Bright eyed and bushy tailed, I graduated from residency in the tumultuous year of 2020. Less than 500 days later, I am already implanting newly available lenses during cataract surgery, using new drops for glaucoma and utilizing sustained-release drug delivery for my glaucoma and cataract patients. This is how fast the needle is moving in our beloved profession.

The Table shows a list of the most utilized sustained drug delivery systems available in the United States as of January 2022. As a cataract, refractive, cornea and glaucoma specialist, I have used Durysta (bimatoprost 10 µg, Allergan), Lacrisert (hydroxypropyl cellulose, Bausch + Lomb), Dextenza (dexamethasone 0.4 mg, Ocular Therapeutix) and Dexycu (dexamethasone 9%, EyePoint Pharmaceuticals).

| BRAND NAME | MEDICATION | COMPANY | APPROVAL YEAR | INDICATION(S) |

| Lacrisert | Hydroxypropyl cellulose | Bausch + Lomb | 2002 | Dry eye, exposure keratitis, neurotrophic keratitis or recurrent corneal erosions |

| Retisert | Fluocinolone acetonide 0.59 mg | Bausch + Lomb | 2005 | Chronic posterior uveitis |

| Ozurdex | Dexamethasone 0.7 mg | Allergan | 2014 | Macular edema following vein occlusion, posterior uveitis or diabetic macular edema |

| Iluvien | Fluocinolone acetonide 0.19 mg | Alimera Sciences | 2014 | Diabetic macular edema |

| Yutiq | Fluocinolone acetonide 0.18 mg | EyePoint Pharmaceuticals | 2018 | Chronic posterior uveitis |

| Dexycu | Dexamethasone 9% | EyePoint Pharmaceuticals | 2018 | Postoperative inflammation |

| Dextenza | Dexamethasone 0.4 mg | Ocular Therapeutix | 2018 | Postoperative pain following cataract surgery, allergic conjunctivitis |

| Durysta | Bimatoprost 10 mcg | Allergan | 2020 | Open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension |

| Susvimo | Ranibizumab | Genentech | 2021 | Neovascular macular degeneration |

But if all these innovations are available, why isn’t everyone using them? There’s no hard data on adoption at this point, but based on conversations with my peers, it is evident that a significant number are in no hurry. I tend to be an early adopter of new technologies and novel interventions, so this hesitation is perplexing to me.

I consulted my partner in practice, Bruce Saran, MD, for his perspective. My call with Dr. Saran was enlightening. An early adopter as well, he has utilized all the implants for posterior segment pathology, but he found that other physicians are often reluctant for three main reasons: cost, safety and comfort. I will explore those issues and offer my own tips for resolving them.

COST

Let’s start with the price of these new therapies. There is no question that millions, if not billions, of dollars go into the R&D, production, marketing and management of these products. The most efficient way to recoup these costs is to pass them on to the consumer — resulting in a high list price for each product. Fortunately, most of the companies have a robust patient access and reimbursement department that helps physicians and patients petition insurers to cover the products at affordable prices. In fact, many Medicare patients with a supplement can get these products for little to no cost, and even some commercial insurers have phenomenal coverage.

But here’s the problem: To ensure patient coverage, a significant amount of logistical work is required. I am fortunate to work in an office with a skilled billing department dedicated to prior authorizations and reimbursement. That is not the case everywhere, so some of the onus may fall onto the physician. However, all the manufacturers have patient-access divisions devoted to making the process efficient. For smaller practices, the best way to incorporate these technologies is to lean on the local sales representative to introduce practice staff to these accessible pathways to optimize efficiency and minimize hassle.

SAFETY

The next challenge: safety. We learn early in training that steroids can cause elevated IOP and cataracts. The posterior segment steroid implants —such as Yutiq (fluocinolone acetonide 0.18 mg, EyePoint Pharmaceuticals), Iluvien (fluocinolone acetonide 0.19 mg, Alimera Sciences), Ozurdex (dexamethasone 0.7 mg, Allergan) and Reticert (fluocinolone acetonide 0.59 mg, Bausch + Lomb) — are no different.

