It has been more than 20 years since corneal collagen cross-linking (CXL) was born in Europe and 6 years since the treatment for keratoconus received FDA approval. During this time, CXL has gained a strong and growing reputation as the most effective treatment for the disease that erodes the vision of 1 in 2,000 people in the United States each year.

Developed in Germany in the early 2000s, CXL takes about an hour and is performed using iLink (Glaukos), the only crosslinking system approved by the FDA. The system consists of an ultraviolet light source used in conjunction with two riboflavin formulations: Photrexa Viscous (riboflavin 5´-phosphate in 20% dextran ophthalmic solution) and Photrexa (riboflavin 5´-phosphate ophthalmic solution).

After a small portion of the epithelium is carefully removed by the surgeon, the drops are applied every 2 minutes for half an hour to saturate the underlying tissue. Ultraviolet light is then applied for about another 30 minutes to “cross-link” the underlying layers of collagen and strengthen the cornea.

“Crosslinking is pretty simple,” says John Hovanesian, MD, a cornea specialist with Harvard Eye Associates in Laguna Beach, Calif. The procedure, known as the “Dresden Protocol” or, more informally, the “epi-off” procedure, stops keratoconus progression permanently in nearly 100% of patients.

“In Europe, it is considered standard of care. In fact, it would be considered malpractice not to perform it on a patient with progressive keratoconus,” Dr. Hovanesian explains. “Here in the United States, that’s perhaps not quite true yet, but it is quite effective and is only getting better over time.”

PATIENT SELECTION

CXL indication

Keratoconus or ectasia can be hereditary or result from complications of LASIK or PRK procedures and other external factors such as eye rubbing. Patients with a familial history of keratoconus are more likely to develop the disease; a genetic test, AvaGen (Avellino), is available to score a patient’s risk for keratoconus from low to high.

“We use it particularly in family members of people with known keratoconus,” says Dr. Hovanesian. “If I’m 30 years old and I’ve got keratoconus, my nieces and nephews, my children are at certainly increased risk because there is some genetic predisposition.”

Armed with this knowledge, ophthalmologists can follow these patients more closely, performing more frequent exams and measuring the surface shape of the eye to help diagnose keratoconus and treat it with CXL at earlier stages, even before symptoms appear.

Crosslinking is FDA indicated for patients older than 14 with progressive keratoconus and a residual bed of no less than 400 μm of tissue after removal of the corneal epithelium. As noted on the AAO’s EyeWiki page (https://eyewiki.aao.org/Corneal_Collagen_Cross-Linking#Contraindications ), studies show that CXL is less effective in thinner corneas and corneal transplant is recommended instead. However, the FDA recommendations are not hard and fast, says Eric D. Donnenfeld, MD, with OCLI Vision in Garden City, N.Y.

“I routinely treat patients under 12, and I routinely treat patients with corneas less than 400 μm because the alternative is usually a corneal transplant,” says Dr. Donnenfeld, who was among three investigators in the clinical trials that led to FDA approval of iLink in 2016. “This is the best alternative we have, and I generally like to be more aggressive in treating patients with keratoconus who are younger, who have family histories, positive genetic testing and who rub their eyes.”

The 400-μm mark

“It becomes challenging when you have those patients who are approaching [400 μm],” says Eric D. Rosenberg, DO, a corneal specialist with SightMD, in Babylon, N.Y. “Maybe there’s some stability with their vision, but their vision is pretty poor at baseline, so what does stability really mean? And then, they’re coming to you for the first time, you don’t know how fast or slow it’s progressing and you don’t want to miss the window to cross-link those patients.”

In these cases, Drs. Rosenberg and Donnenfeld both rely initially on follow-up examinations ranging from every few weeks to every month or two. Significant changes in K-values or thinness of the cornea prompt Dr. Rosenberg to recommend CXL sooner than later.

Dr. Donnenfeld takes a similar approach, especially in younger patients with mild but actively progressing ectasia.“Once you lose vision from keratoconus, it doesn’t come back,” he says.

