Take-Home Points:

- Early detection is key. Diagnosing AK while it is still localized to the epithelium or anterior stroma is critical to rapid resolution with minimal tissue destruction.

- AK is often misdiagnosed as HSV) Varicella-zoster virus keratitis. Keep Acanthamoeba on the radar when there is painful dendritiform keratitis in a contact lens user.

- AK can be diagnosed with corneal scrape and culture, polymerase chain reaction or confocal microscopy. Confocal microscopy can help detect cysts in earlier stages of the disease when amoeba density is low.

- Conventional treatment includes mono- or dual-topical therapy with a biguanide [PHMB 0.02%, chorhexidine, or the recently approved polyhexanide 0.08% (Akantior, SIFI] with or without a diamidine (propamidine, hexamidine).

- Oral miltefosine may be beneficial, though its use in advanced AK may be associated with corneal inflammation and progressive keratolysis.

- The role of topical steroids remains controversial. We use them rarely when damage from inflammation clearly outweighs that from infection.

Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK) is one of the more challenging corneal ulcers to treat. It can be difficult to diagnose, especially in its early stages, and it is notoriously resistant to currently available treatment options. Advanced disease is often associated with poor visual outcomes.

In this article, we will review the pathogenesis and highlight pearls for the diagnosis and management of AK.

UNDERSTANDING ACANTHAMOEBA

Acanthamoeba is a genus of free-living protozoa present in fresh water, soil, dust and air. They may exist as an infective, vegetative, motile trophozoite or as a dormant, resilient, double-walled cyst.1,2 Trophozoites typically have a size of 25-40 um and feed on bacteria, algae and yeasts. Double-walled cysts range from 13-20 um and are infamously resistant to antibiotics, freezing temperatures, desiccation, UV-light, gamma radiation and commercial chlorine levels.3,4

In the cornea, initial Acanthamoeba epithelial adhesion is mediated by a mannose-binding protein. Following epithelial adhesion, secretion of mannose-induced Acanthamoeba cytopathic protein (MIP-133) and various cytotoxic metalloproteinases results in deeper stromal invasion of Acanthamoeba.3

AK RISK FACTORS AND PRESENTATION

AK accounts for approximately 5% of microbial corneal ulcers.4 Contact lens (CL) wear is the leading risk factor, with up to 90% of AK occurring in the context of CL use or abuse (eg, swimming or showering in CL or rinsing CL in homemade saline).3 Other risk factors include trauma and exposure to soil or contaminated water.2-5

Patients often present with decreased vision and severe ocular pain characterized as “pain out of proportion to exam,” photophobia and epiphora.

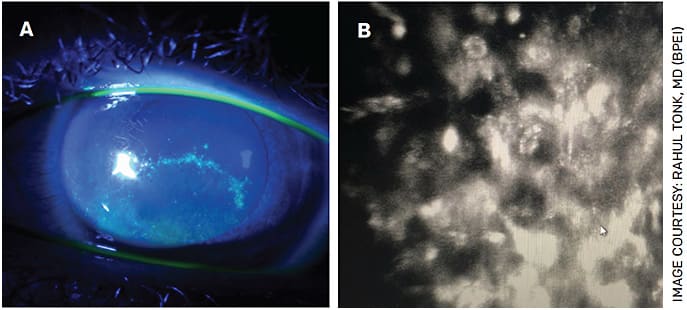

On examination, Acanthamoeba progresses from epithelial to stromal disease. Early in the course, patients present with punctate keratitis, epithelial pseudodendrites, web-like radial perineuritis, limbitis and epithelial loss (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Fluorescein slit lamp photograph of a patient with a pseudodendrite initially diagnosed as HSV keratitis (A). After limited response to HSV treatment, confocal microscopy revealed the presence of Acanthamoeba cysts (B).

These features lead to a misdiagnosis of Herpes simplex virus (HSV) or Varicella-zoster virus keratitis in up to 40% of patients.6 As a result, we routinely consider Acanthamoeba when diagnosing viral keratitis in a CL user.

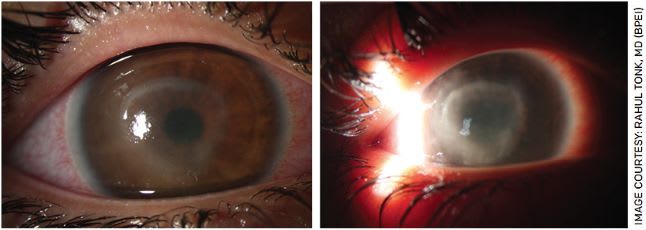

Later in the course of AK, patients may present with a ring-like infiltrate of inflammatory cells in the stroma (Figure 2) and/or with anterior uveitis or hypopyon. Though an immune ring is highly suggestive of Acanthamoeba, only about 50% typically present with this finding.1-6 In our experience, the presence of a ring infiltrate suggests deep parasitic infiltration and portends a worse prognosis.

