Neurotrophic keratopathy (NK) occurs in the setting of decreased corneal sensitivity and can lead to the development of persistent epithelial defects, poor corneal healing, infection, and corneal scarring. The first-stage treatments for this rare, degenerative condition are artificial tears and ointment to maintain the health of the ocular surface. That said, disruption of the corneal innervation from the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve can lead to a cycle of decreased reflex tearing and an abnormal blink in NK, further damaging the corneal epithelial cells.1,2 When this occurs, surgical management may be required to assist in the protection of the ocular surface.

The surgical management of NK can be divided into techniques that optimize the ocular surface or cover the neurotrophic cornea with tissue; those that intentionally narrow the palpebral fissure to minimize the exposure of the neurotrophic cornea; and those that repair lid malposition but may contribute to the persistence of NK. Methods such as punctal occlusion,3 amniotic membrane transplantation4,5 and conjunctival flaps6 have been used to optimize the ocular surface.

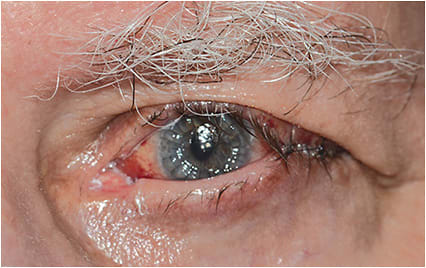

This article focuses on oculoplastic surgeries that may be used in lieu of, or in combination with, the techniques described. A caveat: Conditions such as lower lid ectropion, upper lid retraction, or lid laxity in the setting of a facial nerve palsy may lead to increased corneal exposure and abnormal distribution of tears across the ocular surface, contributing to poor corneal wound healing in the setting of NK (Figure 1). As a result, multiple surgical techniques are often required to achieve the goal of protecting the neurotrophic cornea. The oculoplastic surgeries are:

Temporary Suture Tarsorrhaphy

This simple procedure7,8 closes the lids over the neurotrophic cornea and may facilitate improvement or resolution of NK by limiting corneal exposure and minimizing the blink reflex, which can slow the ingrowth of denervated corneal epithelial cells.

In a patient with good vision in the contralateral eye, the eye should be closed for at least two-thirds of the length of the lids to cover the cornea, while allowing drops to be instilled medially, and the cornea to be examined in medial gaze. The procedure can be performed in the office under local anesthesia at the time of the initial consultation. Multiple, nonresorbable, monofilament sutures are placed partial thickness through the skin and orbicularis of each lid with the knots externalized, allowing the treating physician the option of cutting the sutures sequentially as NK improves (Figure 2). The disadvantages of this technique include limiting the visual field, making the examination of the cornea more challenging, and introducing the potential of suture material or lashes exacerbating corneal damage if not performed correctly.

Temporary suture tarsorrhaphy may also be used in preparation for cenegermin-bkbj (Oxervate, Dompé), a recently FDA-approved drop for NK that delivers human nerve growth factor (NGF) to the cornea. NGF acts on corneal epithelial cells to energize their growth and survival, according to Dompé. Further, it binds receptors on lacrimal glands, prompting tear production. Finally, NGF is shown, experimentally, to support corneal innervation, something lost in NK. While awaiting health insurance approval and delivery of this medication, the surgeon may utilize a suture tarsorrhaphy, along with topical lubrication, to support the neurotrophic cornea. Once Oxervate is obtained, the suture tarsorrhaphy may be released.

An alternative to a temporary suture tarsorrhaphy is the use of botulinum toxin in the levator palpebral muscle of the upper lid to induce ptosis, closing the lid over the neurotrophic cornea.9,10 This approach facilitates installation of any necessary drops and examination of the cornea. The disadvantages are it takes several days to take effect and provides limited protection against mechanical trauma to the cornea from eye rubbing.

Permanent Tarsorrhaphy

A “permanent” tarsorrhaphy creates scar tissue that closes the lids indefinitely, unless reversed by a second surgery.11,12 In cases of refractory NK, the procedure may be necessary to narrow the palpebral fissure for longer periods of time.

