Championing the Yamane technique

By Naveen K. Rao, MD

We have no consensus on the optimal IOL implantation technique in the absence of capsular support, when an IOL cannot be safely placed in the capsular bag. Options include anterior chamber (ACIOL) placement, iris fixation and scleral fixation. Each of these methods has distinct advantages and challenges.

THE OPTIONS

In the absence of capsular support, here are our options:

- ACIOL. While ACIOL placement has traditionally been the strategy employed by many surgeons, significant concerns are associated with this approach, even with modern open-loop ACIOLs. These require a large (6-mm) corneal or scleral incision, which can induce irregular astigmatism. ACIOL malposition can occur due to lenses that are too large, too small, tilted or placed in eyes with shallow anterior chambers. This can lead to corneal endothelial decompensation and pseudophakic bullous keratopathy, which not infrequently requires explantation of the ACIOL and endothelial keratoplasty.

- Iris fixation of IOLs. This can be a safe and effective alternative. Outside the United States, retropupillary iris claw lenses are available in dioptric power ranges needed for treatment of aphakia. Within the United States, anterior iris claw lenses are available for use as phakic IOLs but are currently not approved or available for treatment of aphakia. Therefore, in the United States, iris-fixation is accomplished by suturing a three-piece IOL to the iris with polypropylene sutures.1 Although this technique can be stable and safe, potential complications include iris chafing, elevated IOP due to pigment dispersion, pupil distortion and bleeding.

SCLERAL FIXATION: THE LEARNING CURVE — IS WORTH IT?

- Transscleral suture fixation. This approach has undergone numerous modifications over the years. Traditionally, 10-0 polypropylene suture was threaded through or around the eyelets of a polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) IOL.2 Due to the risk of suture breakage over time, 9-0 polypropylene became a more popular alternative. Transscleral suture fixation of a PMMA lens can achieve excellent centration of the IOL, with less concern about iris chafing and pigment dispersion; however, it is more time-consuming and requires conjunctival dissection, which can be more difficult in eyes with scarred conjunctiva from prior surgery. A larger (6-mm) scleral tunnel incision is also required due to the non-foldable PMMA material.

- Polytetrafluoroethylene suture. In recent years, the off-label use of polytetrafluoroethylene (Gore-Tex) suture has become popular due to its higher tensile strength and durability.3 But suture erosion through the conjunctiva has been reported, which could lead to late complications, including the need for patch grafts to cover the exposed suture. Also, in recent years, a foldable hydrophilic single-piece acrylic IOL with four eyelets (Akreos AO60, Bausch + Lomb) has been used off-label instead of a PMMA lens. This IOL can be placed through a smaller corneal/limbal incision, but there is still a need to perform a conjunctival peritomy because the sutures are passed through four sclerotomies and the knot is then tied and rotated down. Additionally, there is potential for the hydrophilic acrylic material to opacify during subsequent intraocular surgeries requiring air or gas (vitreoretinal procedures and endothelial keratoplasty).

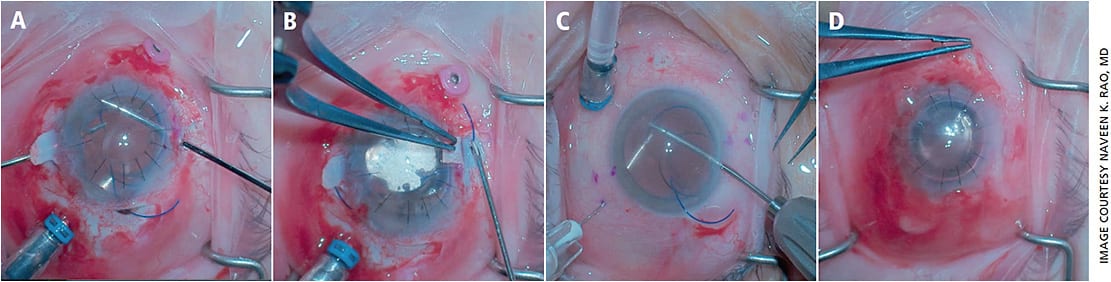

- Sutureless scleral fixation of IOLs. Also known as intrascleral haptic fixation (ISHF), this approach relies on the off-label use of three-piece IOLs. In the glued IOL technique (Figure 1) developed by Amar Agarwal, MBBS, the ends of the IOL haptics are grasped with micrograsping forceps and externalized through two sclerotomies made under scleral flaps.4,5 Then, the haptics are buried into the sclera in intrascleral tunnels, and the scleral flaps and conjunctiva are closed with fibrin glue. Although this technique has many advantages, such as the ability to perform sutureless scleral fixation when visualization through the cornea is suboptimal, disadvantages include the need for significant conjunctival and scleral dissection.

