As physicians, we know that prevention is the best medicine. This is certainly true when it comes to medical professional liability (MPL). The majority of practicing physicians will face at least one MPL claim during the course of their careers, but you can take steps to minimize your risk of a claim or an indemnity payment. While these steps take time, they are well worth the effort.

According to the 2019 Medscape Malpractice Report, which surveyed 4,300 physicians in 29 specialties, 42% of physicians who were sued for medical malpractice spent more than 40 hours on tasks related to the preparation of their defense.

There is not enough time to address all the potential pitfalls in medical practice, but here I present an overview of the MPL landscape and provide some resources to aid you in preventing a claim.

WHAT THE DATA SHOW

MPL varies by specialty and can be generally categorized into low- and high-risk specialties. According to a 2011 article published in The New England Journal of Medicine by Jena AB et al, ophthalmology ranked 19 out of 26 specialties to incur MPL. During this study period, which ranged from 1991 to 2005, 7.4% of physicians across all specialties experienced a new malpractice claim. Only 1.6% of physicians had an indemnity payment, defined as a closed claim in which a payment is made to the plaintiff (Tables 1 and 2). The mean payment varied by specialty, but across specialties it was $274,887. The median payment across specialties was $111,749. The authors of this article projected that, by the age of 45 years, 36% and 88% percent of physicians in low- and high-risk specialties, respectively, were projected to face their first claim. Lastly, this article estimated that by age 65, 99% of physicians in high-risk specialties and 75% of physicians in low-risk specialties will have faced at least one malpractice claim over the course of their careers.

| Physicians facing any claim | Physicians facing an indemnity claim | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specialty | By age 45 | By age 65 | By age 45 | By age 65 |

| Internal medicine and its subspecialties | 54.9% | 88.5% | 12.1% | 34.4% |

| General surgery and surgical specialties | 79.9% | 98.4% | 26.3% | 63.3% |

| Obstetrics and gynecology | 74.1% | 97.2% | 30% | 71.2% |

| Anesthesiology | 56.7% | 90.3% | 16.6% | 53.2% |

| Family medicine | 42.3% | 76.7% | 10.8% | 31.2% |

| Pathology | 37.5% | 80.8% | 5.6% | 28.7% |

| The probabilities of facing a malpractice claim, based on practitioner age and specialty; data from “Malpractice risk according to physician specialty,” Jena AB et al, NEJM, 2011 Aug. 18. | ||||

|

|

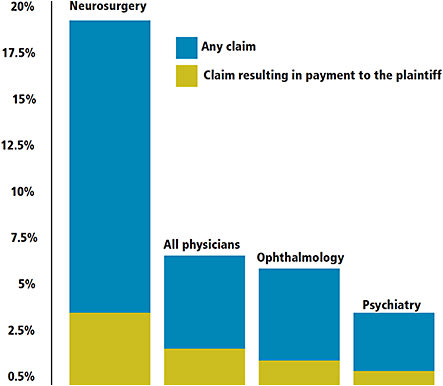

| The approximate chances of a malpractice claim against a practitioner resulting in a payment to a plaintiff. Ophthalmology is compared to neurosurgery (the highest number of malpractice claims), psychiatry (the lowest number of claims) and all physicians; data from “Malpractice risk according to physician specialty,” Jena AB et al, NEJM, 2011 Aug. 18. |

A more recent study by Thompson AC, et al, published in Ophthalmology in 2018 looked specifically at ophthalmology-related professional liability claims between 2006 and 2015. This article analyzed data from the Physician Insurers Association of America (PIAA) and found that, over the study period, 2.2% of all MPL claims were against ophthalmologists. In addition, of all closed claims against ophthalmologists, only 24% resulted in indemnity payments. Compared to 29 other specialties, ophthalmology ranked 12th in the number of claims closed over the study period, but the total indemnity paid placed ophthalmology 17th out of the 30 included specialties.

The average indemnity payment for ophthalmology was $280,227, but this varied widely based on the presenting medical condition. For instance, from 2011 to 2015, the highest average indemnity paid among medical conditions was $567,500, for “corneal opacities and other corneal disorders”; the lowest average indemnity was $213,906, for cataracts.

Also of note, two thirds of all MPL claims against ophthalmologists were dropped, withdrawn or dismissed, and 90% of all verdicts in ophthalmology-related MPL claims were in favor of the ophthalmologist.

In addition, malpractice suits vary by gender, according to both the 2019 Medscape Survey and the article by Thompson et al. Of the Medscape Survey respondents who experienced a malpractice claim, 68% were men and 32% were women, while Thompson et al found that 83.1% of ophthalmology claims were against men and only 11.4% were against women.

Lawsuits are time consuming and they can last years. According to the 2019 Medscape survey, 40% of lawsuits last 1 to 2 years and 11% last longer than 5 years. These data include lawsuits that were dismissed or dropped, so bear in mind that any lawsuit, even those that do not result from medical error, can have a long-lasting impact on your time and quality of life.