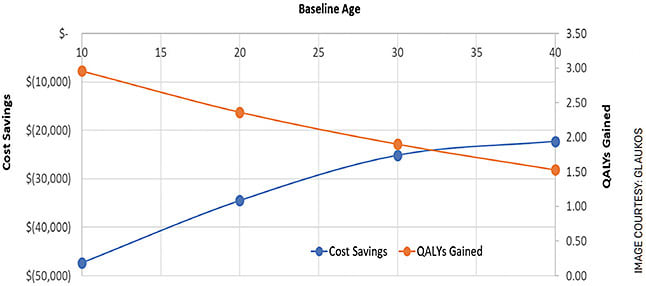

MODELING SUGGESTS COST EFFECTIVENESS OF CROSS-LINKING

BY JOHN BERDAHL, MD

In a study published last year in the Journal of Medical Economics, several colleagues and I used discrete-event microsimulation modeling to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of corneal collagen cross-linking as a treatment for progressive keratoconus. We simulated lifetime outcomes for both eyes of 2,000 individual patients, using data from the US multicenter Phase 3 pivotal trials that led to FDA approval of iLink (Glaukos) to define the characteristics of the preoperative population. In the model, treatment with iLink crosslinking resulted in a 26% reduction in the rate of penetrating keratoplasty (PK) and 28 fewer years spent in the advanced stages of keratoconus.

Directly related to these advantages: significant cost savings.

BENEFITS: SAVINGS PLUS

On average, patients saved $8,677 in direct costs — this translated to a national savings of between $150 million and $736 million when taking into account both direct costs and lost productivity. Many other indirect costs of advanced keratoconus, such as the impact on mental health or educational success, are not factored into the model. On the other hand, because we relied on relatively short-term data from the existing literature to build the model, the exact nature of long-term costs may be inaccurate in other ways.

Our model suggests that treatment conveys, on average, 1.88 additional quality adjusted life years (QALYs). Given that even one QALY in the United States is valued at $50,000 to $150,000 (according to the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review; https://tinyurl.com/yfdjrvk3 ) — far greater than the cost of the intervention — we can consider treatment to be highly cost-effective. When we varied the baseline age for scenario analyses, the modeling showed that intervention at a younger age maximized both cost savings and QALYs gained for each individual patient (Figure).

FIGURE. Plotting the impact of age of intervention on cost savings and quality-adjusted life years demonstrates that crosslinking treatment at a younger age is more cost-effective.

MORE DATA, BETTER DECISIONS

To anyone who has seen the impact of both PK and cross-linking on patients, these findings are not surprising. But we also know that not every patient progresses to the point of needing a corneal transplant, so it’s important to understand the value of treatment in a resource-limited world. This modeling exercise provides important data to help understand where resources can be used most effectively — for our patients and for the health-care system. OM

PATIENT CONSULTATION

The talk

As with any ophthalmic treatment, standard operating procedure calls for a discussion of CXL risks and benefits with patients. Risks include infection, scar tissue and treatment failure, all of which can lead to the corneal transplants CXL is intended to avoid.

“I tell them there are two things that they should be concerned about with their keratoconus eyes,” says Dr. Donnenfeld. “Number one, stopping the progression of disease, and number two, seeing better. There’s only one treatment that stops progression of disease, and that’s cross-linking.”

COLLAGEN CROSSLINKING: THINKING OUTSIDE THE BOX

BY W. BARRY LEE, MD, FACS

Epithelial-off collagen crosslinking (CXL) received FDA approval for the treatment of progressive keratoconus and progressive corneal ectasia after refractive surgery in 2016.1,2 While the epi-off technique has long-term studies confirming its success at stabilizing or halting keratoconus/ectasia and reducing the number of keratoplasty surgeries for the disease, there are also disadvantages: the long treatment times and removing the epithelium. These have led to additional off-label treatment techniques and expanding off-label indications for various cornea conditions.

EPI-ON TECHNIQUES

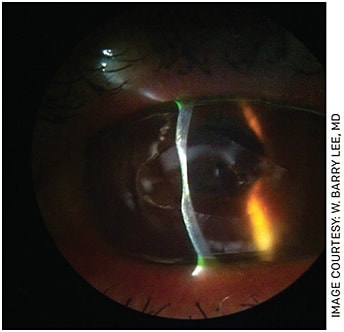

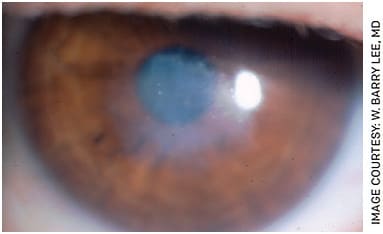

Because of the drawbacks of removing epithelium with epi-off CXL, epithelial sparing, or epi-on techniques, are under investigation in the United States. The numerous potential advantages include decreased discomfort and pain for the patient, a reduced risk of stromal haze and decreased risk of corneal infection (Figures 1 and 2).

FIGURE 1. Slit lamp photo showing marked keratolysis following delayed epithelial healing after epi-off crosslinking.