THE YAMANE TECHNIQUE

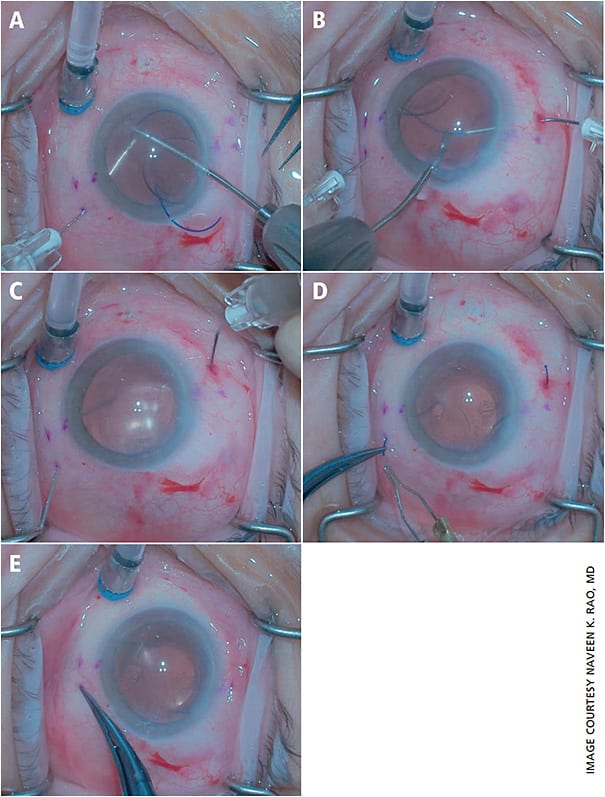

My preferred method of ISHF is double-needle flanged haptic fixation (Figure 2), now popularly known as the Yamane technique. Developed by Shin Yamane, MD, PhD, no conjunctival peritomy is needed in this technique.6 The haptics of a three-piece IOL are docked in the lumen of two needles passed through the sclera. The haptics are externalized by withdrawing the needles, and the ends of the haptics are melted with a low-temperature battery-operated handheld cautery unit. The flanged haptics are then nudged back into the intrascleral needle tracks to seal the sclerotomies and to hold the IOL securely.

The Yamane technique is faster than the other techniques and does not require conjunctival or scleral dissection. This is particularly advantageous in eyes with scarring from prior conjunctival surgery (glaucoma, pterygium, vitreoretinal procedures, ruptured globe repair). This technique also eliminates the need for sutures or glue-assisted closure.

PEARLS AND A FEW PERILS

The benefits of the Yamane technique can be offset somewhat by a few disadvantages. There is a steep learning curve associated with a surgeon’s initial 10 to 20 cases. The process of docking the IOL haptics into needles is technically more difficult than externalizing the haptics with micrograsping forceps, as done in the glued IOL technique. With the Yamane technique, precise symmetry of the length and trajectory of each needle’s tunnel through the sclera is needed to achieve good IOL centration.

Fortunately, surgeons have many pearls at their disposal to get started with the Yamane technique. First, use a lens with haptics made of polyvinylidene fluoride — these haptics are much more resilient and less likely to bend and break compared with haptics made of PMMA or Prolene. My preferred IOL for ISHF is the Zeiss CT Lucia 602 lens. This lens has a hydrophobic acrylic optic.

