Dry eye disease (DED) is highly prevalent and can have a substantial impact on our patients’ eyesight and quality of life, so it’s important to diagnose and treat this condition early to avoid long-term consequences. These may include contact lens intolerance, increase risk of ocular infections and decrease in vision. Per the Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society Dry Eye Workshop II (TFOS DEWS II) report, DED is “a multifactorial disease of the ocular surface characterized by a loss of homeostasis of the tear film and accompanied by ocular symptoms in which tear film instability and hyperosmolarity, ocular surface inflammation and damage, and neurosensory abnormalities play etiological roles.”1

Although many types of DED exist, the two major classifications that form the continuum are evaporative dry eye (EDE), also known as meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD), and aqueous tear-deficient dry eye (ADDE). These two subtypes can be present individually or in combination, and they can influence each other.2

Diagnosing DED involves determining the type and severity of this disease to establish an appropriate treatment plan.

EDE VS. ADDE

EDE/MGD is thought to be the leading cause of DED (more than 85% of dry eye patients have MGD).1 MGD results in a deficiency in the lipid layer of the tear film, which leads to premature evaporation of tears. A poor quality or insufficient lipid layer may lead to tears evaporating four to 16 times faster than normal.

Aqueous deficiency dry eye (ADDE) occurs because of reduced aqueous production from the lacrimal glands. This results in a concentrated (hyperosmolar) and unstable tear film. Aqueous deficiency can be further separated into Sjögren’s syndrome-related and non-Sjögren’s syndrome-related. Only about 10% of DED is classified as strictly ADDE.3

TESTING ISSUES

Because no single reliable test to diagnose DED exists, clinicians rely on various ancillary diagnostics. These include fluorescein and lissamine staining of the cornea and conjunctiva, meibomian gland expressibility and imaging, Schirmer testing, tear breakup time (TBUT), matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9) and tear osmolarity. These all help to guide therapy. However, some tests are more specific to ADDE vs. EDE/MGD.

DIAGNOSING ADDE

Tests that may be performed to assess for ADDE include Schirmer’s test, tear height and tear turnover. Schirmer’s test with anesthesia is sometimes used to diagnose ADDE. A measurement less than 5 mm is consistent with low aqueous tear production.4 Schirmer’s testing has its limitations, and its results are often non-reproducible and inaccurate.

The tear meniscus, located at the junction of the bulbar conjunctiva and eyelid margins, reflects the overall tear volume — it is reduced in ADDE. The simplest method of measuring the tear meniscus is via the slit lamp; more advanced methods include OCT meniscometry and video meniscometry.4 Less than 0.2 mm is diagnostic.

DIAGNOSING EDE/MGD

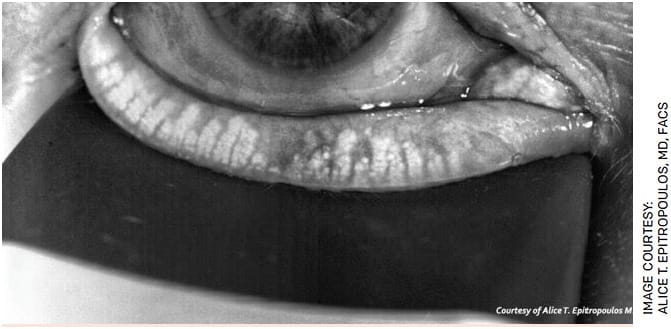

The clinical diagnosis of EDE/MGD is often made using a combination of subjective symptoms and clinical signs. Lid margin examination is more specific for EDE/MGD. Healthy meibomian glands should release a transparent liquid oil under gentle pressure to the lid margin, whereas thick or discolored meibum indicates gland dysfunction (Figure 1). During early development of MGD, patients may be asymptomatic. If asymptomatic, the diagnosis of EDE/MGD may be only detectable by the presence of clinical signs.

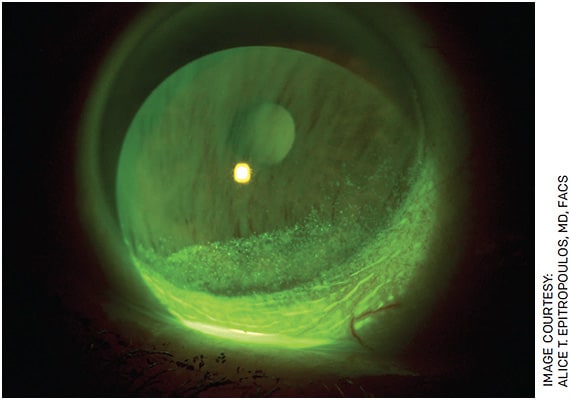

Meibography has revolutionized the diagnosis of MGD. This diagnostic tool allows for assessment of the meibomian gland morphology to determine whether the glands are damaged or atrophied (Figure 2). Meibography can provide information about the severity of MGD. The most common clinically observable signs of MGD include MG dropout, altered MG excretions and changes to the lid morphology with plugging or pouting of the MG orifice being the most pathognomonic sign of MGD.5

Furthermore, the measurement of tear film stability is fundamental to the diagnosis of evaporative DED. TBUT is the most frequently used diagnostic examination to assess tear film instability.5 A TBUT less than 10 seconds is considered abnormal.

THESE WORK FOR BOTH TYPES

Other tests are less specific and may be seen with either or both types of DED. These include corneal and conjunctival staining, increased evaporation and reduced tear film stability (Figure 3). Newer point-of-care testing, such as tear film osmolarity and tear film MMP9, provides useful and objective information but cannot differentiate between EDE and ADDE.

Tear osmolarity has been shown to have the highest correlation to DED severity. DEWS II states that tear osmolarity is the single best metric to diagnose and classify DED.4 A tear osmolarity greater than 308 mOsm/L or a difference of more than 8 mOsm/L between eyes is considered abnormal.4

THE FOUNDATION HASN’T CHANGED

Despite the point-of-care tests that we have available, the hallmark for an accurate diagnosis remains a good history and careful clinical exam.

Traditional diagnostics, such as TBUT, evaluating the lids and lid margins, quality of tear film and corneal/conjunctival staining, can help distinguish between aqueous deficient and evaporative DED and should be incorporated in every patient exam. OM

REFERENCES

- Craig JP, Nichols KK, Akpek EK, Caffery B, Dua HS, Joo CK, et al. TFOS DEWS II definition and classification report. Ocul Surf 2017;15:276-283.

- Lemp MA, Crews LA, Bron AJ, et al. Distribution of aqueous-deficient and evaporative dry eye in a clinic-based patient cohort: a retrospective study. Cornea 2012; 31:472-478.

- Messmer EM. The pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of dry eye disease. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112:71-81.

- Wolffsohn JS, Arita R, Chalmers R, et al. TFOS DEWS II diagnostic methodology report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15:539-574.

- Tomlinson A, Bron AJ, Korb DR, et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: report of the diagnosis subcommittee. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(4):2006-2049.