Dry eye disease (DED) represents a major public health problem, with over 15 million people diagnosed, and at least another 15 million who have not been formally diagnosed.1 The annual cost of treating DED in the U.S. alone is estimated to be $3.8 billion. Moreover, this condition has been shown to influence the outcome of cataract surgery, the most commonly performed surgical procedure in the U.S., because nearly 80% of patients presenting for a cataract evaluation have signs of DED.2

In this article, we will explore an approach to systematically evaluating DED patient symptoms and standardizing patient education to potentially guide better treatment.

What is This Approach?

The approach is psychometrics, or the study of psychological measurement, which includes attitudes and personality traits. In health care, hundreds of psychometric instruments (questionnaires) have been developed and validated. Validation is the process of rigorously evaluating an instrument for its consistency among different patients, its correlation with other signs of disease, and for its ability to stage the severity of disease.

In DED specifically, the two most commonly used patient-reported outcome instruments are the Standard Patient Evaluation of Eye Dryness (SPEED) questionnaire, and the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI.)3 Some practitioners routinely collect these from patients to determine severity of disease at presentation or to gauge improvement over time. That said, the breakdown of specific responses are not generally collected as structured data, nor analyzed for their correlation with clinical findings or treatment success. The reason: Experienced clinicians tend to develop biases from their own perception of what works rather than from rigorous patient feedback.

An ancient parable works as an analogy for this: Three blind men are told that a strange animal called an elephant has been brought in to their village. None of them is familiar with its shape and form. One feels the tail and describes the beast as a snake. Another feels its flank and describes it as like a wall. The third feels its tusk and describes it as a spear. The moral is that we all have a tendency to believe steadfastly in the truth that we have personally observed.

This parable is also a good analogy for the way we evaluate disease: The three blind men represent patient history, physical exam, and diagnostic testing. For us to get the most accurate understanding of disease, we cannot ignore any one of these three. To avoid bias, we must determine which historical features, exam findings, and diagnostic results predict treatment success for each available treatment modality. In other words, rather than treating complex conditions such as DED from the “seat of our pants,” we should follow a specific recipe guided by all three.

It is not difficult to rigorously classify exam findings and diagnostic testing results; grading scales exist for conjunctival redness, corneal staining, tear break-up time (TBUT) and other parameters. Diagnostics are objective and numeric by their nature. Patient history, on the other hand, is a little bit trickier.

Validated instruments represent one way to do this, but their primary purpose is not to guide treatment so much as to stage the severity of disease. For this reason, I founded MDbackline (www.mdbackline.com ), a web-based software that remotely administers condition-related questionnaires and aggregates thousands of patient responses into a database.

How Does the Approach Work?

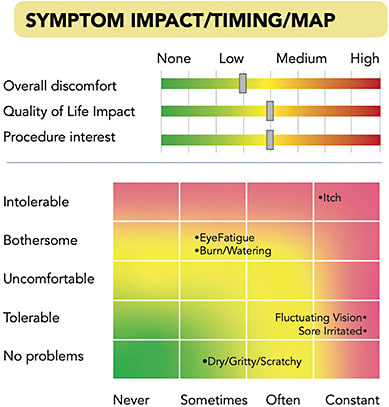

When a patient is scheduled for an appointment, MDbackline sends them an automated text message or email from the doctor with the doctor’s photo and a request to answer some questions electronically before the appointment. The patient then completes the online questions via smartphone, tablet, or computer, and views some learning material about, in this case, DED to prepare for treatments that might be recommended. The patient’s responses are displayed for the clinician in a one-page, color-coded Visual Profile Report that can be printed or viewed on a screen. The Visual Profile Report gives clinicians a quick view of the most important elements of patient history for the condition. Thus, the clinician can see how impactful DED is in the patient’s life and which symptoms are most significant (Figure 1). A symptom map depicts the severity of symptoms on one axis and frequency on another. At a glance, the most frequent and severe symptoms stand out in the red-shaded areas, while less significant symptoms appear in the lower left, green-shaded area. Slider bars depict overall discomfort, quality-of-life impact, and patient self-reported interest in DED in-office treatments.

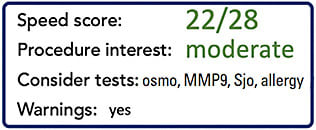

Other sections of the Visual Profile Report and the questionnaire itself address symptom timing, number of previous visits with a doctor, treatment cost, medical history, home treatments used, and other elements of history that are useful in addressing a patient’s needs. In the lower right of the Report is a summary that includes the patient’s SPEED score and also a prediction of the patient’s interest in undergoing in-office lid treatments (Figure 2). This visual profile report is intended to shorten the time required for history collection, while quickly identifying those who might best be served by an in-office DED treatment.

Why is Such an Approach Needed?

Treating DED is challenging, not only because the condition is chronic and requires ongoing intervention, but because different patients present with different clinical presentations, be it poor TBUT, ocular redness, or something else. Furthermore, environment and systemic medications, such as antihistamines, and conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis, can influence the nature of DED and may have implications for treatment choice: No single approach is likely to satisfy every patient.

Recently, the Tear Film & Ocular Surface Society (TFOS) developed its own algorithm, as has the Cornea, External Disease, and Refractive Society (CEDARS) group, and the ASCRS Cornea Clinical Committee. While these general guidelines help direct treatment, they are appropriately broad in their recommendations, given the variability of patient response and treatment options.

All treatment approaches depend, to some extent, on identifying whether the patient has meibomian gland dysfunction versus aqueous deficient DED, or some combination. DED diagnostic testing may further clarify the best treatment path, but these too have their limitations.

Symptoms play a role in DED treatment algorithms but only in very general terms. It is quite possible that a more rigorous look at symptoms could guide treatment with more specificity. This is where the psychometrics approach comes in.

Findings Thus Far

Over the past few years, MDbackline has been collecting questionnaires from patients who have already undergone evaluation in the office. The focus of this questionnaire is to determine patient satisfaction, which treatments are actually being used, and how well the patient thinks their treatments are working.

The findings from over 2500 patients have been interesting. Specifically, nearly 80% of patients report they are “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with their DED treatment, while fewer than 5% say they are “dissatisfied” or “very dissatisfied.”

With more time and more structured patient responses, and with a growing database of longitudinal data on individual patients, more patterns will emerge showing which treatments truly deliver value and in which scenarios.

Understanding the complexities of patient disease requires multiple sources of information. As with the physical exam and diagnostic testing, patient history can provide novel insight if we collect it rigorously and know how to interpret the responses. CP

References

- Schaumberg DA, Sullivan DA, Dana MR. Epidemiology of dry eye syndrome. Exp Med Biol. 2002;506(Pt B):989-98. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0717-8_140.

- Trattler WB, Majmudar PA, Donnenfeld ED, McDonald MB, Stonecipher KG, Goldberg DF. The prospective health assessment of cataract patients’ ocular surface (PHACO) study: the effect of dry eye. Clin Opthalmol. 2017;11:1423-1430.

- Grubbs JR, Tolleson-Rinehart S, Huynh K, Davis RM. A review of quality of life measures in dry eye questionnaires. Cornea. 2014;33(2):215-218.