After being deprived for months of doing what we love due to a global pandemic, surgeons are starting to get back to the OR, applying the amazing technology that transformed cataract surgery over the last decade. As the lights turn back on, surgical centers are eagerly firing up their femtosecond lasers, turning on 3-D microscopes, waking up smart phacoemulsification machines designed for small incisions and placing advanced IOLs in patients. It is amazing what we have accomplished in the last 15 to 20 years as we strive to learn and deliver the best possible care for each patient.

However, a piece of the past still lingers for many patients: postoperative drops. Here, I will highlight the postoperative drop burden and some strategies for overcoming it.

OUR PARADOX

The requirement of drops brings to light a significant paradox in cataract surgery.

Most doctors’ medical decisions, adoption of technology and advancement of care is focused on further applying this knowledge in surgery, all with the common goal to have improved outcomes and high patient satisfaction. At the same time, our staff’s happiness and wellbeing are a priority, as any successful practice is built on their shoulders. These elements are challenged when staff and patients carry the burden of drops for cataract surgery.

The typical patient is asked to buy three different medications with out-of-pocket expenses up to hundreds of dollars and rising. Based on CMS data and our survey of physicians, within Medicare, the cost of the drug combination used for drop therapy ranges from a low of $175 to a high of $431 per eye, with a weighted average of $323.1

Once these medications are obtained, the next instructions include use of about 114 drops after each surgery for a month or so. That is, if patients remember each dose and are able to get the drop on the eye instead of the cheek or forehead. We advocate for our patients but encumber them with medication cost, compliance and side effects. How often do patients with amazing results instead digress and share concerns about these darn drops? We often agree, nod and move on.

You also do not need to dig deep to expose the burden on staff. They are the ones taking the calls, explaining the regimen, talking to the pharmacy and stuck seeing nicely designed self-made charts patients can’t help but share. How many times has your staff triaged a call with a patient’s worry about putting in extra drop by accident or been asked, again, how long a wait between drops? Somehow this is just accepted and part of the status quo, shifting responsibility and costs to patients. Yet this disconnect from cataract advances in many other aspects is inconsistent with a surgeon’s goal to lessen patient’s burden with surgery.

REVIEWING THE LITERATURE

A driving force disrupting medications for cataract surgery began overseas. In Europe and Japan, studies emerged showing up to a five-fold decrease in endophthalmitis with use of intracameral antibiotics (ICABs).2,3 Follow-up studies for safety in the eye demonstrate that even full-strength intracameral moxifloxacin (ICM) is not damaging to the corneal endothelium.4 Another study in Sweden showed there is no additional benefit of topical antibiotics when ICABs are used perioperatively.5 In fact, both the 2011 AAO Cataract Preferred Practice Pattern Guidelines and a 2011 ASCRS Cataract Clinical Committee review of endophthalmitis prevention noted stronger evidence supporting direct intracameral injection than for any other method of antibiotic prophylaxis,6,7 and surveys show that ICAB use is increasing. ASCRS surveys reveal that surgeon’s injection of ICAB was 14% in 2007 and rose to 36% in 2014.8 Of interest, this same 2014 survey showed that 67% of surgeons believe ICAB prophylaxis is very important, a significant increase from 2017 (54%).

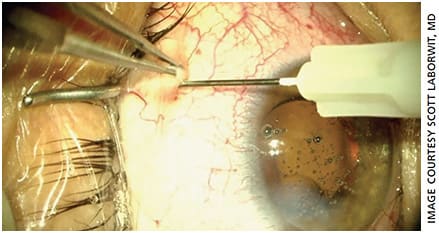

Since topical antibiotics are not FDA approved for routine cataract surgery, the off-label delivery into the anterior chamber to eliminate the use of topical antibiotics is a parallel consideration. Of note, antibiotic drops are still used the day of surgery in the surgical center during dilation, and povidone 5% is applied during the scrub. One example of use is drawing generic moxifloxacin ophthalmic solution 5% out of a medication bottle (Apotex Corp.) and diluting it with balanced salt solution (BSS) in a 1 ml drug to 4 ml BSS ratio (Figure 1). Once the corneal wounds are water seal tight, 0.3 cc of this dilution is placed into the anterior chamber. Alternatively, a compounding pharmacy could provide the medication. Furthermore, as cited earlier, studies confirm there is not an additional benefit with topical antibiotics when placing ICAB.5 This initial incremental change lessens your patient’s medication burden by one. It’s the start of your evolution in balancing all considerations in caring for your cataract patients.

