Our patient, a 41-year-old African-American female with a recent history of OD penetrating trauma complicated by vitreous hemorrhage who underwent pars plana vitrectomy and pars plana lensectomy, presented for a few days of acute onset OS vision loss and mild photophobia. She denied drug use, eye pain, flashes, floaters, fevers/chills, headaches, neck stiffness, hearing loss, flu-like symptoms or skin changes.

THE WORKUP

This patient had a history of penetrating injury with multiple eye surgeries presenting with vision loss in her fellow eye. Our differential diagnosis included sympathetic ophthalmia (SO), Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) syndrome, and bilateral granulomatous panuveitis/choroiditis (eg, sarcoidosis). Pertinent ocular examination findings and imaging results included the following:

- Distant visual acuity without correction:

- OD no light perception

- OS 20/100-2 (This had decreased from OS 20/20 prior to OD penetrating trauma & subsequent surgeries)

- Slit-lamp, indirect ophthalmoscopy and ocular diagnostic imaging:

- Conjunctiva: OD 3+ ciliary injection and diffusely chemotic; OS trace injection

- Cornea: OD opaque (phthisical appearance); OS mutton fat keratic precipitates on inferior corneal endothelium

- Anterior Chamber: OD unable to evaluate; OS trace cell

- Vitreous: OD unable to evaluate; OS trace cell

- Fundus: Cream-colored round choroidal lesions scattered throughout the macula and periphery (Dalen-Fuchs nodules) (Figure 1)

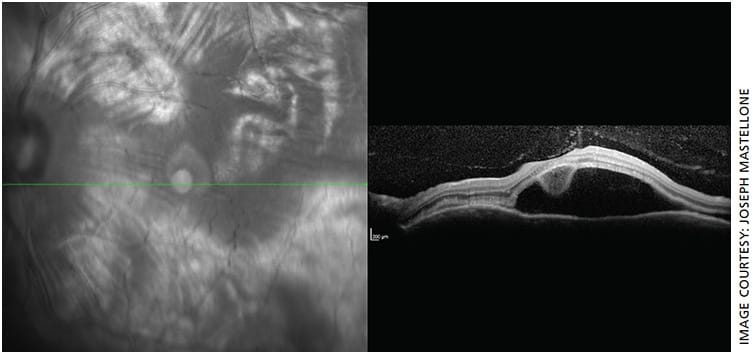

- OS macula OCT: Remarkable for large amount of subretinal fluid consistent with serous (exudative) retinal detachment (Figure 2)

- OS fluorescein angiography: Initial blocking defect of normal choroidal circulation inferiorly due to sub-retinal fluid, followed by early multiple stippled-pinpoint hyperfluorescence temporal to the macula with late pooling of fluorescein dye (Figure 3)

Our patient’s history, exam and diagnostic tests are highly characteristic of SO. She was admitted and followed daily for high-dose intravenous steroids, IOP checks and social work consultation.

DIAGNOSIS

SO is a rare, bilateral, necrotizing, granulomatous uveitis thought to be due to a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to uveal retinal pigment epithelial antigens (eg, melanocytes) that are released and exposed to T-cells following penetrating ocular trauma to the inciting eye with subsequent immune reaction that is most pronounced in the contralateral or fellow eye.1

Although many questions remain unanswered regarding the precise autoimmune pathophysiology of SO, bilateral intraocular inflammation arises within 12 months of the inciting event in 90% of SO patients2 but has been reported as many as 66 years later.3 Historically, the inciting event in the majority of SO cases is non-surgical (penetrating trauma) with the remainder coming from intraocular surgical interventions with scleral/uveal compromise (pars plana vitrectomy; intravitreal injection).4

Select patients may have a genetic predisposition to developing SO. One study found that British and Irish patients with HLA-DRB1*04-DQA1*03 genetic haplotypes were more likely to develop SO earlier following an inciting event, required fewer inciting ocular trauma events and were more likely to require intensive systemic steroid therapy to control inflammatory activity.5

Pathologically, the sympathizing eye demonstrates diffuse uveal tract (especially choroidal) thickening, sub-retinal fluid and/or exudative retinal detachment and Dalen-Fuchs nodules. Inflammatory responses are likely responsible for the uveal tract thinning, which recruits immunologic cells that accumulate underneath the retina and may cause detachment.