While some retina doctors work in a multispecialty practice with glaucoma specialists on hand, others do not. So, if an IOP spike occurs, who manages it? Additionally, most retina doctors in the United States do not routinely perform cataract surgery. While IOP spikes and cataracts are (typically) treatable, some retina specialists frankly do not want to deal with the hassle. Establishing a rapport with other specialists can allow for clear pathways for patient care if a complication should occur.

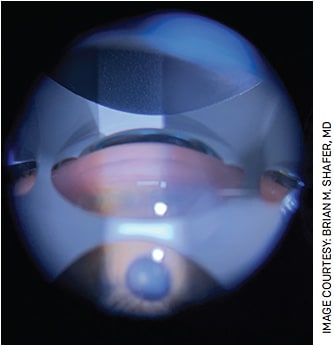

Speaking of IOP, Durysta is a first-in-class anterior chamber implant for the management of elevated IOP associated with ocular hypertension and open-angle glaucoma. As a new treatment paradigm, I find the glaucoma community has many mixed thoughts as well as mixed experiences. After more than 100 implants of Durysta, I have seen extremely favorable results with consistent IOP reduction and minimal adverse events.

While this is the experience of many ophthalmologists, others talk about their fear of endothelial cell loss, iritis, endophthalmitis and IOP spikes. We all took an oath to do no harm, and therefore safety is critical. Evaluating the adverse events of the clinical trial data is essential, and proceeding with caution while keeping a closer eye than usual on early patients is an effective way to incorporate them in practice.

COMFORT

Patient comfort is key when it comes to successfully prescribing an intervention. I spoke with Giacomina Massaro-Giordano, MD, a world-class dry eye specialist at the Scheie Eye Institute in Philadelphia and one of my mentors. When I asked her why she uses Lacrisert but some of her colleagues do not, she confirmed that cost is a problem but added patient comfort as a major obstacle.

Placing Lacrisert into the inferior fornix is a rather cumbersome process, and some patients are overwhelmed with application and the volume of lubrication. Dr. Massaro-Giordano reported she actually has some patients cut the insert in half to make it more manageable. Additionally, she says some eye-care providers have removed the therapy from their toolkit because of how much chair time it can require.

To circumvent this issue, providing patients with informational videos can help manage expectations and preemptively answer questions. These videos are readily available for all these products via manufacturer websites.

Physician comfort is an obstacle, too. For the past decade, anti-VEGF injections have been the mainstay of treatment for diabetic macular edema or cystoid macular edema caused by a vein occlusion. Switching to a long-acting steroid implant is certainly a paradigm shift and may put some specialists out of their comfort zones. While most glaucoma specialists are comfortable with prostaglandin analogues and selective laser trabeculoplasty, few are yet comfortable with sustained drug delivery for glaucoma. There simply has not been enough time, but that comfort level should increase over time.

When I entered medicine, the anti-VEGF revolution had already largely replaced first-line lasers with injections. Early adopters began injecting as soon as the interventions were available, but Dr. Saran notes that it was five or more years before other retinal specialists were satisfied that the science was clear enough for them to start.

MORE FREEDOM ON THE HORIZON?

I believe we are at a similar time point in glaucoma. Glaucoma drops are toxic to the ocular surface, and compliance is poor. Right now, we are on generation one of drug delivery with Durysta. But imagine once we have approval for repeat administrations of glaucoma implants and more medicines that can be placed in an implant. I can envision a world in which glaucoma patients present to the office every 6 months for their replacement implant that keeps them drop free for half a year.

I will welcome that paradigm.

Freedom from drops after cataract surgery is one of the many holy grails in our field. Currently, I use intracameral steroid, antibiotics and NSAIDs at the time of surgery and instruct patients to use a similar combination drop once daily for 1 month. Could I go drop free if I used more Dextenza or Dexycu? It’s possible, but what about the antibiotic? These questions are yet to be answered, but pushing innovation forward will only bring us closer to our goal.

The pipeline for drug delivery in ophthalmology is enormous. Rings, contact lenses, canalicular inserts, intracameral implants and intravitreal implants are all being developed for our most common, and some of our rarest, ophthalmic conditions.

This is the wave of the future. Will you be proactive in overcoming the obstacles to their use? OM