Second, thin-walled 30g needles are recommended for docking. The lumen of a regular 30g needle is not large enough to accommodate the haptic of most three-piece IOLs. Though some surgeons have used the more widely available 27g needles, the resulting sclerotomies are larger. Also, there is a higher chance of the haptic flanges either sliding out of the scleral tracks and chafing the conjunctiva or slipping into the vitreous cavity, causing the IOL to dislocate.7-9

Third, it’s ideal to practice ISHF in a wet lab setting prior to performing your first case. At the AAO annual meeting, Ashvin Agarwal, MD, and I direct an ISHF skills transfer session, now in its fourth year. Similar labs are available at other ophthalmology meetings around the world. For more surgical tips, including pearls for how to get out of trouble in your first Yamane cases, visit my YouTube channel (bit.ly/2xlencL ). OM

REFERENCES

- Chang DF. Siepser slipknot for McCannel iris-suture fixation of subluxated intraocular lenses. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2004;30:1170-1176.

- Vote BJ, Tranos P, Bunce C, Charteris DG, Da Cruz L. Long-term outcome of combined pars plana vitrectomy and scleral fixated sutured posterior chamber intraocular lens implantation. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141(2):308-312.

- Khan MA, Gupta OP, Smith RG, Ayres BD, Raber IM, Bailey RS, Hsu J, Spirn MJ. Scleral fixation of intraocular lenses using Gore-Tex suture: clinical outcomes and safety profile. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016;100(5):638-43.

- Gabor SG, Pavlidis MM. Sutureless intrascleral posterior chamber intraocular lens fixation. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007;33(11):1851-4.

- Agarwal A, Kumar DA, Jacob S, Baid C, Agarwal A, Srinivasan S. Fibrin glue-assisted sutureless posterior chamber intraocular lens implantation in eyes with deficient posterior capsules. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2008;34(9):1433-8.

- Yamane S, Sato S, Maruyama-Inoue M, Kadonosono K. Flanged Intrascleral Intraocular Lens Fixation with Double-Needle Technique. Ophthalmology. 2017;124:1136-1142.

- Yamane S, Inoue M, Arakawa A, Kadonosono K. Sutureless 27-gauge needle-guided intrascleral intraocular lens implantation with lamellar scleral dissection. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(1):61-6.

- Ganne P, Baskaran P, Krishnappa NC. Re: Yamane et al.: Flanged intrascleral intraocular lens fixation with double-needle technique (Ophthalmology. 2017;124:1136-1142). Ophthalmology. 2017;124(12):e90-e91.

- Yamane S, Sato S, Maruyama-Inoue M, Kadonosono K. Reply. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(12):e91.

About the Author

Suture iris fixation of three-piece IOL

By Daniel Anderson, MD

Despite the simplicity of ACIOLs and the excitement of scleral fixation, iris fixation still holds a special place in the right patient. It is my preferred technique for certain patients with compromised capsular support that is inadequate for posterior optic capture of a sulcus IOL. I’ll explain why.

A REVIEW

The procedure was first described by McCannel in 1976 and, with many studies highlighting pitfalls to avoid, has re-emerged as a viable and safe IOL fixation technique.1 Early concerns of iris chafing leading to pigmentary dispersion glaucoma and cystoid macular edema (CME) have become far less common with the use of a three-piece IOL with a rounded anterior optic edge.2-4 Several studies reported no new cases of CME and found no difference in corneal decompensation when compared to scleral fixation.1-3

Thanks to initiatives by the ASCRS Cataract Clinical Committee, we should all be well aware of the high risk of uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema (UGH) and other complications associated with placing a single-piece acrylic IOL in the sulcus.5 Even with suture fixation, the use of rigid haptics, single-piece IOLs or polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) IOLs have a higher incidence of increased IOP and inflammation.6

Although suture iris fixation has been successful in cases with no capsular support, any remaining structure provides increased stability as well as decreases the risk of a dropped IOL intraoperatively.3,4,7 Large iris defects, extensive iris atrophy or mydriasis also preclude the use of iris fixation. In these cases, I would advocate for a transscleral-flanged or scleral-fixated technique.