FIGURE 2. Slit lamp photographs of Acanthamoeba keratitis demonstrating ring infiltrate. The image to the right shows the disease a little further along.

Other conditions on the differential include fungal or bacterial keratitis. In contrast to Acanthamoeba, fungal infiltrates have feathery borders with satellite lesions, and bacterial keratitis infiltrates are typically monofocal. Nevertheless, co-infection may occur in 8% to 23% of Acanthamoeba cases.1,2 Conversely, it is important to consider AK in CL users who have had positive cultures for another organism and are not improving as expected.

ACANTHAMOEBA KERATITIS: DIAGNOSIS

Corneal culture with direct detection is considered the gold standard for diagnosis of AK. Corneal scrapes should be stained with Gram, Giemsa, PAS, calcofluor white and acridine orange. Silver stain is particularly useful for the detection of cysts. Cultures should be obtained on non-nutrient agar with an E. Coli overlay.2 DNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR), when available, can greatly increase diagnostic sensitivity.7

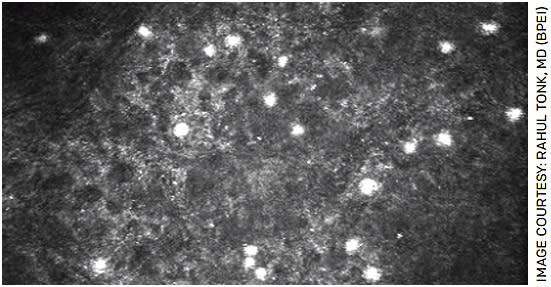

In vivo confocal microscopy (IVCM) is valuable, particularly in earlier stages of disease where amoeba density may be low. A positive IVCM involves the detection of double-walled cysts, signet rings and round/oval hyperreflective spots ranging between 12-20 um (Figure 3).8 Trophozoites, by contrast, are difficult to distinguish from other cell types.2,8 IVCM can require specialized technical and clinical skills to capture and review, thus cyst detection can vary.

FIGURE 3. In vivo confocal microscopy showing clusters of Acanthamoeba cysts in the corneal epithelium

One study from the Bristol Eye Hospital found conventional corneal culture, PCR testing and IVCM to have a sensitivity of 33%, 71% and 89%, respectively, as well as a specificity of 100%.8

Depending on the clinical course, more than one diagnostic method may be necessary to achieve a prompt diagnosis.

AK MANAGEMENT

Acanthamoeba does not respond to common antibiotics. Indicated biguanides and diamidines must be made in specialty compounding pharmacies or acquired abroad. Two classes of medications are generally employed in the treatment of Acanthamoeba: biguanides (polyhexamethylene biguanide [PHMB] or chlorhexidine) and diamidines (propamidine or hexamidine). While trophozoites are usually responsive to therapy, dormant cysts with their proteoglycan coat may be resistant.1-4

Presently available biguanides, or cationic antiseptics, include PHMB 0.02% and chlorhexidine digluconate 0.02%. These agents are not FDA approved for AK and are typically made by regional 503A compounding pharmacies. O’Brien Pharmacy (obrienrx.com ) is one such pharmacy that ships nationwide. (We use our in-house compounding pharmacy at BPEI.) Both PHMB and chlorhexidine are effective against trophozoites and cysts, especially in earlier disease.1-5,10

Polyhexanide 0.08% (Akantior, SIFI) is a commercial version of PHMB with a higher concentration than is typically made by compounding pharmacies. It recently received orphan drug designation from the FDA following a multicenter Phase 3 trial.11 This drug will soon be marketed in the United States and abroad.