Dalen-Fuchs nodules are found between retinal pigment epithelium and Bruch’s membrane in approximately 33% of SO cases. They consist of epithelioid cells containing phagocytosed uveal pigment.6 Because SO closely resembles VKH, differentiating them is clinically relevant. SO spares the choriocapillaris, lacks systemic (neurological, cutaneous) symptoms and has a history of penetrating trauma.4

MANAGEMENT

Treatment of SO begins with careful management of the penetrating eye. Timely intervention within 3 to 6 months of the inciting event, with steroids, can help slow the destructive autoimmune responses driving SO and has been shown to maintain visual acuities of 20/50 or better in the sympathizing eye.7

Depending on level of SO suspicion or severity, patient compliance and follow-up capabilities, as well as other co-morbidities, the recommended regimen includes escalation of steroid potency from topical to periocular, subconjunctival or intravitreal steroids followed by systemic steroids. Cycloplegic drops, such as atropine or cyclopentolate, can help to prevent or treat the development of posterior synechiae. Internal medicine and/or rheumatology can be consulted for individualized, long-term systemic immunosuppression.8

Once SO develops, enucleation of the inciting eye is seldom performed, as this eye may turn out to be the better seeing eye of the two. However, if there is little to no vision remaining in the inciting eye, enucleation within 2 weeks of inciting event is recommended. In these cases, enucleation is preferred over evisceration to completely remove the inciting eye’s uveal antigens driving the hypersensitivity reaction.6

Given the increasing frequency of intraocular injections and retinal surgeries, providing appropriate counsel regarding the theoretical increased risk for this rare and sight-threatening entity remains an important aspect of obtaining informed consent.9,10

THE LESSON

Although rare, SO must be considered in patients with a history of penetrating trauma or surgery to the inciting eye and acute vision loss, pain, photophobia and/or loss of accommodation in the fellow eye. Obtaining a thorough review of systems, dilated ophthalmologic exam and appropriate diagnostic studies can help confirm the diagnosis.

Close follow-up in these patients with timely and aggressive topical steroid and systemic steroid and/or immunosuppressive treatment is necessary to help prevent progression to bilateral blindness. OM

REFERENCES

- Arevalo JF, Garcia RA, Al-Dhibi HA, Sanchez JG, Suarez-Tata L. Update on sympathetic ophthalmia. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2012;19:13-21.

- Goto H, Rao NA. Sympathetic ophthalmia and Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1990;30:279-285.

- Zaharia MA, Lamarche J, Laurin M. Sympathetic uveitis 66 years after injury. Can J Ophthalmol. 1984;19:240-243.

- Yanoff M, Sassani J. Ocular Pathology. 7th ed. 2015: Elsevier Inc. 1996:714.

- Kilmartin DJ, Wilson D, Liversidge J, et al. Immunogenetics and clinical phenotype of sympathetic ophthalmia in British and Irish patients. Br J Ophthalmol, 2001. 85:281-286.

- Vasconcelos-Santos DV, Rao NA. Sympathetic Ophthalmia In: Ryan’s Retina. 6th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1496-1504.

- Galor A, Davis JL, Flynn Jr HW, et al. Sympathetic ophthalmia: Incidence of ocular complications and vision loss in the sympathizing eye. Am J Ophthalmol, 2009. 148:704-710.e2.

- Cullom Jr RD, Chang B, editors. The Wills Eye Manual: Office and Emergency Room Diagnosis and Treatment of Eye Disease. Second edition. Lippincott-Raven Publishers:1994.

- Kilmartin DJ, Dick AD,Forrester JV. Sympathetic ophthalmia risk following vitrectomy: should we counsel patients? Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:448-449.

- Chu XK, Chan CC. Sympathetic ophthalmia: to the twenty-first century and beyond. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2013;3:49.