This technique differs from a suture tarsorrhaphy in that the surgeon removes the epithelial surface of the upper and lower lid margin for the desired length of closure and apposes the lids using resorbable vertical mattress sutures. This closure is then reinforced with monofilament sutures that are removed at 7 to 14 days. Permanent tarsorrhaphy can be done in a manner that spares the visual axis, using both lateral and medial tarsorrhaphies, or, in the case of refractory NK, can be extended for the entire length of the lids (Figure 3). In the event that NK improves, the tarsorrhaphy may be reversed in stages to ensure that the corneal epithelium does not break down following reversal. The disadvantages of permanent tarsorrhaphy include loss of a portion of the visual field and poor cosmetic outcome.

Upper Lid Weight Placement

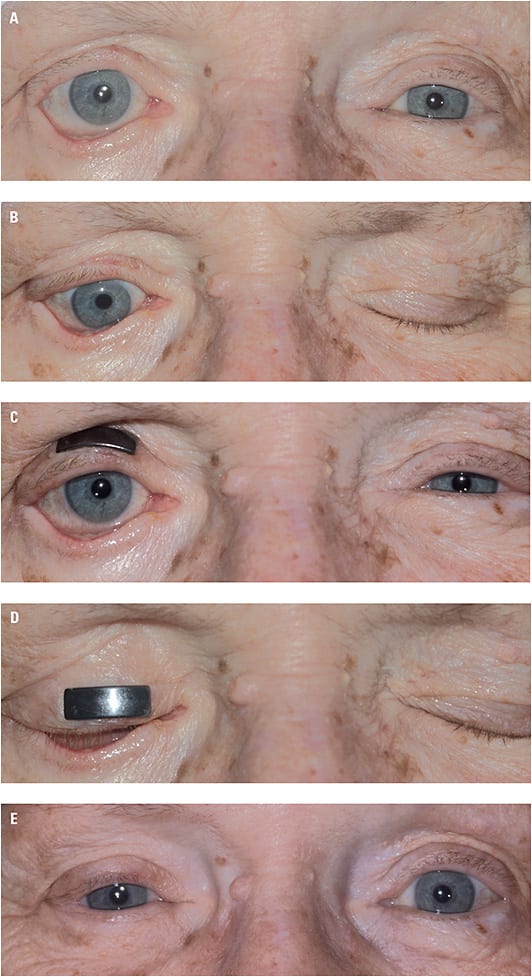

An upper lid weight may be placed to facilitate closure of the upper lid with initiation of a blink13,14 when NK occurs in the setting of a facial nerve palsy. The facial nerve palsy leads to upper lid retraction, an incomplete blink with lagophthalmos, and lower lid malposition, which may be compounded by a poor Bell’s response that creates constant exposure of the neurotrophic cornea (Figures 4a, 4b).

During an in-office consultation, test weights may be fixed to the upper lid with an adhesive strip to determine the optimal weight that achieves a more complete blink without leading to significant ptosis at baseline.15 (Figure 4c, 4d) The chosen weight, typically made of gold or platinum, is then fixed to the anterior surface of the tarsus with nonresorbable sutures via an anterior lid crease incision. Care should be taken to cover the entire implant with orbicularis to minimize the risk of implant extrusion over time. This surgery can be combined with a temporary or permanent tarsorrhaphy to further protect the neurotrophic cornea or lower lid repair to address any malposition. The disadvantages of this technique include the potential for postoperative ptosis, implant extrusion and the cosmetic implications of the weight in patients with pretarsal show.

Lower Lid Malposition Repair

Lower lid malposition can confound the healing of NK, due to increased exposure, irritation of the ocular surface, and poor distribution of the tear film. In the setting of refractory NK, one should consider the repair of any lower lid malposition, including entropion, ectropion, or lower lid retraction:

In cases of lid laxity or mild paralytic ectropion, a tarsal strip may be all that is required to achieve an optimal position of the lower lid margin. However, in cases of cicatricial scarring associated with lower lid ectropion, full-thickness skin grafting may be needed to achieve the desired goal.20 In cases of medial dehiscence of the lower lid attachments, a medial canthoplasty may be performed to restore the normal position of the lower lids.21 These techniques can be performed in conjunction with a temporary or permanent tarsorrhaphy, amniotic membrane, or a conjunctival flap to further protect the neurotrophic cornea (Figure 5).