A second class of medications are the diamidines, which include propamidine isethionate (0.1%) (Brolene, Sanofi) and hexamidine isethionate 0.1% (Desmodine, Bausch + Lomb). These medications are also not FDA approved for AK and are difficult to find in the United States, though they are available as over-the-counter drops in Europe. While the diamidines are effective against trophozoites, they have minimal activity against cysts, thus their use should be supplemental to biguanides.1-5

In general, we recommend a biguanide as monotherapy or in combination with a diaminide (when available) for dual therapy.1-5 Topical drops should be administered every hour — day and night — for the first 3 days. Drops can be reduced to every 2 hours during the day for 3 days then tapered according to patient response.12 Duration of therapy depends on severity of disease. In epithelial-only disease, topical therapy for up to 4 weeks may be sufficient; however, in stromal disease, therapy may last from 2-6 months or more.12 When questioning the endpoint of therapy, repeat cultures and IVCM may be valuable.13

Other anti-amoebic medications have varying efficacy when used in combination with conventional therapy. Topical imidazoles, such as fluconazole and ketoconazole, may be effective in eliminating trophozoites.1,14 Topical neomycin, by contrast, has not demonstrated efficacy and may be counterproductive by promoting corneal toxicity and the development of both neomycin-resistant and temperature-sensitive mutants.1,14

Miltefosine (Impavido, Profounda Inc.), an oral drug best known for the treatment of leishmaniasis, received orphan drug designation for the treatment of AK in 2016. Few high-quality studies exist demonstrating its efficacy.9,15,16 One case series of miltefosine for refractory AK (n=15) demonstrated disease resolution in 11 eyes and pain improvement in eight eyes. Eleven eyes experienced worsening inflammation, which generally improved with topical steroids.16 In our own case series of refractory AK (n=6), only two eyes notably improved after initiating miltefosine. The other four eyes continued to deteriorate, three of which ultimately required a therapeutic keratoplasty.9

The use of topical steroids in AK remains controversial and is deserving of further study. Steroids may inhibit the innate immune system that has potent activity against trophozoites.1 On the other hand, steroids may prevent long-term corneal vascularization, decrease pain and hinder corneal inflammation.17

Rose bengal photodynamic antimicrobial therapy (RB-PDAT), an emerging therapy developed at our institution, involves photosensitizing the cornea with rose bengal and then applying a custom green diode light in a procedure akin to UV cross-linking. The ensuing biochemical reaction generates reactive oxygen species that result in cell inactivation and death and may also strengthen the cornea against keratolysis. In our pilot study, RB-PDAT was successful in clearing Acanthamoeba in eight of 10 eyes that would have otherwise undergone therapeutic keratoplasty (TPK) with a time to clinical resolution of 20-90 days.18

Finally, TPK can be considered as a last resort in truly refractory cases or those that have already perforated. Outcomes are generally poor in TPK with high rates of Acanthamoeba recurrence, glaucoma, early and late persistent epithelial defects and low graft survival.19,20

OUTCOMES

The most important factor affecting prognosis is the severity of disease at presentation. Worse visual outcomes are associated with stromal involvement, treatment initiation after 3 weeks of symptom onset and the need for TPK, all of which highlight the importance of prompt diagnosis.1,5,21,22

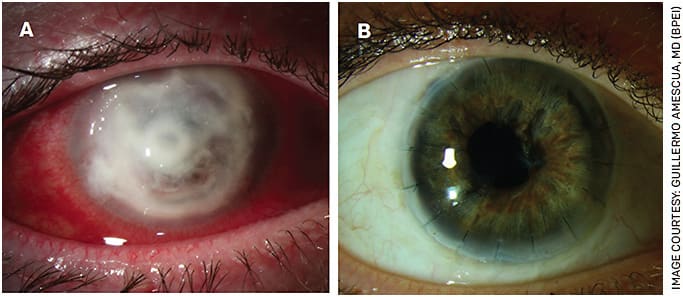

Following AK infection eradication, ocular surface inflammation and drop toxicity may give rise to limbal stem cell deficiency and persistent epithelial defects. Bandage contact lens, amniotic membrane, serum tears, punctal occlusion and tarsorraphies are options that may aid in epithelial healing.1 Long-term corneal sequela can include corneal scarring and irregular astigmatism (Figure 4). Visual rehabilitation may involve rigid gas permeable lenses, phototherapeutic keratectomy and keratoplasty (lamellar or penetrating) (Figure 5).1

FIGURE 4. Slit lamp photograph demonstrating central corneal scar after 7 months of topical dual therapy with PHMB and propamidine isethionate (0.1%) (Brolene, Sanofi) for Acanthamoeba keratitis

FIGURE 5. Slit lamp photograph of severe, refractory Acanthamoeba keratitis with a perforated cornea (A). This eye underwent a therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty. At last follow up (5 years after surgery), her visual acuity remains 20/25 (B).