INTRAOPERATIVE STEROIDS

The next step in our quest toward reducing the postoperative drop burden is intraoperative steroid placement. This suspension is milky, cloudy in nature and impacts a surgical choice of location and formulation. Our uveitis colleagues paved the way, establishing the safety and efficacy of sub-Tenon’s triamcinolone (STK) placement to manage anterior chamber inflammation in their chronic uveitis patients.

One consideration is the use of STK acetate injectable suspension 40mg/ml (Kenalog-40). Dr. Gills reported the use in cataract surgery of STK placement, 7 mm posterior to the superior nasal limbus.9 Combined with anterior chamber antibiotics, this allowed him to eliminate need for all drops after cataract surgery. Consider adjusting to a lower total volume of STK, given the advances in cataract surgery creating less trauma to the eye. Using a lower dose also may minimize risks of an IOP elevation. One example is using 0.1 cc of Kenalog-40 STK, 7-mm superior nasal (Figure 2).10 Using less volume allows for easier placement and less anterior migration that can be noticed by patients, and it may have a greater impact on IOP elevation. This is a low-cost alternative with reasonable efficacy and safety.

INNOVATION INCREASES OUR OPTIONS

Compounded mixtures of moxifloxacin and steroids (Tri-Moxi, Imprimis) can be placed in the anterior vitreous. Steroid and antibiotic compounded mixtures effectively allow for a surgery without drops, and cost is reasonable.11 However, anterior segment surgeons are often less comfortable with pars plana or transzonular injections, having trained to avoid the vitreous space.

Among the other recently introduced options is a hydrogel insert that taper-releases 0.4 mg of dexamethasone (Dextenza, Ocular Therapeutix) over a 4-week period. Dextenza is a noninvasive, preservative-free, intracanalicular insert that often eliminates the need for steroid drops postoperatively. It can be easily removed in the office if the patient experiences an elevation of IOP.

Another recent innovation is dexamethasone intraocular suspension 9% (Dexycu, EyePoint Pharmaceuticals) placed at the end of surgery. This commercially available product uses 0.005 ml of steroid injected into the posterior chamber inferiorly behind the iris at the end of ocular surgery.12 A patient may notice the opaque, white medication if it migrates from its intended placement to the pupil or anterior chamber, so it is best to explain this to patients before they leave the surgical center to avoid a call later. Having the steroid placed at the time of surgery eliminates the need for anti-inflammatory drops following surgery.

Some surgeons are concerned about stopping the NSAID since the steroid is placed during surgery. However, studies assessing impact of NSAIDs in cataract surgery have mixed results, and several state that NSAIDS after cataract surgery do not significantly protect from CME.13,14 A surgeon should still consider use of these drops in patients with high risk for macular edema. Of interest, STK is often used as a treatment for CME when drops fail.

The fine print

When working toward eliminating drops, consider some potential pitfalls. The use of incremental changes, monitoring protocols and outcomes are critical for success. Here are a few to consider when using perioperative medication:

- Actively alert your team to monitor for rebound iritis. Typically, patients with breakthrough inflammation often complain of mild light sensitivity, slight blur of vision and/or diffuse pink color change of conjunctiva a week or two after surgery. Make certain staff can triage these calls, and the doctor should not hesitate to treat with steroid drops if necessary. It is also critical to train and educate staff to properly distinguish rebound iritis from a potential endophthalmitis.

