A 23-year-old female patient presented after experiencing redness, bilateral blurred vision and burning in both eyes for two days. She reported normally seeing well without glasses and had no significant ocular history. On initial exam, her exam findings were as follows:

| OD | OS | |

|---|---|---|

| Visual Acuity (sc) | 20/400 PH 20/150 | CF 5 ft, PH 20/100 |

| Intraocular pressure (mmHg) | 26 | 24 |

| Pupils | No rAPD | No rAPD |

| Refraction (SE) | -9.25 BCVA 20/40 |

-7.75 BCVA 20/30 |

Slit lamp exam showed: conjunctiva: injected OU; cornea: clear OU; anterior chamber: shallow peripherally, deep centrally, quiet OU.

Gonioscopy revealed appositional closure 360 OU, dilated fundus exam showed an sharp and pink optic nerve, no disc edema, trace macular striae, shallow peripheral choroidal effusions OU.

THE PLOT THICKENS

On further questioning, the patient reported a history of epilepsy and had started taking topiramate (Topamax, Janssen) 12 days prior to presentation. She took 50 mg for one week and increased the dose to 100 mg three days prior to presentation. Her symptoms began within hours of taking the medication on the third day.

While primary acute angle-closure glaucoma was on the differential diagnosis, this typically presents unilaterally and is more common in patients with a history of hyperopia or anatomic narrow angles. Thus, secondary angle-closure glaucoma was higher on the differential diagnosis. Several mechanisms cause secondary angle-closure, either through pushing the iris forward from behind or pulling the iris forward into contact with the trabecular meshwork.

The bilateral condition made a medication-induced angle closure most likely. Many medications cause secondary angle closure, including tricyclic antidepressants, MAO-inhibitors, antihistamines and sulfa-based drugs like topiramate.1 Given the timing of our patient’s symptoms, occurring within two weeks of starting topiramate, and the presentation — bilateral, myopic shift and ciliochoroidal effusions — topiramate-induced angle-closure glaucoma (TiACG) was the most likely diagnosis. Once informed, the patient promptly discontinued topiramate and started topical cyclopentolate and prednisolone drops. Within a week, her vision returned to 20/20 without correction, the angles opened, IOP returned to the teens and choroidal effusions resolved bilaterally.

HOW TO INCREASE AWARENESS?

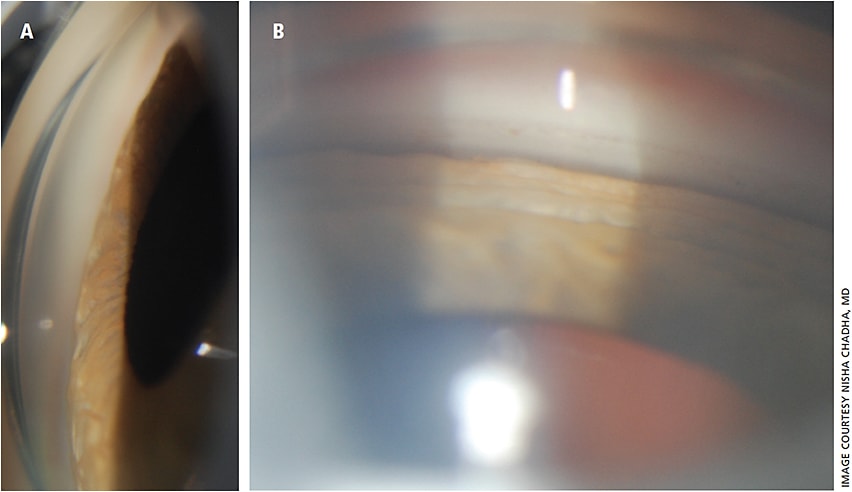

Since TiACG was first reported by Banta et al. in 2001, many other cases have appeared in ophthalmology literature.2-6 TiACG usually presents with sudden, bilateral decrease in vision due to myopic shift from topiramate-induced ciliary body edema. Clinical exam demonstrates shallow anterior chamber from forward rotation of the lens-iris diaphragm, closed angle on gonioscopy and choroidal effusions (Figures 1 and 2).