CONCLUSION

Acanthamoeba keratitis, seen most frequently in CL wearers, is a vision-threatening disease that poses numerous diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Early recognition — aided by clinical suspicion, corneal culture, PCR and confocal microscopy — is essential to optimal outcomes. Medical and surgical treatment options continue to evolve. OM

REFERENCES

- Dart JK, Saw VP, Kilvington S. Acanthamoeba keratitis: diagnosis and treatment update 2009. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(4):487-499.e2.

- Lorenzo-Morales J, Khan NA, Walochnik J. An update on Acanthamoeba keratitis: diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment. Parasite. 2015;22:10.

- AAO Basic and Clinical Science Course. External Disease and Cornea. 2019-2020; Section 8:276-279.

- Szentmáry N, Daas L, Shi L, et al. Acanthamoeba keratitis - Clinical signs, differential diagnosis and treatment. J Curr Ophthalmol. 2018;31(1):16-23. Published 2018 Oct 19.

- Maycock NJ, Jayaswal R. Update on Acanthamoeba Keratitis: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Outcomes. Cornea. 2016;35(5):713-720.

- Shah YS, Stroh IG, Zafar S, et al. Delayed diagnoses of Acanthamoeba keratitis at a tertiary care medical centre. Acta Ophthalmol. 2021;99(8):916-921.

- Ikeda Y, Miyazaki D, Yakura K, et al. Assessment of real-time polymerase chain reaction detection of Acanthamoeba and prognosis determinants of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(6):1111-1119.

- Goh JWY, Harrison R, Hau S, Alexander CL, Tole DM, Avadhanam VS. Comparison of In Vivo Confocal Microscopy, PCR and Culture of Corneal Scrapes in the Diagnosis of Acanthamoeba Keratitis. Cornea. 2018;37(4):480-485.

- Naranjo A, Martinez JD, Miller D, Tonk R, Amescua G. Systemic Miltefosine as an Adjunct Treatment of Progressive Acanthamoeba Keratitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021;29(7-8):1576-1584.

- Lim N, Goh D, Bunce C, et al. Comparison of polyhexamethylene biguanide and chlorhexidine as monotherapy agents in the treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145(1):130-135.

- Acanthamoeba keratitis monotherapy meets endpoint in phase 3 study. Healio Ophthalmology. Published 2021. https://www.healio.com/news/ophthalmology/20211020/acanthamoeba-keratitis-monotherapy-meets-endpoint-in-phase-3-study . Accessed April 5, 2022.

- Seal D. Treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2003;1(2):205-208.

- Huang P, Tepelus T, Vickers LA, et al. Quantitative Analysis of Depth, Distribution, and Density of Cysts in Acanthamoeba Keratitis Using Confocal Microscopy. Cornea. 2017;36(8):927-932.

- Seal DV. Acanthamoeba keratitis update-incidence, molecular epidemiology and new drugs for treatment. Eye (Lond). 2003;17(8):893-905.

- Polat ZA, Obwaller A, Vural A, Walochnik J. Efficacy of miltefosine for topical treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis in Syrian hamsters. Parasitol Res. 2012;110(2):515-520.

- Thulasi P, Saeed HN, Rapuano CJ, et al. Oral Miltefosine as Salvage Therapy for Refractory Acanthamoeba Keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021;223:75-82.

- Carnt N, Robaei D, Watson SL, Minassian DC, Dart JK. The Impact of Topical Corticosteroids Used in Conjunction with Antiamoebic Therapy on the Outcome of Acanthamoeba Keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(5):984-990.

- Naranjo A, Arboleda A, Martinez JD, et al. Rose Bengal Photodynamic Antimicrobial Therapy for Patients With Progressive Infectious Keratitis: A Pilot Clinical Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;208:387-396.

- Kitzmann AS, Goins KM, Sutphin JE, Wagoner MD. Keratoplasty for treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(5):864-869.

- Kashiwabuchi RT, de Freitas D, Alvarenga LS, et al. Corneal graft survival after therapeutic keratoplasty for Acanthamoeba keratitis. Acta Ophthalmol. 2008;86(6):666-669.

- Chew HF, Yildiz EH, Hammersmith KM, et al. Clinical outcomes and prognostic factors associated with acanthamoeba keratitis. Cornea. 2011;30(4):435-441.

- Robaei D, Carnt N, Minassian DC, Dart JK. Therapeutic and optical keratoplasty in the management of Acanthamoeba keratitis: risk factors, outcomes, and summary of the literature. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(1):17-24.