- Shake well, often and try to avoid partial use from the vial. Triamcinolone acetate is a suspension that settles quickly and requires delicate attention when handling. If it is not shaken well in the original vial before it is drawn into a syringe, a patient may get a very dilute or very concentrated dose. This in turn would impact risk for rebound iritis or elevation of IOP.

- Seal wounds tight first. The corneal incisions need confirmed water seal closure prior to placement of anterior chamber antibiotic to avoid risk of leakage. Once placed further, hydration of the wounds could impact the drug concentration. Testing the wound prior to medication placement assures a proper and consistent delivery of antibiotic concentration.

ONE SIZE DOES NOT FIT ALL

Utilizing a fewer drops approach should not apply to every patient. For example, if a patient is severely allergic to moxifloxacin, use another class of medication in drop form postoperatively. Another example to consider is in those patients with very poor lid hygiene or severe lid laxity. In these patients, use an antibiotic ointment after surgery given a potential source for infection. Additionally, avoid STK placement in patients with a history of glaucoma or herpes simplex keratitis. Instead, a topical steroid is appropriate in these cases to allow for a quick taper if necessary. Alternatively, consider Dextenza placement in these patients; it allows the option to easily remove from the lacrimal system, thus eliminating, if necessary, the steroid side effects. Lastly, consider a 12-week course of a topical NSAID in patients at high risk for macula edema after surgery. Some examples include a patient with macular pucker or retinal hemorrhages near the macula from diabetic retinopathy, or a branch retinal vein occlusion.

When necessary to use drops for cataract surgery, simply educating the patient “why” is appreciated, as they are a partner in wanting the best outcomes. In addition, very few patients may simply elect to use drops instead of perioperative medication. Explain to your patient all options and consider a separate consent form if eliminating drops.

CONCLUSION

The first step toward eliminating drops is to review the current studies and become familiar with safe options and outcomes. Next, adapt a technique consistent with your comfort level in surgery. Incremental changes will allow you to pivot to new dosing, delivery or products if necessary. This change will then shift the burden of medications away from your patients and staff. The efforts will be more in line with other advances in cataract surgical care, while safely allowing a surgeon to advocate for an overall improved patient experience in cataract surgery. OM

One surgeon’s journey

After reviewing the literature in 2015, I found compelling evidence for the use of ICM. The decision was to carefully mimick the dose used in a large study. Therefore I used moxifloxacin 0.05% out of a bottle and diluted with BSS. The ratio was one-part drug to four-part BSS with delivery of 0.3 cc into the anterior chamber of the eye at the end of each cataract surgery. The topical antibiotic was eliminated at this point. After 6 months of monitoring safety and outcomes, we eagerly took the next step to eliminate all drops patients would need to buy for surgery.

Finding addition studies and reports regarding perioperative anti-inflammatory medication was the roadmap for the next step. We decided to place Kenalog-40 into the sub-Tenon’s space, 8 mm from the limbus in the supra-nasal quadrant by having the patient look down at the end of surgery. This extraocular location was desirable compared to using the anterior vitreous space. It was also a familiar technique having used STK in the past for patients with chronic uveitis. Initially, we used 0.3 cc after ICM placement; however, there were some cases of persistent IOP elevation. Three patients required excision of STK, which quickly allowed the IOP to return to baseline without drops.

In 2019, we decided to reflect on these outcomes and adjust the dose of STK since the advances in cataract surgery often allow for significantly lower average ultrasound and trauma in the eye. Thus, we lowered the dose from 0.3 cc to 0.1 cc. This eliminated the concern of persistent IOP elevation with no patients requiring excision of STK. Of note, there was not a significantly noticeable increase in rebound iritis with this adjusted dose. Also, we established a protocol to shake vigorously the suspension of Kenalog, use the entire vial and place in a very large syringe. This allows for more shaking before dosing to the table each case, thus assuring proper drug dosing.

