc imaging (eg, Nidek OPD-Scan III, Oculus Keratograph and Zeiss Atlas) can be very useful in detecting and explaining irregularity due to pterygium, nodular degeneration and severe dry eye. Once detected, dry eye, pterygium and nodular degeneration can and should be treated before cataract surgery if they are causing significant irregularity and distortion of central mires (Figure 2).

When it’s still hard to determine the culprit

Sometimes, even with careful preoperative assessment of uncorrected and spectacle best-corrected vision, history and numerous diagnostic tests, it can be difficult to differentiate the degree of blurry vision attributable to the cornea vs the lens. In these cases, I find RGP over-refraction to be indispensable.

If an RGP over-refraction does not improve vision at all, the likely culprit is the lens (or some other pathology besides the anterior cornea). If RGP over-refraction improves vision, the last thing we want to do is cataract surgery because the problem lies in the cornea. Inevitably, sometimes we can miss this, and RGP over-refraction can be equally useful after surgery when deciding if someone’s poor quality vision is due to the ocular surface (irregular cornea due to dry eye, anatomy, etc.) or the IOL (eg, in the case of diffractive IOLs). This is admittedly time consuming, but there is no replacement for this test.

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

Procedure before cataract surgery

Once we have determined that someone has an irregular cornea, what do we do with that information? What corneal conditions do we treat and how does that affect our IOL choice?

Some experts advocate for topography-guided PRK or LASIK to correct irregularities in the cornea with the aim of optimizing the ocular surface to improve candidacy for advanced technology IOLs (such as multifocal/trifocal/extended depth of focus lenses). Others even recommend Intacs corneal implants (Addition Technology) and corneal collagen crosslinking (CXL) for keratoconus patients before cataract surgery.

In my experience, CXL can be a bit unpredictable, and the time course is often too long for patients. Some of these corneas can take a year or more to stabilize after corneal surgery, and some studies show flattening after CXL for as many as 7 years. Most patients already have a visually significant cataract at the time of the consult, and they usually prefer to avoid additional delays to surgery. There is also a cost associated with these additional procedures that cannot be ignored.

Given the great IOL options for patients with irregular corneas, I generally do not recommend a reparative corneal procedure before cataract surgery unless it is the only option, or if the cataract is very mild. One exception is radial keratotomy (RK) patients with significant fluctuation or progressive ectasia in keratoconus or pellucid marginal degeneration. I will recommend CXL for these patients. For RK patients specifically, I will let them know that the goal of off-label CXL is to reduce the amplitude of their fluctuations and that we will wait for corneal/topographic stability before proceeding with cataract surgery.

What should our refractive target be?

In general, I tend to err on the side of myopia. Patients with irregular corneas, especially patients with penetrating keratoplasties for example, tend to have hyperopic surprises, so aiming for a myopic target (ie, -1 to -3 depending on the degree of corneal curvature irregularity), can often result in a closer to plano outcome. However, I often use multiple formulas in these cases to help determine the IOL power and heavily counsel my patients that there may be a postoperative refractive surprise requiring glasses or hard contact lens use. The Light Adjustable Lens (LAL, RxSight) technology has been a great adjunct in my practice for these challenging cases to better nail the refractive target. Additionally for patients who are PRK candidates, myopic PRK is more predictable than hyperopic PRK, so a myopic outcome is more easily correctable.

Finally, patients are generally more satisfied postoperatively if they are free of spectacles for at least one range of vision, so even if they are not PRK candidates, a myopic outcome will at least afford them good uncorrected near vision in most cases. I extensively counsel these patients about the risk of refractive surprises and the need for eyeglasses, contact lenses, laser enhancements or IOL exchanges to correct any residual refractive error. I use their diagnostic devices as visual aides to help them understand why their case is particularly challenging.

PERIOPERATIVE AND INTRAOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

Overview

We have amazing technology at our disposal to deliver great outcomes for these patients. First and foremost, we must set realistic expectations. However, there is no need to default to a monofocal IOL and prescribe glasses to everyone with an irregular cornea. We can achieve great uncorrected vision for these patients with the right tools, some of which I will discuss below.

Tools for hitting refractive targets

We must optimize the ocular surface and repeat IOL and other measurements to ensure consistency and stability. Next, we need to use modern IOL formulas and calculators for post-refractive and keratoconus patients. Surgical planning software can be used to improve workflow. For example, I use Veracity (Zeiss) for my surgical planning, which has the Barrett formula, Kane formula (great for keratoconus) and post-refractive calculators built into the software.

