Studies have shown that nearly 50% to 80% of patients presenting for cataract surgery can have signs and/or symptoms of dry eye disease (DED) on clinical examination and testing; however, nearly three-quarters of these patients are unaware that they have an underlying condition until informed by their clinician.1,2

A complete DED work-up to diagnose these patients can often seem overwhelming to a comprehensive ophthalmologist or a subspecialist not working in a dedicated dry eye center or treating dry eye on a daily basis. Similarly, the time and monetary investment needed to treat DED patients can be challenging. This is particularly difficult when we are faced with time-consuming prior authorizations to obtain prescription therapies, the patients’ inability to afford high co-pays or costs of in-office procedures, the need for multiple follow-ups and treatment trials for this chronic disease as well as the intolerance and/or length before patients notice an effect with immunomodulators. However, the diagnosis and treatment of DED doesn’t have to be a burden on you or your patients.

ELICITING DRY EYE SYMPTOMS

In my experience, sending patients a questionnaire prior to their evaluations — either via email or mail or having them fill out a questionnaire in the office while waiting to see the clinician — can be helpful in eliciting dry eye signs and symptoms. There are many available questionnaires, but the ones that I use in my practice include the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI), Standard Patient Evaluation of Eye Dryness Questionnaire (SPEED) and the Dry Eye Questionnaire (DEQ), as these surveys are quick for the patient to complete and straightforward for the provider to assess.

These questionnaires can be effective initial screening tools for office staff and providers before embarking on a more involved DED examination. Oftentimes, patients themselves do not know they have DED and will not vocalize that they are concerned about DED. However, when targeted questions are asked via a questionnaire as well as in person by technicians or the provider (ie, symptoms of eye pain, photosensitivity, tearing, foreign body sensation or transient blurring of vision), patients and clinicians can both come to realize swiftly that DED is a player if many of the answers are “yes.”

COSTS TO DIAGNOSE

Large dry eye practices may offer myriad diagnostics during their evaluation of DED along with a spectrum of therapeutics. The tests can include Schirmer testing, point-of-care testing such as tear osmolarity or matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) detection, topography, meibography, objective tear film break-up time and lipid tear film layer thicknesses, as well as cornea nerve imaging through confocal microscopy. However, many providers may initially be overwhelmed with the numerous diagnostic options for DED and may not have access to these testing adjuncts due to associated costs.

More simple and cost-effective approaches are available that can be implemented by providers who want to begin to more readily detect and treat DED.

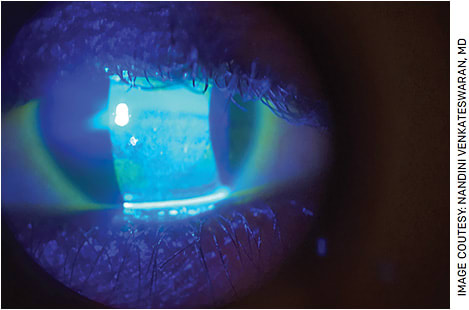

The most inexpensive yet powerful tool in the office to diagnose DED is the fluorescein strip. Placing a small drop of saline on the tip of a fluorescein strip and dabbing it in the inferior fornix can permit sufficient fluorescein to permeate the ocular surface and highlight irregularities on the ocular surface (Figure 1). Using pre-mixed fluorescein drops or topical anesthetic can flood the ocular surface with stain, adversely affect tear film stability and prevent detection of subtle surface pathologies. The clinician can readily determine tear break-up time, presence of corneal and conjunctival staining and height of the tear lake with a simple fluorescein strip. Lissamine green testing can also highlight abnormal ocular surface staining. Schirmer testing can also be an inexpensive test and is quickly performed by the technician or clinician and takes about 5 to 7 minutes.

FIGURE 1. Fluorescein staining highlighting significant keratopathy in a patient with DED.

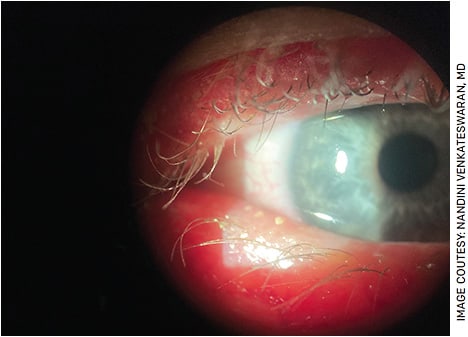

Evaluating the eyelids and meibomian gland architecture during the clinical examination is important as well. Assessing the lashes for debris, checking meibomian glands for adequate flow or inspissation with gentle pressure on the lid margins (Figure 2), assessing apposition of the lids to the globe or for the presence of floppy eyelids and everting the lids looking for foreign bodies or follicles can be done within 1 minute at the slit lamp and can provide a wealth of information. Presence of meibomian gland abnormalities or signs of conjunctivitis can highlight inciting factors for evaporative DED or other causes of ocular surface inflammation such as allergy.

FIGURE 2. Capped meibomian glands seen along the right lower eyelid clinically suggestive of significant meibomian gland dysfunction. This patient underwent thermal pulsation therapy in the office.

