Glaucoma’s growing prevalence in the US

The reasons: An increasing and aging population and a larger population of minorities.

By Dianna Liu, MD and Angelo P. Tanna, MD

The prevalence of glaucoma in the United States is on the rise. It is important to prepare for the scale of this event as we plan the delivery of ophthalmic care over the next 30 years. This is especially true in light of the growing gap between need and supply of ophthalmologists in the US. The Association of American Medical Colleges projects that by 2020 more than 6,000 additional ophthalmologists will be needed, which is a 28% increase from the year 2000, one of the highest percentages increases needed of all medical specialties.1

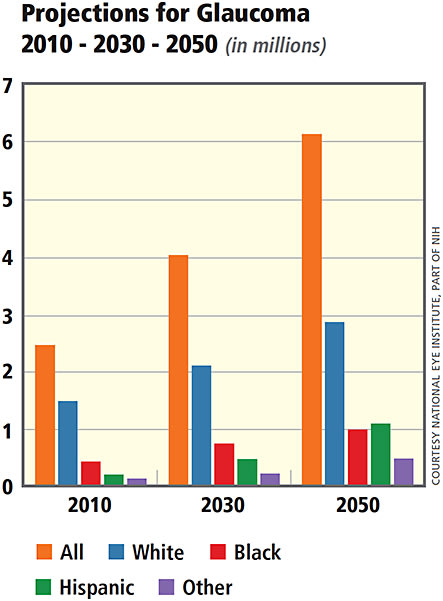

The number of persons in this country with glaucoma is anticipated to increase to 6.3 million by 2050. In 2010, 2.7 million people had glaucoma.

https://nei.nih.gov/eyedata/glaucoma

COURTESY NATIONAL EYE INSTITUTE, PART OF NIH

GLAUCOMA AND AGE

The baby boomers

The demand comes from both a growing and aging population. Age is strongly associated with glaucoma prevalence.

The U.S. Census Bureau predicts this country’s population will grow from 324 million in 2016 to 398 million in 2050.2 The population will be older, with the median age increasing from 37 years in 2012 to 41 years in 2050. Furthermore, 22% of the population in 2050 is projected to be 65 years or older compared to only 15% in 2015. The population of persons 65 years and older is projected to become larger than the population under 18 by 2035.2 This is the result of an aging baby boomer population who will all be 65 or older by 2029.

GLAUCOMA AND RACE

Aging minority populations

In the Baltimore Eye Survey, white subjects 80 years or older had a little over two-fold higher prevalence of glaucoma compared to those ages 40 through 49.3 An even more striking association between older age and glaucoma prevalence is seen in African Americans and Hispanics, with about a nine-fold increased prevalence of glaucoma in their eighth decade of life as compared to those between 40 and 49 years of age.3-8

In 2011, 2.71 million people in the United States had primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG). By 2050, it is estimated that 7.32 million people will have POAG.5 It is not just increasing life spans of Americans, however, that will drive this dramatic increase in POAG prevalence.

Growing populations of minorities

The U.S. Census Bureau projects there will be an increase in the population of black, Asian and most notably Hispanic Americans from 17% in 2012 to 34% by 2050.2 The prevalence of OAG and ocular hypertension is three-fold higher in blacks and Hispanics than in whites, and this will have a dramatic impact on the overall prevalence of glaucoma in the US.3,6,7 Minority populations not only have an increased prevalence of glaucoma, but also tend to have more severe glaucoma at the time of diagnosis and increased risk of blindness.

Population-based prevalence studies have shown that blacks develop glaucoma at a younger age (10 years earlier) and have an increased risk of blindness compared to whites.9 Glaucoma is the most frequent cause of bilateral blindness in Hispanics.4 Earlier detection of the disease and earlier intervention is required to reduce the risk of severe vision loss.

Diabetes

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 29.1 million people or 9.3% of the U.S. population has diabetes.10 Diabetes is a risk factor for development of glaucoma, especially among Hispanics. The Los Angeles Latino Eye Study found that OAG prevalence was 40% higher in participants with type 2 diabetes than those without.11 A meta-analysis of 13 studies has also shown a significant association between diabetes and primary open-angle glaucoma in a variety of populations.12 These findings are also supported by a genetic instrumental variable study.13 As the total diabetes prevalence continues to increase from 14% in 2010 to a projected 21% to 31% in 2050, we can expect this increase to contribute to a higher prevalence of glaucoma.14

Asians and angle closure

While POAG is the most common glaucoma in the United States, angle closure may become increasingly common with the changing demographics of the U.S. population. U.S. Census data do not clearly differentiate among the different Asian populations. However, Asian Americans consist of a diverse group and glaucoma prevalence varies among these Asian populations. For Chinese Americans, the risk of developing primary angle-closure glaucoma is at least equal to that of developing POAG.15,16 But, Vietnamese Americans have a higher prevalence of primary angle closure (26.8%) compared to Caucasians and African Americans,17 with almost half of Vietnamese Americans aged 55 or older having narrow angles.18 In one study, 69% of a Chinese-American population with glaucoma or suspicion of glaucoma had narrow angles.19

Hyperopia

Hyperopia is a major risk factor for angle closure among Asians.20 As the education levels of immigrants and next-generation Asians increases, we anticipate that the prevalence of hyperopia in this population will decrease, as will the prevalence of angle closure. Improved socioeconomic and educational status could favorably impact the risk of the development of angle closure disease in these ethnic groups.