Another consideration was the need for additional staff training to review symptoms of rebound iritis as compared to endophthalmitis. We gave instruction to bring in any patient if there was even a slight concern of infection and increase diligence with follow-up phone calls or in-office examinations. The initial goal to eliminate drops in cataract surgery was to advocate for patients while maintaining best practice outcomes. The true impetus was rising costs of medications and fear of compromising anti-infective coverage with use of generic drops. It was surprising how much patients actually noticed this effort and appreciated not having to buy and use drops routinely. In fact, the practice grew as new patients self-referred wanting the same care as their friend or family. Also, staff felt a relief from the burden of giving drop instructions along with taking many calls of patient complaints and concerns. The time saved was equivalent to gaining a full-time staff person back in the clinic.

Eliminating drops for routine cataract surgery is one of the greatest accomplishments in my 20-year career, in line with my goals of advocating for my patients and staff while advancing technology and techniques in cataract surgery.

REFERENCES

- Andrew Chang & Co., LLC. Analysis of the economic impacts of dropless cataract therapy on Medicare, Medicaid, state governments, and patient costs. October 2015.

- Barry P, Gardner S, Seal D, et al. Clinical observations associated with proven and unproven cases in the ESCRS study of prophylaxis of postoperative endophthalmitis after cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg 2009; 35:1523-1531.

- Matsuura K, Miyoshi T, Suto C, Akura J, Yoshitsugu I. Efficacy and safety of prophylactic intracameral moxifloxacin injection in Japan. J Cataract Refract Surg 2013;39:1702-1706.

- Chang DF, Prajna NV, Szczotka-Flynn LB, et al. Comparative corneal endothelial cell toxicity of differing intracameral moxifloxacin doses after phacoemulsification. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2020;46:355-359.

- Friling E, Lundström M, Stenevi U, Montan P. Six-year incidence of endophthalmitis after cataract surgery: Swedish national study. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2013;39:15-21.

- American Academy of Ophthalmology. Cataract in the Adult Eye; Preferred Practice Pattern. San Francisco, CA, American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2011.

- Ku JJ, Wei MC, Amjadi S, Montfort JM, Singh R, Francis IC. Role of adequate wound closure in preventing acute postoperative bacterial endophthalmitis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38:1301-1302.

- Chang DF, Braga-Mele R, Henderson BA, Mamalis N, Vasavada A; ASCRS Cataract Clinical Committee. Antibiotic prophylaxis of postoperative endophthalmitis after cataract surgery: Results of the 2014 ASCRS member survey. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2015;41:1300-1305.

- Gills JP. Reducing the need for postoperative eye drops. Ophthalmology Times. October 1, 2013. https://www.ophthalmologytimes.com/view/reducing-need-postoperative-eye-drops . Accessed July 1, 2020.

- LaBorwit SL, Stutman R. Intra-operative medications used during cataract surgery to safely substitute the need for a patient having cataract to purchase medication. ASCRS paper presentation, May 2020.

- Fisher BL, Potvin R. Transzonular vitreous injection vs a single drop compounded topical pharmaceutical regimen after cataract surgery. Clin Ophthalmol. 2016;10:1297-1303. Published 2016 Jul 18.

- Donnenfeld E, Holland E. Dexamethasone intracameral drug-delivery suspension for inflammation associated with cataract surgery: a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III trial. Ophthalmology. 2018;125:799-806.

- Ndegwa S, Cimon K, Severn M. Intracameral antibiotics for the prevention of endophthalmitis post-cataract surgery: review of clinical and cost-effectiveness and guideline [Internet]. Ottawa: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2010 (Rapid Response Report: Peer-Reviewed Summary with Critical Appraisal). [cited 2010-10-07]. Available from: http://www.cadth.ca/index.php/en/hta/reports-publications/search/publication/2683 . Accessed July 1, 2020.

- Kim SJ, Schoenberger SD, Thorne JE, Ehlers JP, Yeh S, Bakri SJ. Topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cataract surgery: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:2159-2168.