FIGURE 2. Slit lamp photo showing marked anterior stromal scarring after epi-off crosslinking in India.

While leaving the epithelium intact has theoretical advantages, it also leaves us with one concern — will the procedure be effective? Three components must be present within the cornea for treatment to take effect: riboflavin, UV light and oxygen. The epithelium may limit penetration of all three components into the stroma, thereby limiting the effect of the treatment.

Research shows that in-room air, oxygen within the corneal stroma depletes almost immediately once UV light treatment begins. This discovery led to the investigation of using supplemental oxygen pulsed at the time of treatment. Without adding any supplemental oxygen, even with epi-off treatment, the oxygen concentration within the stroma dropped to anaerobic levels upon initiating treatment.

On the other hand, upon initiating treatment in a hyperoxic environment, the stromal oxygen level remained above the level it was when in-room air prior to starting treatment. This may indicate that the stroma may remain adequately oxygenated for aerobic treatment when supplemental oxygen is used.3,4

Additionally, accelerated protocols using higher UV fluence ranges are also being studied in hopes of shortening the length of treatment — currently it’s one hour with the Dresden protocol.

CROSSLINKING AFTER RK

Crosslinking after radial keratotomy (RK) may be performed for corneal ectasia resulting from the corneal incisions or to improve refractive stability. The former may be covered by insurance since postrefractive surgery corneal ectasia is FDA-approved. However, CXL performed for the goal of stopping the constant vision and refractive instability of RK patients is off-label. The rapid instability of vision in RK patients can result in as much as several diopters of refractive shift throughout a single day, especially when patients travel to various altitudes. The remodeling of collagen that occurs with CXL is thought to potentially play a role in helping provide improved vision stability and improved refractive stability over time.3,4

CROSSLINKING FOR INFECTIOUS KERATITIS

Crosslinking to treat infectious keratitis remains controversial. While some studies have shown benefit, others show detrimental effects for crosslinking eyes with corneal ulcers from microbial infection. The UV light has been found to be toxic to microbes such as fungal and parasitic infections.

One concern with the treatment is making sure there is no component of Herpes simplex keratitis, as UV light is a trigger for virus flare in the cornea. If a herpetic ulcer is crosslinked, a high risk of corneal perforation develops, so the clinician must be sure of the pathogen if treatment with UV light is being considered. Crosslinking to treat corneal infections is off-label and not covered by insurance.

SELECTIVE CROSSLINKING

Selectively performing CXL in conditions such as Terrien’s marginal degeneration or pellucid marginal degeneration would enable treatment to specific regions of the diseased cornea while leaving the normal portions untreated.

These selective crosslinking treatments are used internationally but are yet to be FDA-approved in the United States.

In the future, we will likely have access to crosslinking that is effective yet avoids the side effects of epithelial removal. Treatment times will be reduced with higher UV light fluences and oxygen pulsation ongoing during the UV light exposure. Selective treatment will likely also be an option for asymmetrical abnormal corneas in need of collagen crosslinking for stabilization. OM

REFERENCES

- Wollensak G, Spoerl E, Seiler T. Riboflavin/ultraviolet-A–induced collagen crosslinking for the treatment of keratoconus. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135:620-627.

- Beckman KA, Gupta PK, Farid M, Berdahl JP, et al, the ASCRS Cornea Clinical Committee. Corneal crosslinking: Current protocols and clinical approach. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2019;45:1670-1679. https://tinyurl.com/2e9uumur . Accessed May 10, 2022.

- Kamaev P, Friedman MD, Sherr E, Muller D. Photochemical kinetics of corneal cross-linking with riboflavin. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:2360-2367.

- Beshtawi IM, O’Donnell C, Radhakrishnan H. Biomechanical properties of corneal tissue after ultraviolet-A–riboflavin crosslinking. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2013;39:451-462.

Patient concerns and comfort levels

Despite CXL’s proven success, some patients choose more conservative measures, primarily out of fear.

“Everybody has their own … comfort levels. That’s why it comes down to the discussion, especially in an area [of ophthalmology treatment] that isn’t as clear cut as maybe some other pathologies,” says Dr. Rosenberg.

But given the potential consequences of keratoconus, especially for patients with swift progression, he approaches the conversation with a careful explanation of the disease and potential for more drastic measures down the road, such as corneal transplant, while remaining sympathetic to their fears.

“I just had a patient the other day who got some plastic … embedded on the cornea. She wanted to be put under general anesthesia to remove it,” he says. “I try to put myself in their shoes, [but] I tell them that this is what I would do with my own eyes.

