Postoperative inflammation primer

Cataract surgeons have the tools to prevent post-op inflammation — we just have to remember to use them.

By Gregg J. Berdy, MD

We know it’s going to happen. When we perform cataract surgery, the resultant tissue trauma incites inflammation. While modern phacoemulsification surgery causes a lot less tissue damage than the extracapsular cataract extraction surgeries performed when I was a resident, tissue damage still occurs. That, of course, leads to the inevitable inflammatory cascade. If permitted to get out of hand, it’s a cascade that can lead not only to pain and discomfort for our patients, but to more serious problems such as cystoid macular edema.

Fortunately, we have the means to prevent these potentially vision-threatening problems from occurring. A combination of topically applied NSAIDs and steroids, used pre-, intra- and postoperatively, has shown that it will keep our surgeries relatively free of inflammation-related issues. Sufficient duration of treatment and careful monitoring are required to guard against potential complications from these drugs. Because of the daily grind of a busy practice and the “too many chefs in the kitchen” burden that comanaging with optometrists can introduce, we may tend to forget the basic tenets of targeting postoperative inflammation.

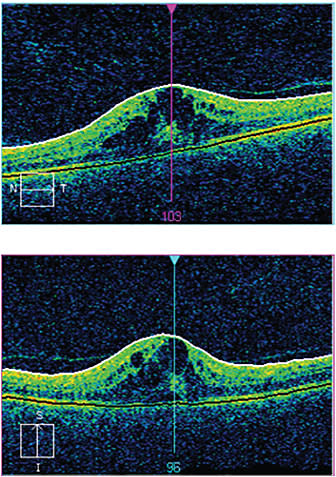

Figure 1. Six weeks after uncomplicated cataract surgery, the patient developed macular edema, as seen in the bulging cysts. His vision, which was 20/20 UCVA one week post-op, deteriorated to 20/40 UCVA manifest NI.

IMAGES COURTESY OF GREGG J. BERDY, MD

Having nonsteroidals and steroids on the surface of the eye and in the eye prior to and during surgery, and for sometime after, will stop the inflammatory response — and all its related problems — in its tracks. Here are my own pearls for protecting patients.

The inflammatory cascade

What is crucial to remember regarding inflammation is that the problem is not so much what you see, but what is happening inside the eye that you cannot see. While we can visualize the white blood cells in the anterior chamber as these cells migrate to the surgical site in response to inflammatory mediators to prevent infection, we cannot see the contents these cells release. What pours forth are the products of additional inflammatory mediators, such as prostaglandins, interleukins, leukotrienes, TNF-α and TGF-β. These molecules in turn trigger a cascade of intracellular and extracellular changes, including the breakdown of intercellular junctions, which increases vascular permeability.

One particularly significant and worrisome inflammatory cascade is the arachidonic acid pathway. Surgical trauma results in the breakdown of cell membrane phospholipids, which phospholipase A2 converts into arachidonic acid. This acid is converted into prostaglandins and leukotrienes, both inflammatory mediators. The side effects of leukotrienes and prostaglandins are pain, inflammation, macular edema and possibly increased intraocular pressure.

Steroids and NSAIDs block this dangerous cascade at two different points, making them indispensable in cataract surgery. Using them at the right time and for sufficient duration is critical.

ANTI-INFLAMMATION INSURANCE

The NSAID component

Nonsteroidal agents work downstream, inhibiting production of prostaglandins by inhibiting the cyclo-oxygenase (COX) enzyme in its two isoforms, COX-1 and COX-2. Prostaglandins also act as mediators to constrict pupils.

NSAIDs address both problems, alleviating pain and keeping the pupil dilated throughout surgery. I start patients on NSAIDs two days before surgery. However, nonsteroidals are helpful not only in the short term, but the long term as well — if you look at the complication that surgeons are most concerned about, it is cystoid macular edema (CME). CME typically develops four to six weeks after cataract surgery. It would take that long for this low-grade inflammation, if it were not being addressed, to reach the retina and build up enough inflammatory stimulus. If patients continue using the NSAIDs (as well as the steroids) for four weeks, they should be safe from developing CME.

For those patients at higher risk of developing CME — those with AMD, diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, retinal vein occlusions, surface wrinkling retinopathy — I prescribe nonsteroidals for six to eight weeks postoperatively.

The steroid component

The second anti-inflammatory weapon in a cataract surgeon’s armamentarium, of course, is a steroid drop. Back in the extracap day, the large incisions and many stitches the procedure required meant we prescribed steroids every two hours for two weeks and tapered to four times per day for an additional four weeks in order to address the inflammation caused by the tissue damage. When, thankfully we moved on to small-incision cataract surgery with far less trauma and far less inflammation, it allowed us to decrease steroid use to three or four times a day for three to four weeks postoperatively. Initially prednisone acetate was our only option, but now we can use Lotemax (loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic suspension, Bausch + Lomb) or Durezol (difluprednate Ophthalmic Emulsion, Alcon). These are the three steroid products that surgeons typically use.

Branded vs. generic drugs: Is there really still a debate?