Significant advantages for iris fixation include IOL centration with minimal risk of induced IOL tilt.3-6 Also, the risk of intraoperative hemorrhage is significantly less, as are operative difficulty and surgical time.2-4,7 All fixated IOLs carry a risk of re-subluxation. The rates may be higher for iris fixation in children, particularly with history of Marfans; however, most would argue that refixation of an iris-fixated IOL is more successful and less challenging than a transscleral- or scleral-fixated IOL.8 Lastly, the possibility of suture erosion is avoided.

MY TECHNIQUE

My technique is similar to that described by Stutzman.9 After thorough anterior vitrectomy (if required), viscoelastic is used to expand the sulcus space and maintain anterior chamber stability. The three-piece IOL is inserted and positioned in the sulcus space. After instilling a miotic agent, the optic is then anteriorized to achieve optic capture. If there is significant risk of a subluxed IOL, the IOL can be inserted in the anterior chamber with manual positioning of the haptics posterior to the iris.

Some advocate positioning the haptics at 3 and 9 o’clock; however, it may be more advantageous to orient the haptics to allow for the easiest suture pass. Two paracenteses are created directly anterior to the haptics. Viscoelastic can be instilled to better define the haptics. In conjunction with positioning the optic anteriorly with a Sinskey or cyclodialysis spatula, the surgeon can easily visualize the intended suture pass. A 9-0 or 10-0 Prolene suture on a CTC-6 needle is then passed through cornea proximal to the haptic, passed through midperipheral iris incorporating the haptic and then passed distal to the haptic through iris and cornea.

Care should be taken not to make the bite too large or overtighten the suture, as this causes bunching of the iris or peaking of the iris.1,3

The needle is cut off, and the suture ends are retrieved and externalized through the paracentesis with a Sinskey or J-hook. The suture is secured using a modified McCannel technique or Siepser sliding knot and trimmed. The same is then performed for the other haptic. Any adjustment should be made for centration prior to repositioning the optic behind the iris. Using a Sinskey forceps or microforcep, the iris should be manipulated to minimize or eliminate any pupil distortion and a final check for vitreous performed.

THE LITERATURE SUPPORTS IT TOO

Many studies have compared iris fixation to scleral fixation and have report lower complication rates.2-4,7 This is likely due to minimal tissue disruption and lower operative time. The comparative ease of suture iris fixation has been undervalued. In addition, the procedure is repeatable in the event of re-subluxation, as is more common in Marfans.8

Surgeons should strongly consider iris fixation before opting for more technically demanding and invasive procedures, especially when the increased risk of complications could be avoided altogether. OM

REFERENCES

- Por YM, Lavin MJ. Techniques of intraocular lens suspension in the absence of capsular/zonular support. Surv Ophthalmol 2005;509:429-462.

- Soiberman U, Pan Q, Daoud Y, et al. Iris suture fixation of subluxated intraocular lenses. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;159:353-359.

- Condon GP, Masket S, Kranemann C, et al. Small-incision iris fixation of foldable intraocular lenses in the absence of capsule support. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1311-1318.

- Zhang H, Zhao J, Zhang LJ, et al. Comparison of iris-fixated foldable lens and scleral-fixated foldable lens implantation in eyes with insufficient capsular support. Int J Ophthalmol 2016;9:1608-1613.

- Chang DF, Masket S, Miller KM, et al. Complications of sulcus placement of single-piece acrylic intraocular lenses: recommendations for backup IOL implantation following posterior capsule rupture. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2009;35:1445-1458.

- Kim KH, Kim WS. Comparison of clinical outcomes of iris fixation and scleral fixation as treatment for intraocular lens dislocation. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160:463-469.

- Li X, Ni S, Li S, et al. Comparison of three intraocular lens implantation procedures for aphakic eyes with insufficient capsular support: a network meta-analysis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018;192:10-19.

- Yen KG, Reddy AK, Weikert MP, et al. Iris-fixated posterior chamber intraocular lenses in children. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147:121-126.

- Stutzman RD, Stark WJ. Surgical technique for suture fixation of an acrylic intraocular lens in the absence of capsule support. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2003;29:1658-1662.