“I have no problem waiting and I have no problem doing crosslinking earlier rather than later,” Dr. Rosenberg adds. “I want them to be comfortable with the decisions they make because there are still risks associated with doing procedures, including haze and scarring. There’s even the possibility it doesn’t work.”

Affordability issues

Despite FDA approval, CXL remains out of reach for those who either don’t have health insurance or whose plans do not cover the procedure.

“Reimbursement is still very tricky,” says Dr. Hovanesian. “It is considered by some plans a covered service because it is FDA approved and recognized to have benefits for some patients, but it’s very spotty.”

To be sure, the list of insurers who cover CXL is growing. However, many limit coverage to their most expensive, top-tier plans. According to Dr. Rosenberg, the cost of CXL treatment, which requires Glaukos’ patented iLink system, can reach as high as $15,000. In addition, he says, some insurers still consider CXL to be an experimental treatment. As a result, he estimates, only two of every 10 of his patients who qualify for CXL actually get the treatment.

“It can be a difficult discussion to have with the patient if their insurances don’t want to cover [CXL],” says Dr. Rosenberg. “It’s a significant chunk of change out of pocket for the procedure, especially when using the FDA-approved Avedro unit.”

The options for such patients are limited to INTACS corneal inlays (KeraVision) and topographic laser treatment. But these measures only improve vision; they cannot stop progression of the keratoconus (See “Visual rehabilitation options for keratoconus,” p. 34).

“The most important step in my estimation,” Dr. Donnenfeld says, “is to stop the disease from getting worse. Once you get worse, all these other modalities become more challenging and sometimes impossible.” In these cases, the only option left is a corneal transplant.

“It’s disheartening, especially for us clinicians, when we have a patient who we know is going to benefit significantly from CXL, and we’re stuck sitting on our hands because the insurance company comes back at us and says, ‘this is an experimental treatment,’ adds Dr. Rosenberg. “An experimental treatment is plucking out somebody’s eyeball and then re-suturing in the optic nerve. This procedure has been around for 20 years, so there’s nothing experimental about cross-linking.”

Until insurance coverage becomes more widespread, there is one bright spot. Glaukos offers practices free supplies of riboflavin and cross-linking cards for patients who cannot afford to pay for the procedure.

PEDIATRIC KERATOCONUS IN THE CXL ERA

BY GERALD W. ZAIDMAN, MD

Corneal crosslinking (CXL) is an appropriate and effective solution for some pediatric patients.

Corneal stability is dependent on the “cross-linkages” between its collagen fibers. Theo Seiler and his group first proposed CXL in 1998. By combining ultraviolet light with riboflavin and oxygen, they could strengthen the “linkages” decreasing the disease’s progression. In 2003, Wollensak crosslinked 23 adult eyes — progression stopped in 100%. In 2017, Hersh et al published research in Ophthalmology showing that CXL decreased the maximum keratometry and that only 6% of the treated eyes progressed.

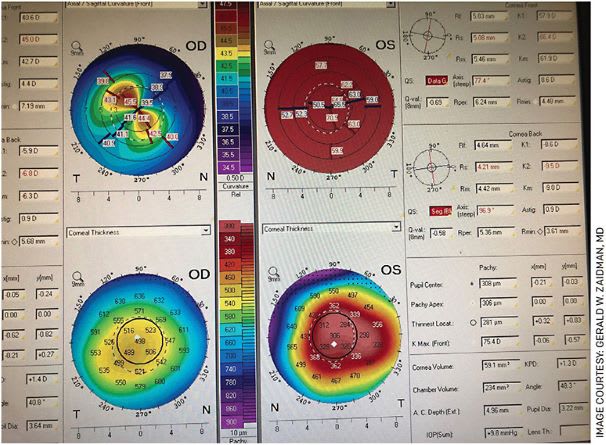

Topography of a child with bilateral keratoconus that is very severe in one eye

THE RESEARCH ON PEDIATRIC PATIENTS

In 2019 at the annual ASCRS meeting, my co-investigator and I presented a review of topographic findings in children referred for keratoconus. These children had at least 2 years of follow-up with frequent topography. We found three groups: Group A went on to a penetrating keratoplasty; Group B went on to crosslinking; and Group C did not require any treatment because these children did not progress.