Conclusion

It is clear that glaucoma will continue to evolve with the growing, aging and diversifying population in the United States. It is important for ophthalmologists to anticipate and prepare for the increased disease burden to effectively meet the needs of patients. This will likely necessitate harnessing all available technology to improve the detection of disease and identify and effectively treat those at highest risk of significant vision loss. OM

REFERENCES

1. Physician Supply and Demand: Projection to 2020. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Progressions, October 2006.

2. 2014 National Population Projections; Summary Tables. Table 1/ Table2/ Table 6/ Table 14. U.S. Census Bureau. Web. 3 Jan. 2016. https://www.census.gov/population/projections/data/national/2014/summarytables.html.

3. Tielsch JM, Sommer A, Katz J, Royall RM et al. Racial variations in the prevalence of primary open-angle glaucoma. The Baltimore Eye Survey. JAMA. 1991; 266: 369-374.

4. Quigley HA, West SK, Rodriguez J, Munoz B, et al. The Prevalence of Glaucoma in a Population-Based Study of Hispanic Subjects, Proyecto VER. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1819-1826.

5. Quigley HA, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:262–267.

6. Varma R, Ying-lai M, Francis BA, et al. “Prevalence of open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension in Latinos: The Los Angeles Latino Eye Study.” Ophthalmology. 2004; 111:1439-1448.

7. Vajaranant TS, Wu S, Torres M, Varma R. The Changing face of primary open angle glaucoma in the United States: Demographic and Geographic Changes from 2011-2050. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012 Aug: 154: 303-314.

8. The Eye Diseases Prevalence Research Group. Prevalence of open-angle glaucoma among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol 2004 Apr; 122: 532-538.

9. Sommer A, Tielsche JM, Katz J, et al. Racial differences in the cause-specific prevalence of blindness in East Baltimore. N Engl J Med 1991, 325: 1412-1417.

10. National Diabetes, Statistic Report, 2014 CDC. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/2014-report-estimates-of-diabetes-and-its-burden-in-the-united-states.pdf

11. Chopra V, Varma R, Francis BA, Wu J, Torres M, Azen SP; Los Angeles Latino Eye Study Group. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and the risk of open-angle glaucoma: The Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2008 Feb;115:227-232.

12. Zhou M, Wang W, Huang W, Zhang X. Diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for open-angle glaucoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014 Aug 19; 9: e102972.

13. Shen L, Walter S, Melles RB, Glymour MM, Jorgenson E. “Diabetes Pathology and Risk of Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma: Evaluating Causal Mechanisms By Using Genetic Information.” Am J Epidemiol. 2015 Nov 25. Epub Ahead of print.

14. Boyle JP, Thompson TJ, Gregg EW, Barker LE, Williamson DF. “Projection of the year 2050 burden of diabetes in the US adult population: dynamic modeling of incidence, mortality and prediabetes prevalence. Popul Health Metr. 2010; 8:29.

15. Zhao J, Sui R, Jia L, Ellwein LB. Prevalence of glaucoma and normal intraocular pressure among adults aged 50 years or above in Shunyi County of Beijing. Chin J Ophthalmol. 2002;38:335–339.

16. Baskaran M, foo RC, Cheng CY, Narayanaswamy AK, Zheng YF, et al. The prevalence and types of glaucoma in the an Urban Chinese Population: the Singapore Chinese Eye study. Jama Ophthalmol 2015 Aug; 133 (8): 874-80.

17. Peng PH, Manivanh R, Nguygen N, Weinreb RN, Lin SC. Glaucoma and clinical characteristics in Vietnamese Americans. Curr Eye Res. 2011 Aug; 36 (8): 733-8.

18. Nguyen N, Mora JS, Gaffney MM, et al. A high prevalence of occludable angles in a Vietnamese population. Ophthalmology. 1996;103:1426–1431.

19. Seider MI, Pekmezci M, Han Y, Sandhu S, Kwok SY, Lee RY, Lin SC. High prevalence of narrow angles among Chinese-American glaucoma and glaucoma suspect patients. J Glaucoma. 2009 Oct-Nov; 18 (8): 578-81.

20. Cho HK, Kee C. Population-based glaucoma prevalence studies in Asians. Surv Ophthalmol 2014 Jul- Aug; 59 (4): 434-447.

About the Authors | |

| Dianna Liu, MD is an ophthalmology resident at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicne, Chicago. |

| Angelo P. Tanna, MD, is associate professor of ophthalmology and director of the Glaucoma Service at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago. E-mail him at atanna@northwestern.edu

|