Also, I have found the ORA (Alcon) (the only available intraoperative aberrometer) to be the most accurate way to measure aberrated eyes. I use ORA for all of these patients. Sometimes, ORA will give an error or a caution and will not give a reading, even when everything is done properly. I find this to occur regularly in post-RK and other highly aberrated corneas. For these patients, I take several measurements, ignore the caution and look at the recommended lens. I compare this to my preoperative calculations and use my judgment as to whether to change the IOL power and by how much.

Surgical technique is critical when using ORA. This means keeping the cornea well lubricated in the preoperative holding area and in surgery. It is also important to inflate the eye to a physiologic IOP and check with a tonometer. Any pooling or pressure from the speculum needs to be addressed, especially in high myopes, as these can falsely affect measurements.

Choosing an IOL

Often, different devices will lead to conflicting recommendations for lens power, so I strongly prefer the LAL for any irregular cornea patient who has reasonable spectacle corrected vision, reasonable expectations and is otherwise a candidate for the LAL technology. It can be exceedingly difficult to determine the correct power for sphere and cylinder, and the correct axis of astigmatism can be even more challenging to measure. For this reason, adjustability takes a lot of the guesswork out of calculating the correct IOL power.

Some corneas are too irregular. In those cases, historically, we have only had monofocal IOLs to fall back on, but we now have the IC-8 Apthera small aperture IOL (Bausch + Lomb). It remains to be seen where the line is at which we recommend a small-aperture IOL. At our practice, we still recommend the LAL as our first-line IOL if the patient has historically seen well with glasses or soft contact lenses before developing a cataract. If a patient is truly borderline in both eyes, one approach is to plan an Apthera in the non-dominant eye and plan LAL in the dominant eye. Determining which eye to operate on first depends on the degree of irregularity. One challenge with Apthera is the fixed power and the inherent difficulty in calculating the needed IOL power. The pinhole optics help overcome this to some extent, but there is still a risk of needing to exchange or enhance these patients if they are very off target.

A small subset of patients with irregular corneas are not candidates for either of these lenses or cannot afford either of the lenses. For those patients, a monofocal IOL is preferred — they can expect to wear rigid contact lenses after surgery for the best vision.

Historically, the recommendation has been to avoid toric IOLs in cases of irregular astigmatism, primarily because of concern of difficulty fitting patients with RGPs after surgery. Skilled optometrists are capable of fitting rigid contact lenses with toricity on the back of the lens for patients with toric IOLs, so this is not an absolute contraindication.

In general, I avoid fixed power toric lenses for the above-mentioned reasons — difficulty measuring and calculating power — but I am less concerned about LAL. With the LAL, you start with a monofocal without toricity and choose after implantation whether to add toricity, so you have eliminated the cataract as a cause for poor vision before deciding whether to add toricity to the IOL. For this reason, LAL and Apthera patients are much easier to fit with a rigid contact lens after surgery should they need it. LAL, Apthera and a monofocal IOL are all reasonable options for patients with irregular corneas.

When to consider a femtosecond laser

Opinions vary regarding the value of laser-assisted cataract surgery. At our practice, we use laser for all of our advanced technology IOLs, but I avoid using the laser for any patients who have had RK or have significant corneal scarring. There is a concern that epithelial plugging of RK incisions or any other corneal scarring can lead to skip lesions, leading to increased risk of capsular tags and tears. Additionally, careful placement of corneal incisions is key, especially in RK patients, and this is sometimes more challenging with the laser.

Furthermore, many patients with irregular corneas have abnormal corneal elasticity and anatomy, and patients with keratoconus, history of corneal transplants and other corneal disorders can often have leaky incisions that require a single nylon suture. When in doubt, I always place a suture in these complex cornea cases.

Visualization can be another challenge in complex cornea cases, so I have a low threshold to use trypan blue. For cases of severe corneal scarring, indirect light with a vitreoretinal light pipe can be very useful and can be held by an assistant.

CONCLUSION

Patients with irregular corneas have unique challenges, but we have so much technology at our disposal to provide excellent outcomes for these patients. They have often lived with mediocre vision for years and are very grateful when you can improve their quality of life by providing them with excellent uncorrected vision.

By properly screening patients with preoperative tomography, we can identify the cause of irregularity before surgery, develop a treatment plan and set appropriate expectations. With the tools discussed above, we can give patients with irregular corneas very good vision. OM