Refractive cataract surgery is an exciting and constantly evolving area in ophthalmology for both patients and ophthalmologists. Advances in technology have made it possible to offer many patients the possibility of spectacle independence after cataract surgery. Not surprisingly, patient expectations have also risen accordingly with many desiring excellent uncorrected vision after cataract surgery.

How do we then approach a patient with high-refractive expectations in the setting of a complex cornea? The first key to success is identifying that the patient has a cornea issue prior to surgery. It is not uncommon to see consults in which the cause for dissatisfaction after cataract surgery can be traced back to the cornea. When identified preoperatively, the cornea condition becomes a chance to educate the patient and to formulate a path to a successful 20/happy refractive outcome.

In this article, I will share my thoughts and methods that have helped me reach happy refractive cataract outcomes for my patients, and I will focus on conditions that seem to impact outcomes most commonly.

ANTERIOR BASEMENT MEMBRANE DYSTROPHY (ABMD)

ABMD is the most common corneal dystrophy. While severe ABMD can be seen easily, more subtle forms can be harder to catch. Even subtle ABMD, when centrally located, can impact refractive outcomes and cause poor quality vision that does not fully resolve with refraction.

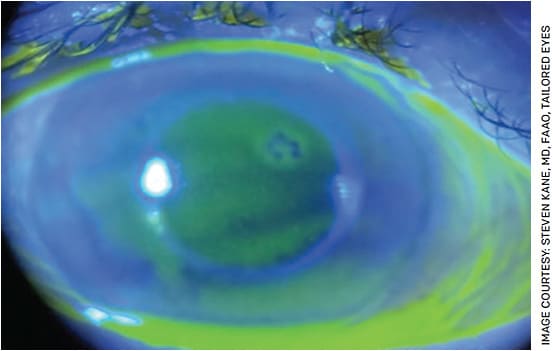

To help diagnose ABMD during cataract evaluation, I recommend staining all cataract evaluation patients with fluorescein, turning the slit lamp up as high as it will go and using a broad angled cobalt blue beam to focus on the corneal epithelium. In this setting, visually significant ABMD will appear as subtle dark lines pushing up through the sea of green fluorescein (Figure 1).

The challenging preoperative part for ABMD lies in deciding who needs to have it treated. My tip for success is to treat the ABMD prior to cataract surgery if it is significant enough to push above the tear film and is centrally or paracentrally located. While treatments vary based on surgeon preference, I have had excellent success treating visually significant ABMD with a superficial keratectomy and a cryopreserved amniotic membrane graft. After treatment, I wait a minimum of 3 months before proceeding with biometry. If there is any concern about reproducibility of the measurements or instability in refraction, then I will wait for corneal stability prior to proceeding. This is key, as some patients will continue to remodel the cornea long after the epithelium has healed. Once the cornea is smooth and stable, these patients can now have a successful refractive cataract surgery.

FUCHS’ ENDOTHELIAL CORNEAL DYSTROPHY (FECD)

FECD is another very common corneal dystrophy. Similar to ABMD, it is much easier to diagnose when the patient has severe disease than when there are only trace endothelial guttae present (Figure 2). Yet, even mild FECD can lead to patient dissatisfaction after cataract surgery. Often these patients will complain of glare or vision like they are looking through a veil. In addition, they can have prolonged corneal edema after cataract surgery.

To help diagnose FECD prior to cataract surgery, I angle the slit beam and focus on the endothelium just next to the light beam to pick up guttae in corneal retro-illumination. To help characterize the clinical severity of FECD, I recommend asking the patient about morning blurring of vision and how long it takes to clear. Another exam tip I recommend is to use the slit lamp to compare the patient’s peripheral corneal thickness to the central thickness. To do this, I use the highest intensity thin slit beam angled to the side and then pan across the cornea from the periphery through the center. If the light beam fails to get thinner, or worse, if it gets thicker as you move from the periphery across the corneal center, then this may indicate underlying thickening or edema.

I also offer Scheimpflug imaging of the cornea to help assess risk of disease progression after surgery as published by Patel et al, in Ophthalmology.1 In terms of surgical technique, I use dispersive viscoelastic and will inject a second coating in the anterior chamber after the first half of the nucleus is removed. When available, I recommend using a femtosecond laser to help reduce the amount of phacoemulsification energy needed to remove the cataract, which in theory may preserve more endothelial cells.