Because most of these case reports appear in ophthalmology journals and because many of our prescribing colleagues are not ophthalmologists, we were inspired to design an educational intervention with the two-fold goal of both assessing and enhancing their awareness of this entity. We targeted resident physicians training in psychiatry and neurology. Our brief intervention included a pretest and survey, 30-minute lecture describing TiACG and a post-test and survey.

Pretest inquired about presentation of TiACG, its timing and treatment and dosage, while pre-survey assessed prescribing patterns. We inquired about how often and for what purpose they prescribed topiramate and if prescribers were familiar with topiramate’s ocular side effects. We asked if they counseled their patients on the possibility of adverse ocular effects.

Following pretest and presurvey, we presented a case-based presentation on TiACG, describing its typical presentation: sudden, bilateral decrease in vision usually within two weeks of initiating topiramate therapy at doses of 50 mg or more.2-4,6,7 We emphasized that prompt recognition of TiACG is essential for accurate treatment and optimal visual recovery. Unlike pupillary block angle closure, TiACG is not relieved with laser iridotomy — it requires medication discontinuation with supportive therapy for resolution of angle closure along with urgent ophthalmology referral if the patient presented with symptoms.

SURVEY SAYS …

A total of 10 psychiatry and eight neurology residents participated in the study. Among psychiatry residents, nine out of 10 prescribed topiramate at least yearly, most commonly for depression and bipolar disorder. Five out of eight neurology residents prescribed topiramate monthly, mostly for migraine and epilepsy. Pretest evaluation indicated none of the psychiatry residents were familiar with the ocular side effects of topiramate and only three neurology residents were aware of this side effect. On pretest, at least half the residents did not know when TiACG most commonly occurs following initiation of topiramate, or at which dosage TiACG frequently occurs. After the lecture, over 90% of participants responded to these queries correctly.

Postsurvey, all psychiatry and neurology residents indicated they planned to counsel their patients on TiACG.

CONCLUSION

TiACG is a vision-threatening complication that is reversible when managed appropriately. Our study indicated prescribers of topiramate are often unaware of its ocular side effects and thus do not counsel their patients about it. We found that a brief lecture effectively increased prescriber’s understanding of the presentation and management of TiACG. Continued efforts are necessary to educate prescribers, which leads to better patient selection and counseling when prescribing topiramate.

Many systemic medications, such as hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil, Sanofi-Synthelabo), have known ocular side effects8 that patients are often counseled about prior to initiation. Despite the rarity of these side effects, the potential for irreversible damage has made providers, even non-ophthalmologists, aware of the importance of counseling patients prior to initiating these medications. Topiramate, a popular anticonvulsant with off-label use for bipolar disorder and antipsychotic-induced weight gain, similarly can cause a vision-threatening side effect in the form of angle-closure glaucoma; patients should be aware of this side effect. OM

REFERENCES

- Baig N. Drug-induced Glaucoma. The Hong Kong Medical Diary. Available: http://www.fmshk.org/database/articles/03mb6_5.pdf . Accessed June 19 2017.

- Grewal DS, Goldstein DA, Khatana AK, Tanna AP. Bilateral angle closure following use of a weight loss combination agent containing topiramate. J Glaucoma. 2015;24:132-136.

- Banta JT, Hoffman K, Budenz DL, Ceballos E, Greenfield DS. Presumed topiramate-induced bilateral acute angle-closure glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;132:112-114.

- Rapoport Y, Benegas N, Kuchtey RW, Joos KM. Acute myopia and angle closure glaucoma from topiramate in a seven-year-old: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:96.

- Abtahi SH, Abtahi MA, Roomizadeh P, Kasaei Z. Discrimination of topiramate induced angle closure glaucoma from primary angle closure glaucoma: the triple of age, pattern of clinical presentation and drug history. Arch la Soc Esp Oftalmol (English Ed. 2013;88:83-84.

- Fraunfelder FW, Fraunfelder FT, Keates EU. Topiramate-associated acute, bilateral, secondary angle-closure glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:109-111.

- Symes RJ, Etminan M, Mikelberg FS. Risk of angle-closure glaucoma with bupropion and topiramate. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133:1187-1189.

- Mavrikakis I, Sfikakis PP, Mavrikakis E et al. The incidence of irreversible retinal toxicity in patients treated with hydroxychloroquine: a reappraisal. Ophthalmology. 2003; 11:1321-1326.