Endophthalmitis is a complication every surgeon fears, especially in the setting of cataract surgery. A pivotal ESCRS study showed intracameral antibiotics decreased the rate of endophthalmitis by five-fold after cataract surgery.1 Similar results were repeated in other studies including in the United States.2

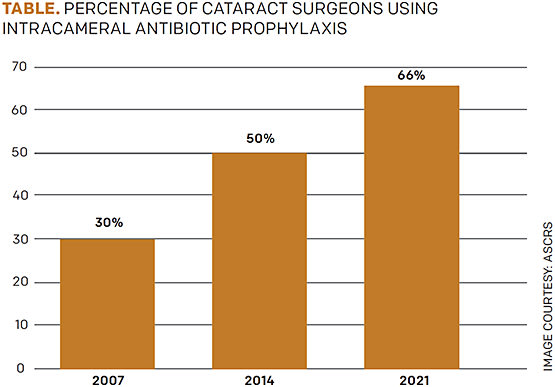

With multiple peer-reviewed studies showing the importance of intracameral antibiotics, one would assume this practice would have been adopted swiftly by all cataract surgeons. However, an ASCRS survey of its members showed only 30% utilization in 2007. That number rose to 66% in 2021, but it is still surprisingly low.

If intracameral antibiotic use has been shown to prevent devastating infection following cataract surgery, why hasn’t the practice been universally adopted? Hurdles for implementation in the United States include hesitation to use an off-label drug, fear of compounded medications, excessive cost and wastage of medications. The burden on the surgeon to prove the benefits outweigh the risks for the surgery center, which may still not agree to implementation.

This article reviews these challenges and offers suggestions on overcoming these hurdles to best care for patients.

LACK OF FDA-APPROVED DRUG

No FDA-approved intracameral antibiotic is available in the United States, and many surgery centers are hesitant to take the liability of using non-FDA approved antibiotics. The irony is most of the medications we use in ophthalmology are off-label use of an FDA-approved product, including nonsteroidal drops, antibiotic drops and anti-inflammatory drops. However, this adds an extra layer of liability in that the medication is administered in an off-label route as well — a topical eyedrop being injected in the eye. Medications are FDA approved for certain doses (eg, four times a day) and routes of delivery (eg, topical use) but can be used off label with different doses and different routes of delivery (eg, intracameral instead of topical). Though the standard is to use postoperative topical antibiotic eyedrops, they have been shown to be less effective than intracameral antibiotics; when combined they were not shown to be more beneficial than intracameral antibiotics alone.3

In a survey, ASCRS asked surgeons whether they would consider adopting a commercially approved intracameral antibiotic made available at a reasonable price, and the results showed that adoption would increase to 93%.4 So why can’t we just develop an FDA-approved drug? The FDA approval process for drugs is extremely rigorous and on average takes 12 years with the entire cost of a new approval being upwards of $1 billion.5

One solution could be a fast-track approval process. According to its website, the FDA can “facilitate development and expedite review of drugs to treat serious conditions and fulfill an unmet medical need,” and endophthalmitis could fall under this definition.6 However, it would be difficult for a company to justify the financial investment needed to put a new medication through the FDA approval process when it is already being widely used off-label. This results in a cycle in which the industry is not inclined to invest if development isn’t economically profitable; in addition, the FDA approval process takes so long that there is other lower hanging fruit that the industry can tackle first.

The FDA recognizes the broad use of moxifloxacin for intracameral use but has warned about its risks, noting 29 cases of toxic anterior segment syndrome (TASS), a lack of well-controlled studies that demonstrate moxifloxacin’s efficacy for treating endophthalmitis and no precisely established concentration or volume needed.7 The FDA mentions limitations such as higher than expected rates of endophthalmitis in the control group compared to European studies, the possibility of bias due to unmasked treatment groups and a large number of patients needed to treat for a benefit.8,9 They recommend that ophthalmologists know the intraocular moxifloxacin formulation and compounding mechanism, concentration and ingredients before they administer it.7 Considering the rarity of endophthalmitis, monitoring these parameters may represent an increase in the administrative burden on the surgery center and surgeons which could be mitigated by a standardized FDA approved version.

FIGURE. ASCRS survey of members regarding intracameral antibiotic use

COMPOUNDED MEDICATION CONCERNS

Compounded drugs are not FDA approved and there is inherent risk to using unregulated variations in concentration and formulation. One such case was reported in Dallas. Compounded triamcinolone-moxifloxacin was administered intracamerally during cataract surgery, and a contaminant (poloxamer 407) was found later that led to at least 43 patients experiencing adverse ocular effects, including significant visual impairment.10 There have also been a few cases of transient macular edema and anaphylaxis after patients were administered intracameral cefuroxime11 as well as an instance of incorrect dilution leaving eight eyes with permanent vision loss.12 Lastly with Moxeza (moxifloxacin hydrochloride) 0.5% from Alcon, there was an inactive ingredient of xanthan gum, which was linked to causing TASS and led to its current warning to only use it topically and not reconstitute it or compound it for intracameral use.7

Fortunately, an FDA-approved product is available in the United States: Vigamox (moxifloxacin) 0.5% from Alcon. It is utilized several ways, including out of the bottle, prepared through compounding pharmacies or diluted before injection. It is easy to use as it is already sterile, isotonic and contains no other potentially toxic preservatives. However, generic formulations are now appearing, and it is difficult to assess the safety of these products for intracameral use.

