A 24-year-old female with no significant past medical history presented with a headache and decreased visual acuity in the right eye. Approximately 2 weeks prior, she had developed a fever, chills and gastrointestinal symptoms. She was diagnosed with viral gastroenteritis following evaluation by her primary-care physician. Approximately 1 week later, she developed an occipital headache and central scotoma in the right eye.

WORKUP AND DIAGNOSIS

In the emergency department, her CBC and CMP were within normal limits. MRI orbit, CT head and CT angiography were unremarkable. Antinuclear antibody, Quantiferon gold, RPR and ACE testing returned negative.

Ocular examination of our patient revealed the following:

- Distance visual acuity without correction: 20/100 OD and 20/20 OS

- Pupils: Briskly reactive with no APD OU

- IOP: 14 mm Hg OD, 15 mm Hg OS

- Anterior segment exam: Unremarkable

- Posterior segment exam: Multiple flat creamy yellow lesions noted posterior to the equator OU, with foveal involvement OD (Figure 1).

Based on these findings, we obtained the following imaging in clinic:

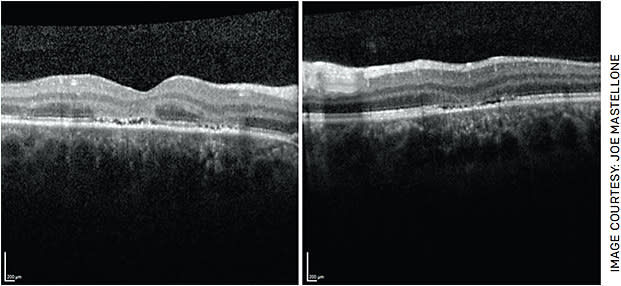

- OCT of the macula, which revealed patchy hyperreflectivity of the outer nuclear layer with loss of the ellipsoid zone in the fovea and inferior to the fovea in the right and left eyes, respectively (Figure 2).

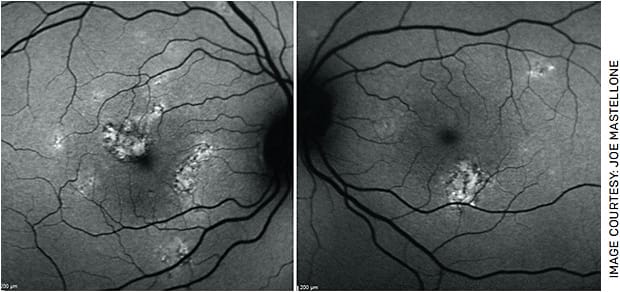

FIGURE 2. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the macula OU demonstrating focal areas of hyperreflectivity involving the outer nuclear layer with loss of the underlying ellipsoid zone in the right eye (left image). There is overlying depression of the inner retinal layers in the left eye (right image). - Fundus autofluorescence (FAF), which demonstrated patchy areas of hyper-autofluorescence in the fovea OD and inferior to the fovea OS (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3. Fundus autofluorescence photos OU show patchy areas of hyper-autofluorescence in the fovea OD (left image) and inferior to the fovea OS (right image).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Our patient’s fundus findings were most consistent with non-infectious posterior uveitis, such as serpiginous choroidopathy, multiple evanescent white dot syndrome, multifocal choroiditis or acute multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy (APMPPE). These diseases share the common feature of white-yellow lesions in the retina, which indicate localized inflammation within the outer retina, choriocapillaris, choroid and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). Given the combination of bilateral creamy placoid lesions in the posterior pole, outer retinal hyperreflectivity on OCT and hyper-autofluorescence on FAF in a younger patient following a viral prodrome, we diagnosed our patient with APMPPE.

Serpiginous choroidopathy would present with a more chronic and severe clinical course, with lesions spreading centrifugally in a serpiginous fashion. Multiple evanescent white dot syndrome typically does not manifest in both eyes. In multifocal choroiditis, the nidus of inflammation is localized to the choroid and is often accompanied by choroidal neovascular membranes, which were not observed here. Other etiologies of uveitis that may present with placoid lesions were ruled out with negative laboratory workup for sarcoidosis, tuberculosis and syphilis.1

APMPPE

APMPPE is an inflammatory chorioretinopathy classified as non-infectious posterior uveitis. It is rare, occurring in 0.15 cases per 100,000 people. APMPPE has no gender predilection and is most commonly seen in the second through the fourth decades of life.2 Although APMPPE is primarily an ocular disease, central nervous system (CNS) and systemic manifestations can occur.3

Rapid onset, bilateral, asymmetric involvement of the eyes is characteristic, and involvement of the contralateral eye can occur several days apart. Anterior segment exam may reveal mild cell and flare or anterior vitreous cell in 50% of cases.4,5 Posterior segment exam should show multiple bilateral creamy yellow-white placoid lesions in the posterior pole of the eye.5