About the Author

In defense of the anterior chamber IOL

By Michael Patterson, DO

If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

That’s a saying often used in the South, because it is so often apt. While the invention of new surgical techniques such as glued IOLs, scleral-fixated IOLs, iris-fixated IOLs and the like have been greeted with almost universal approval, a seemingly major new “danger” of anterior chamber IOLs (ACIOLs) has arisen. To hear some anterior segment surgeons talk, you would think ACIOLs are beyond reprehensible. Or that everyone has begun to think the Yamane technique (the flanged intrascleral IOL fixation using the double-needle technique first described by Dr. Shin Yamane) is foolproof and poses no danger to the patient.

But the truth is, thousands of patients have had ACIOLs for more than 20 years and are doing just as well today as they were decades prior. Many anterior segment surgeons performing these techniques haven’t scleral depressed in 10 years and therefore have no idea if they are creating retinal holes or tears while operating posterior to the ciliary sulcus. And if you are performing a technique that you do every 2 to 3 months, is it really in the patient’s best interest for you to try a newer, more complex technique that neither you nor your staff are competent in?

THINK IT THROUGH

As a surgeon who does all of the above techniques, I am here to say that sometimes an anterior chamber lens is a fine option. I am not going to listen to the mantra that it is nearly an injustice to your patients to place ACIOLs in their eyes. Do not succumb to pressure from the newer surgeons who are convinced that only their option works. If you have an 85-year-old who has a broken capsule and normal cornea and you size the ACIOL appropriately, you will undoubtedly have a solid outcome without the hassle of the newer techniques.

Also, consider the cost-benefit ratio of these newer techniques. You don’t get paid to use your vitrector when you break a capsule. You don’t get paid to use TISSEEL glue (Baxter Healthcare) for a case in the ASC. Your special high-temp cautery isn’t billed to the patient either in the ASC; I doubt you typically have a high-temp cautery device on the tray.

Even if you do all of these complex maneuvers, the patient will likely see just as well by sliding in an ACIOL. In 2005, Donaldson et al published data in the Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery that showed that thanks to recent advances in ACIOL design, the outcomes were a safe and effective alternative to sutured IOLs.

The issue is that we are judging ACIOLs on past designs when they have significantly improved. New models offer better anterior chamber vault, less movement of the lens, and better fit and design for patieints. Ironically, the same crowd that slams ACIOLs for fear of severe damage to the eye are completely fine with using implantable contact lenses and corneal inlays — both of which have much more concerning safety profiles.

CONTRAINDICATIONS TO KEEP IN MIND

I am a no-spin guy, so let me share some things I think are not good about ACIOLs. I would avoid them in cases of known endothelial compromise. A patient with 2-3+ guttata likely isn’t a good candidate. A shallow anterior chamber is not a good option for the patient. In patients with known uveitis, I tend to avoid these lenses. Lastly, patients with known synechiae in the angle are probably not good candidates for ACIOLs.

The key, as my momma taught me, is to “use your noggin for something else than a hat rack.” You have to think and decide and be a doctor. If the patient isn’t a good candidate for an ACIOL and you aren’t comfortable with other techniques, close the eye and refer to someone else.

MY TECHNIQUE

Here’s what I do. First, I measure the white to white on the IOLMaster 700 (Zeiss). Then, I add 1 mm to that. You will need two different sizes of ACIOLs in your OR most likely, as everyone’s eye is different.

Make sure to review your ACIOL calculations. I have a surgery coordinator and a computer in my OR that runs the ACIOL for every patient when we need the lens during surgery. This eliminates the hassle of always running the calculations for the lens that is so rarely used.

I like to place Miostat (carbachol intraocular solution, USP, Alcon) in the eye before insertion of the ACIOL because it allows the pupil to be maximally constricted and have a better floor for the lens to sit on. While many surgeons place these lenses superiorly, I tend to just slide them in temporally from my normal operating position. Two to three slip knots with 10-0 nylon and you have your wound closed without tension.

Performing a peripheral iridectomy with the vitrector is simple to do and doesn’t typically cause much intraocular bleeding. Simply slide the vitrector under the IOL and behind the iris. Lift upward on the iris, and use a close cut rate to slowly create your peripheral iridectomy.

My experience with all of these techniques shows that a good ol’ anterior chamber lens is a good option for many patients. OM