COST AND WASTE IN HOSPITAL SYSTEMS

Lastly, cost is an enormous issue in hospital systems. Major hospital systems are set up with rules that prevent use of one bottle of medication on multiple patients. Instead, one bottle is used per patient, after which what is left must be thrown away. As one can imagine, this is incredibly wasteful.

In a survey of cataract surgeons, more than 90% showed much support for using bottles of topical drops on multiple patients.13 Also, studies have shown that in addition to a decrease in endophthalmitis with intracameral moxifloxacin, there is no increase in rates of endophthalmitis when using a bottle of moxifloxacin on multiple patients.14

Hospitals need to look at the data and create standard operating procedures that allow for less waste in these cases. The system would be much better off allowing for physicians to use one bottle on multiple patients and even allow patients to keep what is left for postoperative topical application if prescribed. This would lead to improved outcomes for patients and an enormous cost savings for hospital systems.

At some US institutions, such as one our hospital surgery centers, the pharmacies are allowed to aliquot a medication per patient. Although extra work for the pharmacy, this allows medication to be dispensed in a less wasteful manner. This may be a temporary solution to allow surgeons access to intracameral antibiotics without cost and waste.

TURNING THE TABLE

Despite the clear peer-reviewed literature showing the importance of intracameral antibiotics, some surgery centers are still not adopting this protocol. It becomes the burden of the surgeon to advocate for the patient by bringing this data to the pharmacy committee. When a new drug is introduced, the company has a set slide deck for these approval committees, but off-label use drugs do not. We recommend surgeons bring the preferred practice patterns from the AAO15 and ASCRS4 as well as the data from the key pivotal trials to committee meetings as the resource for approval. We also recommend consideration of pharmacy aliquoting medication if the concern is sterility and hospital regulations.

CONCLUSION

The current standard of care, if based on the literature, shows that intracameral moxifloxacin is enormously beneficial to patients undergoing cataract surgery and leads to a significantly decreased risk of endophthalmitis. The European Medicines Agency approved intracameral cefuroxime in 2012, and the United States should not be lagging behind the world in this regard. However, we must first determine who determines the standard of care if not the literature — is it the surgeon, the hospital administration, the government? Using a medication in a way that saves eyes seems like an obvious path to take, but where the standard of care lies and how that fits in today’s practice is yet to be established. OM

REFERENCES

- Endophthalmitis Study Group, European Society of Cataract & Refractive Surgeons. Prophylaxis of postoperative endophthalmitis following cataract surgery: results of the ESCRS multicenter study and identification of risk factors. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007;33:978-988.

- Shorstein NH, Liu L, Carolan JA, Herrinton L. Endophthalmitis Prophylaxis Failures in Patients Injected With Intracameral Antibiotic During Cataract Surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021;227:166-172.

- Herrinton LJ, Shorstein NH, Paschal JF, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Cataract Surgery. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:287-294.

- Chang DF, Rhee DJ. Antibiotic prophylaxis of postoperative endophthalmitis after cataract surgery: results of the 2021 ASCRS member survey. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2022;48:3-7.

- Van Norman GA. Drugs, Devices, and the FDA: Part 1: An Overview of Approval Processes for Drugs. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2016;1(3):170-179. Published 2016 Apr 25.

- Fast Track, Breakthrough Therapy, Accelerated Approval, Priority Review. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/patients/fast-track-breakthrough-therapy-accelerated-approval-priority-review/fast-track . Published January 4, 2018. Accessed June 13, 2022.

- FDA alerts health care professionals of risks associated with intraocular use of compounded moxifloxacin. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-alerts-health-care-professionals-risks-associated-intraocular-use-compounded-moxifloxacin . Published August 12, 2020. Accessed June 13, 2022.

- Javitt JC. Intracameral Antibiotics Reduce the Risk of Endophthalmitis after Cataract Surgery: Does the Preponderance of the Evidence Mandate a Global Change in Practice?. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:226-231.

- Novack GD, Caspar JJ. Peri-Operative Intracameral Antibiotics: The Perfect Storm?. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2020;36:668-671.

- FDA’s investigation into Guardian’s compounded triamcinolone-moxifloxacin drug product. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/human-drug-compounding/fdas-investigation-guardians-compounded-triamcinolone-moxifloxacin-drug-product . Published July 5, 2018. Accessed June 13, 2022.

- Haripriya A, Chang DF. Intracameral antibiotics during cataract surgery: evidence and barriers. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2018;29:33-39.

- Olavi P. Ocular toxicity in cataract surgery because of inaccurate preparation and erroneous use of 50mg/ml intracameral cefuroxime. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012;90:e153-e154.

- Chang DF, Thiel CL; Ophthalmic Instrument Cleaning and Sterilization Task Force. Survey of cataract surgeons’ and nurses’ attitudes toward operating room waste. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2020;46:933-940.

- Haripriya A, Chang DF, Ravindran RD. Endophthalmitis Reduction with Intracameral Moxifloxacin Prophylaxis: Analysis of 600 000 Surgeries. Ophthalmology. 2017;124:768-775.

- Cataract in the Adult Eye PPP 2021. AAO. https://www.aao.org/preferred-practice-pattern/cataract-in-adult-eye-ppp-2021-in-press . Published January 7, 2022. Accessed June 13, 2022.