Most patients with APMPPE report a preceding viral or flu-like illness, as seen in our patient. APMPPE is associated with a number of infectious etiologies, such as strep pyogenes, influenza, coxsackie-B, hepatitis B, Lyme disease, mumps and tuberculosis. Also, APMPPE is associated with post-vaccination, certain genetic haplotypes and several inflammatory conditions. Most notably, APMPPE is associated with CNS vasculitis, the most common APMPPE-associated neurological complication.5

In a review by Algahtani et al, CNS vasculitis comprised 50% of the neurological complications reported in APMPPE.6 Therefore, head imaging of all patients with suspected APMPPE is imperative, as CNS vasculitis can be fatal.

Although the etiology of APMPPE is unclear, it likely arises from an occlusive vasculitis secondary to an inflammatory or autoimmune process at the level of the choriocapillaris and inner choroid. Ischemic injury of the RPE and photoreceptors then leads to inflammation of the outer retina and choroid.7,8 The RPE atrophy and hyperpigmentation will follow with resolution of acute disease.

Visual recovery is expected in 6 to 8 weeks. Although 75% of patients will achieve a visual acuity of 20/40 or better, visual recovery is often incomplete.9 Several factors have been documented to affect visual prognosis, including foveal involvement, age, unilaterality, interval involvement of the second eye greater than 6 months later and recurrence.10

Treatment with steroids is recommended during an acute flare to reduce retina damage. In those with recurrent disease, a steroid-sparing agent should be used, such as mycophenolate mofetil.5 Recurrent or chronic cases of APMPPE are more suggestive of relentless placoid choroiditis, which is managed with systemic immunomodulatory therapy.11

BACK TO OUR PATIENT

Our case presented with classic findings of APMPPE: a young patient with a preceding viral prodrome, rapid onset central scotoma OD and bilateral placoid lesions. Our patient was treated with 60 mg of prednisone for 3 days followed by 40 mg daily. Over the next 2 weeks, visual acuity improved from 20/100 to 20/30 in the right eye. Visual acuity remained 20/20 in the left eye despite the presence of lesions likely due to the sparing of the fovea. Repeat OCT macula demonstrated reconstitution of the ellipsoid zone and improving hyperreflectivity of the outer nuclear layer (Figure 4). Repeat FAF showed decreasing hyper-autofluorescence (Figures 5A and 5B). With time, the lesions are expected to become hypoautofluorescent due to RPE atrophy. Repeat fundus photos after 2 weeks showed decreased retinal whitening and increased subretinal pigmentation within the area of the lesions in both eyes (Figures 5C and 5D).

TAKE-HOME POINTS

This case highlights that in a patient with suspected APMPPE, CNS vasculitis must be ruled out with imaging, and treatment with steroids can prevent long term vision loss. Although the prognosis is favorable, most patients will not achieve complete visual recovery. OM

REFERENCES

- Crawford CM, Igboeli O. A review of the inflammatory chorioretinopathies: the white dot syndromes. ISRN Inflamm. 2013;2013:783190.

- Jones NP. Acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy. British Journal of Ophthalmology 1995;79:384-389.

- Comu S, Verstraeten T, Rinkoff JS, Busis NA. Neurological manifestations of acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy. Stroke. 1996;27:996-1001.

- Holt WS, Regan CD, Trempe C. Acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1976;81:403-412.

- Testi I, Vermeirsch S, Pavesio C. Acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy (APMPPE). J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2021;11:31.

- Algahtani H, Alkhotani A, Shirah B. Neurological manifestations of acute posterior multifocal Placoid pigment Epitheliopathy. J Clin Neurol. 2016;12:460-467.

- Deutman AF, Oosterhuis JA, Boen-Tan TN, et al. Acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy. Pigment epitheliopathy of choriocapillaritis? Br J Ophthalmol. 1972;56:863-874.

- Van Buskirk EMLS, Frieman E. Pigment epitheliopathy and erythema nodosum. Arch Ophthalmol. 1971;85:369-372.

- Fiore T, Iaccheri B, Androudi S, Papadaki TG, Anzaar F, Brazitikos P, D’Amico DJ, Foster CS (2009) Acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy: outcome and visual prognosis. Retina. 29:994-1001.

- Pagliarini S, Piguet B, Ffytche TJ, Bird AC. Foveal involvement and lack of visual recovery in APMPPE associated with uncommon features. Eye (Lond). 1995;9 (Pt 1):42-47.

- Jones BE, Jampol LM, Yannuzzi LA, et al. Relentless placoid chorioretinitis: a new entity or an unusual variant of serpiginous chorioretinitis? Archives of Ophthalmology. 2000;118:931-938.