The combination of these simple examination measures can be implemented by any provider with minimal expense. It is also powerful to discuss these findings with patients and provide them with context as to why you feel DED has the potential to adversely affect their ocular health; this often leads to a better understanding and higher compliance with the suggested therapy.

If and when your DED patient population grows, you can consider investing in one or two technologies at a time, prioritizing those diagnostic tests that you feel will bring most value to your clinical practice and will be easiest to incorporate into your daily clinic flow. Elicit feedback from your technicians and counselors to see which technologies could work best in your clinic setting.

COMPLEXITY OF ATYPICAL SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

There is also a subset of patients who present with atypical DED signs and symptoms and can often go undiagnosed or misdiagnosed. Some patients come in with symptoms out of proportion to their clinical findings (often referred to as neuropathic dry eye), and others present with no symptoms despite extensive ocular surface breakdown (often considered neurotrophic cornea). These patients at times require more specialized testing as well as treatment options. For patients with a neurotrophic cornea, corneal sensitivity testing is critical, as diminished corneal sensation is a hallmark feature of this condition.

Educate your office staff that if patients are referred for diagnoses such as “dry eye, neurotrophic cornea, or herpetic keratitis,” it is best to avoid instilling an anesthetic drop in the eye prior to the clinician examining the patient in the event corneal sensation needs to be assessed. Any anesthetic placed in the eye will render corneal sensitivity testing inaccurate. However, in patients with neuropathic dry eye, the anesthetic drop challenge test can be very helpful. If a patient, after receiving a drop of anesthetic by the clinician, notes no improvement in eye pain symptoms, they likely have a manifestation of central nervous system sensitization, which has altered their pain pathways, leading to this discordance between lack of signs but persistent symptoms. Knowledge of these more uncommon entities can increase how often clinicians arrive at the correct diagnosis of DED.

A PLETHORA OF TREATMENT OPTIONS

While a subset of patients can be treated with just over-the-counter tears, ointments and lid hygiene therapies, others will require more intensive management. Treatment therapies can seem like a never-ending list for the general ophthalmologist, but knowing the range of options and identifying which ones are feasible for your practice to prescribe are important. Therapies to know about can include punctal occlusion, thermal pulsation or blepharoexfoliation of the eyelids, topical steroids or immunomodulatory therapy, autologous serum tears, topical recombinant human nerve growth factor (rhNGF) or even novel nasal sprays, scleral lenses or nerve-modulating agents.3

Speaking to other colleagues, reading the peer-reviewed literature, or using resources such as the Tear Film & Ocular Surface Society Dry Eye Workshop II (TFOS DEWS II) algorithm (bit.ly/2FzyfN8 ), the Cornea, External Disease and Refractive Society (CEDARS) algorithm (bit.ly/3KDMIVf ), or the ASCRS Preoperative OSD Algorithm (bit.ly/3ulRoJp ) can be helpful in understanding what tools to use to effectively diagnose and treat DED.

Ophthalmologists should attempt management with at least conservative therapies, such as over-the-counter tears, ointments and lid therapies, but be expedient in escalating to prescription therapies or in-office procedures when initial measures prove inadequate for the control of patients’ symptoms.

THE TAKEAWAYS:

- To begin more readily detecting and treating DED, you can implement simple approaches such as using a dry eye questionnaire, a fluorescein strip, Schirmer testing, and evaluating the eyelids and meibomian gland architecture. The combination of these simple examination measures can be implemented by any provider with minimal expense.

- Knowledge of more uncommon entities can increase how often you arrive at the correct diagnosis of DED.

- To better understand what tools to use to effectively diagnose and treat DED, talk to colleagues, read peer-reviewed literature or use dry eye algorithms.

- Ophthalmologists should attempt management with at least conservative therapies, but be expedient in escalating therapy when initial measures prove inadequate for control of patients’ symptoms.

CONCLUSION

Ultimately, the general ophthalmologist should always keep classic and atypical presentations of DED in the back of their minds when evaluating patients. A directed conversation with patients to elicit symptoms, a fluorescein strip to assess ocular surface staining and assessment of the patients’ eyelids and meibomian glands can be sufficient to diagnose the majority of cases. For more complex cases, collaboration with a dry eye or cornea specialist may be warranted; however, all ophthalmologists should feel equipped to do an initial screening and diagnosis of DED when needed. OM

REFERENCES

- Gupta PK, Drinkwater OJ, VanDusen KW, Brissette AR, Starr CE. Prevalence of ocular surface dysfunction in patients presenting for cataract surgery evaluation. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2018;44:1090-1096.

- Trattler WB, Majmudar PA, Donnenfeld ED, McDonald MB, Stonecipher KG, Goldberg DF. The Prospective Health Assessment of Cataract Patients’ Ocular Surface (PHACO) study: the effect of dry eye. Clin Ophthalmol. 2017;11:1423-1430. Published 2017 Aug 7.

- Mittal R, Patel S, Galor A. Alternative therapies for dry eye disease. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2021;32:348-361.