Numerous surgical techniques have been developed to address lower lid retraction. Most include the use of a lower lid implant, in addition to lateral tightening (Figure 4e). The implant serves to provide vertical support to the denervated lower lid. Surgical approaches include both transconjunctival and transcutaneous incisions, with the goal of releasing the lower lid retractors and creating a pocket to fix the implant to the inferior tarsal border. Various types of implants have been utilized, including, but not limited to, autologous implants, such as hard palate, tarsus with conjunctiva, or postauricular cartilage allogenic implants, such as acellular tissue matrix; or donor sclera and alloplastic materials, such as porous polyethylene, and porcine-derived implants. A recent extensive literature review failed to find a benefit to any particular implant in the repair of lower lid retraction,22 suggesting that any of the above implants can be used at the surgeon’s discretion.

Bridging the Options

The management of NK has long been a challenge for ophthalmologists. New therapeutic options, such as self-retained amniotic membranes and drops that deliver human NGF, have provided hope in facilitating the healing of neurotrophic corneal defects. The oculoplastic techniques outlined above can be considered a bridge to these options, a means of minimizing exposure or optimizing the health of the ocular surface in the case of lid malposition. CP

References

- Versura P, Giannaccare G, Pellegrini M, Sebastiani S, Campos EC. Neurotrophic keratitis: current challenges and future prospects. Eye Brain. 2018;10:37-45.

- Sacchetti M, Lambiase A. Diagnosis and management of neurotrophic keratitis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:571-579.

- Ohba E, Dogru M, Hosaka E, et al. Surgical punctal occlusion with a high heat-energy releasing cautery device for severe dry eye with recurrent punctal plug extrusion. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;151(3):483-487.

- Lee SH, Tseng SC. Amniotic membrane transplantation for persistent epithelial defects with ulceration. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;123(3):303-312.

- Brocks D, Mead OG, Tighe S, Tseng SCG. Self-retained cryopreserved amniotic membrane for the management of corneal ulcers. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020;14:1437-1443.

- Alino AM, Perry HD, Kanellopoulos AJ, Donnenfeld ED, Rahn EK. Conjunctival flaps. Ophthalmology. 1998;105(6):1120-1123.

- Dryden RM, Adams JL. Temporary nonincisional tarsorrhaphy. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;1(2):119-120.

- McInnes AW. Temporary suture tarsorrhaphy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142(2):344-346

- Kirkness CM, Adams GG, Dilly PN, Lee JP. Botulinum toxin A-induced protective ptosis in corneal disease. Ophthalmology. 1988;95(4):473-480.

- Ellis MF, Daniell M. An evaluation of the safety and efficacy of botulinum toxin type A (BOTOX) when use to produce a protective ptosis. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2001;29(6):394-399.

- Cosar CB, Cohen EJ, Rapuano CJ, et al. Tarsorrhaphy: clinical experience from a cornea practice. Cornea. 2001;20(8):787-791.

- Stamler JF, Tse DT. A simple and reliable technique for permanent lateral tarsorrhaphy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108(1):125-127.

- Smellie GD. Restoration of the blinking reflex in facial palsy by a simple lid-load operation. Br J Plast Surg. 1966;19(3):279-283.

- Seiff SR, Sullivan JH, Freeman LN, Ahn J. Pretarsal fixation of gold weights in facial nerve palsy. Ophthalmol Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;5(2):104-109.

- Hontanilla B. Weight measurement of upper eyelid gold implants for lagophthalmos in facial paralysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108(6):1539-1543.

- Carruthers JD. Ophthalmologic use of botulinum A exotoxin. Can J Ophthalmol. 1985;20(4):135-141.

- Quickert MH, Rathbun E. Suture repair of entropion. Arch Ophthalmol. 1971;85(3):304-305.

- Marcet MM, Phelps PO, Lai JS. Involutional entropion: risk factors and surgical remedies. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2015;26(5):416-421.

- Anderson RL, Gordy DD. The tarsal strip procedure. Arch Ophthalmol. 1979;97(11):2192-2196.

- Choi CJ, Bauza A, Yoon MK, Sobel RK, Freitag SK. Full-thickness skin graft as an independent or adjunctive technique for repair of cicatricial lower eyelid ectropion secondary to actinic skin changes. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;31(6):474-477.

- Mauriello JA Jr, Mostafavi R. Medial canthoplasty for optimum support of the lower eyelid in 14 patients. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 1996;27(10):869-875.

- Park E, Lewis K, Alghoul MS. Comparison of efficacy and complications among various spacer grafts in the treatment of lower eyelid retraction: a systemic review. Aesthet Surg J. 2017;37(7):743-754.