Treatment of astigmatism can be difficult in FECD patients as it may be irregular and tends to shift, especially after surgery. For FECD patients interested in refractive cataract surgery, they need a careful analysis of risk of progression coupled with a discussion about the durability of the treatment. For FECD patients at moderate risk of progression and above, I recommend treating the cornea with endothelial keratoplasty (EK) or Descemet’s stripping only (DSO).

One great refractive option for these patients is to offer combined cornea/cataract surgery with a Light Adjustable Lens (LAL), which can allow the cornea to stabilize prior to fine tuning the refractive outcome in the clinic. In practices where a LAL is not available, I recommend treating the cornea first with either EK or DSO and waiting until the cornea stabilizes prior to proceeding with a non-adjustable refractive cataract surgery implant.

POST-REFRACTIVE SURGERY PATIENTS

Post-refractive patients who desire refractive cataract surgery can present some of the most challenging patients to satisfy. Often, they are used to years of excellent vision without glasses and expect similar results after cataract surgery. I approach these patients with a discussion to help manage expectations.

I review the current biometry limitations related to accurately measuring the true corneal power and that the lens power may be off from the intended target 20-30% of the time. I spend extra time talking about this limitation with post-radial keratotomy (RK) patients. While they frequently have the most difficult irregular corneas to manage, RK patients have often struggled with poor quality vision for so long that they have more reasonable expectations of their vision after surgery (Figure 3).

For a standard or non-refractive RK cataract patient, I prefer to use the Envista IOL (Bausch + Lomb) as the aspheric optics give excellent quality vision for patients with irregular astigmatism. For all post-refractive patients, I recommend using a modern IOL calculation formula to be as accurate as possible. I have great success using a Lenstar biometer (Haag-Streit) with the Barrett True K formula for all my post-refractive calculations.

For practices that use other methods of biometry, such as the IOLMaster 700 (Zeiss), adding the total keratometry measurement to a modern formula may offer similar results. If using an older generation biometer, I recommend using the ASCRS post-refractive online calculator to determine the best lens power. For RK patients, I recommend a slightly more myopic target (often closer to -0.5 or -0.75) as they tend to drift toward hyperopia over time.

For post-refractive patients who want refractive cataract surgery, I discuss using an LAL. In these patients, an LAL minimizes the importance of preoperative biometry and helps maximize accuracy by fine-tuning the vision once the cornea stabilizes.

For RK patients who opt for an LAL, I wait at least 3 months or until I have a stable refraction prior to proceeding with lens power adjustment and lock in.

DRY EYE DISEASE (DED)

DED can also present significant challenges for successful refractive cataract surgery. Fluctuations in the tear film often lead to inaccurate K measurements and biometry. As the expression goes in the computer world, “Garbage in, garbage out.” Even after hitting the refractive target, some dry eye patients complain of fluctuating vision after surgery, which can take a long time to stabilize. Some dry eye patients don’t have eye irritation preoperatively, so it is important to educate them that dry eye often gets worse after surgery and they could experience discomfort postoperatively.

My approach to refractive cataract surgery in a dry eye patient is to optimize the corneal surface preoperatively. I recommend starting with a combination of preservative-free tears, oral dry eye supplements and warm compresses. If the patient is already on a dry eye regimen, then consider augmenting it with punctal occlusion, medications or meibomian gland treatments. Because dry eye treatments take time to work, I recommend bringing the patient back a few weeks later to reassess the ocular surface prior to proceeding.

CONCLUSION

Helping patients with complex corneas have a successful refractive cataract surgery starts with identifying and educating the patient about the problem ahead of time. I recommend spending extra time with these patients to make sure they understand their surgical course will be different from that of their peers who may have recently had straightforward cataract surgery. These patients often require additional visits or treatments to reach 20/happy, but they are also some of the most appreciative of the result, which is gratifying for the surgeon.

While many great treatment options are available today, these tips and pearls on refractive cataract surgery in patients with complex corneas represent my personal practice preferences. Hopefully my experiences can prove helpful to you in your practice too. OM

REFERENCE

- Patel SV, Hodge DO, Treichel EJ, Spiegel MR, Baratz KH. Predicting the prognosis of Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy by using Scheimpflug tomography. Ophthalmology. 2020;127:315-323.