MINIMIZE RISK

You can take steps to decrease your risk of a claim. These take time to set up and implement, and there is a cost associated with creating an environment that minimizes risk. But, once you have these best practices in place, you are likely to see the benefit in your work environment. Spending the time to organize your practice and approach toward patient engagement could save you time in the long run, both in prevention and defense.

COMMUNICATION

The 2019 Medscape survey showed that 48% of physicians who faced an MPL claim felt that improved communication would have prevented their suit. As a profession, our success is largely assessed and judged by our ability to communicate. For most, effective communication is a learned skill, and the more time you put into learning, practicing and perfecting it, the better you will be at it.

A study from the Penn State University College of Medicine showed that patients forget up to 86% of what doctors tell them, while they recall up to 85% of spoken information when supplemented with pictographs.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), which is a division of the Department of Health and Human Services, reports that patients forget between 40-80% of what they are told. In addition, approximately half of retained information is actually recalled incorrectly.

Done, et al showed that patients who are educated with video are two to 16 times more likely to recall information accurately. Finding ways to improve patient engagement, understanding and retention can be challenging but critically important.

The AHRQ recommends using the “teach-back method” (described here: https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/literacy-toolkit/healthlittoolkit2-tool5.html ). Among other tools, the Ophthalmic Mutual Insurance Company (OMIC), the largest insurer of ophthalmologists in the United States, endorses the “teach-back method” for its members.

It is important to note that if you experience an MPL claim, every piece of communication from your practice can be used for or against you. This includes:

- Face-to-face discussion (physician and staff)

- Written materials (paperwork, patient education materials, consent forms and marketing materials/advertisements)

- Audiovisual aids (video/animation content utilized in your practice or distributed through your patient portal)

- Web-based materials

- Marketing materials

So, it is important that these are all consistent and follow health literacy standards.

If a patient is not fluent in English, your communication also needs to be in the patient’s native language. To further meet the needs of non-English speaking patients, I recommend the use of a video translator. My department recently added video translation services provided by Pacific Interpreter, and it has been enormously helpful. I always document in my note that I used a native language video interpreter and keep the service online until the patient has completed check-out.

INFORMED CONSENT & PATIENT EDUCATION

I include informed consent and patient education in one section because they are inextricably linked. A strong informed consent cannot occur without excellent patient education.

The strongest informed consent is multimodal and includes a verbal discussion, written patient education materials, videos and web-based content for patients who desire additional information.

From a legal standpoint, your informed consent includes every conversation and piece of educational material your patient receives from your practice, including verbal descriptions, instructions, handouts, videos, web-based material and, yes, marketing materials.

OMIC recommends plain language consent forms tailored for specific procedures, and it also recommends you provide your patients with a copy of their consent form. OMIC’s website is largely open to the public and offers a plethora of information and resources, including downloadable informed consent templates in English and Spanish (https://tinyurl.com/upxjsxg and https://tinyurl.com/v5z3r8q respectively). Give patients enough time to ask questions, and always give them another opportunity to ask questions after reviewing the material you provide.

You should provide patient education materials that meet health literacy standards. Health literacy is defined by the Department of Health and Human Services as, “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.”

In my practice, I use the trifold printed brochures and the electronic patient handouts provided by the AAO. These are peer-reviewed annually for accuracy and currency, and are updated annually. They meet health literacy guidelines to improve understanding and are available in English and Spanish.

Multiple studies have shown that video education enhances understanding and recall. A 2005 study by Pager CK published in The British Journal of Ophthalmology found that video education prior to cataract surgery:

- Showed patients what to expect from surgery

- Lead to a significant increase in patient understanding of surgery

- Decreased anxiety associated with surgery

- Yielded higher satisfaction rates with surgery

Some providers of ophthalmology-specific patient education videos include the AAO, Patient Education Concepts and Rendia.

Lastly, you should provide up-to-date web-based information. If you don’t provide it, patients may look for it elsewhere. Make sure your web content also meets health literacy standards. An easy way to accomplish this is to link directly to the AAO’s patient education website, Eyesmart (www.aao.org/eye-health ). Another option is to license content to include on your practice website. If you do this, make sure it is maintained appropriately for currency, accuracy and health literacy standards.

DOCUMENTATION

There is no substitute for good documentation — it is worth the extra time. Most malpractice lawsuits are not filed immediately. The medical record is how you will recreate and show what occurred. If data are missing, this will be hard to do.

Keeping a detailed and comprehensive account of your thought process and communications is important. If you can show in the record that your approach was methodical, comprehensive and included good communication, this may protect you.

Document all your conversations and materials utilized for education, and include written documentation about risks, benefits, alternatives and expectations. Managing expectations can be a time-consuming task, but, if you and your patient have the same expectation, there are no surprises.

In the event an outcome is less than desired, you will not have to back track to explain what happened to them. All your efforts to communicate, educate, inform and prepare may not help you if your documentation is poor.

CONCLUSION

Complications, adverse events and patient grievances happen. This does not mean medical error or deviation from the standard of care has occurred, but it can lead to a claim.

It is almost impossible to practice medicine for a lifetime and avoid a lawsuit. But, if you develop a systematic and consistent approach to patient engagement, communication, education and record keeping, you will go a long way to preventing or successfully defending an MPL claim. OM