Group A had an anterior mean keratometry (aKM) of 54.1 D, a posterior mean keratometry (pKM) of -8.14 D and a mean thinnest pachymetry (TP) of 416.7 μm. Group B presented with a mean aKM of 46.7 D, a mean pKM of -6.8 D and a meanTP of 470.8 μm. They had CXL, which halted the disease. Group C presented with an aKM of 45.3 D, a pKM of -6.7 D and a meanTP of 532 μm.

Our data suggested that children who presented with an aKM more than 54 D, a pKM more than -8 D and pachymetry less than 416 μm are at high risk for progression. All these children should undergo CXL. Additionally, children with aKM in the high 40s, a pKM more than -6.8 D and a pachymetry less than 480 μm will probably progress and should have CXL.

I have performed more than 60 transplants in children with keratoconus. Their average age was 16, 85% had bilateral disease and five had bilateral transplants before age 18. Approximately one-quarter of patients presented with hydrops in one eye. The mean KM of the patients who required surgery was 53.3 D, ranging from 42.9 D to 79.1 D. The mean KM value for the patients who did not require surgery was 49.2 D. Ninety-six percent of the patients had clear grafts. However, 50% of the patients had a graft rejection episode. All but one cleared following treatment. BCVA in the eyes with clear grafts was 20/30. Therefore, the vast majority of pediatric patients with transplants for keratoconus do well. However, the graft rejection rate is 50%, though with treatment, more than 90% of the grafts remain clear.

In 2018, Mazzotta, presented his 10-year results of pediatric CXL. He utilized the traditional epi-off treatment. After 10 years, 76% of eyes were stable, while 24% of the eyes progressed and required a retreatment. Only 3% of the patients needed corneal transplant surgery.

DATA-DRIVEN DECISIONS

Based on this data, what should we do for pediatric keratoconus? Here are my suggestions:

Any child older than 8 who has a family history of keratoconus or who has Down’s syndrome, Ehler-Danlos or severe eye rubbing should have corneal topography.

Any child with a best spectacle-corrected visual acuity less than 20/20 and has a scissors reflex or slit-lamp changes related to keratoconus and has >1 D increase in astigmatism or has >0.75 D increase in myopia should have topography.

When topography is done, we evaluate and monitor the aKM, pKM and TP.

If the child has an aKM more than 50 D, a posterior KM less than -8 D and pachymetry less than 440 μm, crosslinking should be performed.

Children who do not have these topographic findings should be monitored closely with topography every 4-8 months until we are sure they are stable. If progression occurs, then consider CXL.

In summary, by utilizing a combination of the family and ocular history, frequent clinical evaluations and topography and the guidelines presented above, we can decide which children are most appropriate for cross-linking. This will decrease their eventual need for corneal transplant surgery. OM

AN EVOLVING FOCUS OF R&D

‘Epi-on’ is on the horizon

Treatment for keratoconus remains an active subject of research and development. Among the approaches being studied is a variation of the epi-off procedure known, appropriately enough, as “epi-on.” Rather than being removed, the epithelium is left intact and riboflavin is added directly to the cornea to be absorbed. Like epi-off, the epi-on approach is used with the iLink system; it is in the midst of Phase 3 clinical trials.

Another company, CXL Ophthalmics, is trialing an epi-on solution of its own that consists of a combination of riboflavin and sodium iodide to enhance absorption and retention of riboflavin. And yet a new variation of iLink is in Phase 2 clinical trials. That version customizes the ultraviolet light for different areas of the cornea, which could potentially enhance post-procedure vision, says Dr. Hovanesian.

Physician innovations

The doctors themselves are also researching with their own modifications. Dr. Donnenfeld, for example, is using a technique in which he rubs the cornea with a sterile Q-tip to remove a portion of the epithelium. He says this approach allows the riboflavin to pass into the stroma to achieve high tissue levels “very effective” cross-linking.

“There is less pain, less infection and less risk of corneal scarring and other complications,” he explains. “That’s my little trick I use for patients who have keratoconus.”

Dr. Hovanesian, meanwhile, is employing iLink with a “compounded concentration” of riboflavin that penetrates the epithelium and is generating positive outcomes. “There’s a lot of data that supports it, and that it is a more patient-friendly way using currently FDA-approved machinery,” he says.

A “LIFE-CHANGING” PROCEDURE

Regardless of what the future holds, CXL represents a major advance in the treatment of keratoconus that has the potential to greatly limit the impact of the disease.

“If you don’t do cross-linking in your practice, you should have a relationship with somebody who does,” says Dr. Hovanesian. “It’s a truly valuable procedure that is life-changing for many patients. Whether you’re an optometrist or an ophthalmologist, you need to make this available to your patients in one way or another.” OM