The corneal melting scare of the late ‘90s is a big reason I prefer branded NSAIDs to their generic counterparts, but it is by no means the only reason. (http://tinyurl.com/pgp6c28) If I can use any product less often with the same or better results, I’m happy. All generic NSAIDs are dosed q.i.d., but branded NSAIDs deliver the convenience and efficacy I favor in only one or two doses per day. The once-a-day NSAIDs show good ocular penetration to the ciliary body, aqueous and retinal tissue.

Another reason I prefer branded NSAIDs is that you don’t know what the bioavailability of the drug is with a generic medication. I want to know that the medication that I am prescribing has been studied and has performed well in FDA trials. When someone says, “I’m using the generic because it’s the same drug in a different bottle,” that is incorrect: The generic drug, strictly speaking, is not the same thing as the branded drug. It may have the same concentration of the drug, but other components in the bottle may be, and probably are, different, such as the pH or the preservatives.

To me, it’s a big misconception that generics are equal to branded drugs. That holds true for branded topical steroids as well. While some generics may be equally as effective — such as some oral antibiotics, or in ophthalmology some of the beta blockers, like timolol maleate — others aren’t, in my experience. So until it’s demonstrated in a head-to-head test that a generic drug is as effective as the branded, I would advise physicians to remain skeptical.

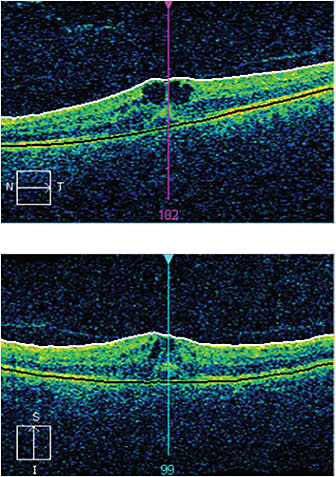

Figure 2. After three weeks of treatment with an NSAID and a steroid, the cysts are smaller.

Some surgeons choose to begin the steroid drops preoperatively. I see no problem with that. I know of surgeons who start the steroids two days before surgery, and others who start them one week before; they believe this “pre-loading” results in quieter eyes — it makes sense to try and blunt the inflammatory response.

But beginning steroids the day of surgery is simply the way I have always done it, and I have not had any problems with controlling postoperative inflammation.

Potential problems

The big worry we have about steroid use for post-op inflammation regards what it can do to intraocular pressure. To prevent IOP from rising, some surgeons will prescribe the steroid drops q.i.d. only for the first two weeks after surgery, then taper to b.id. for one week, then only once a day for the remaining week. I personally do not feel this taper is necessary. A major reason I like Lotemax Gel 0.5% (loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic gel, Bausch + Lomb), is that it was formulated not to cause a rise in intraocular pressure as compared to other potent steroids. So it’s a little safer in that respect.1

Another reason I do not worry unduly over pressure rises is that we see our patients postoperatively. It’s not as if we say to the patient, “OK, I’ll see you in six weeks.” We see our patients one day, one week and three weeks after surgery. If a pressure rise occurs, it will do so usually in two to four weeks, so we can catch it. Should the patient’s IOP rise, we reduce the frequency of the steroid and treat appropriately with IOP-lowering agents.

When to prolong treatment

At the end of four weeks, I assess the patient. If I see that the patient has a higher risk for developing macular edema or if intraocular inflammation still persists (which is very uncommon), I will prescribe both the steroid and the NSAID for another four weeks. I feel a longer course of treatment for both drugs is better than a shorter course. I’d rather go longer and if the patient does well, we can cut it off earlier, than prescribe a shorter course and find all of a sudden you’ve missed your window and the patient develops macular edema.

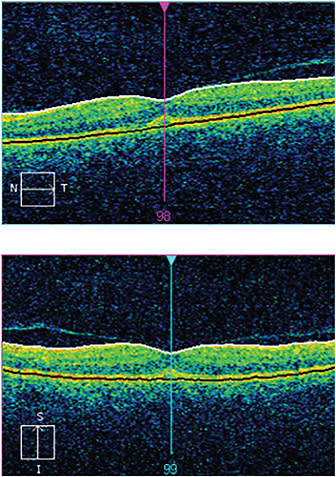

Figure 3. Twelve weeks post-op and five weeks after treatment began, the swelling is gone and the retina salvaged. The patient’s vision is 20/20 UCVA.

A word on antibiotics

The other medicine that nearly all surgeons use, although it’s very controversial, is an antibiotic. The reason for the controversy is that there have been no studies performed looking at whether antibiotics help protect against intraocular infection, endophthalmitis.

Yet most of us add the antibiotic to our postoperative anti-inflammatory regimen. I dose it for two days prior to surgery and for one week postoperatively, as most infections, if they occur, will do so in the first two or three days.

Used together, these three types of drugs will keep your patients from the dangers of postoperative inflammation, and you free from worry. OM

REFERENCE

1. Coffey MJ, DeCory HH, Lane SS. Development of a non-settling gel formulation of 0.5% loteprednol etabonate for anti-inflammatory use as an ophthalmic drop. Clin Ophthalmol. 2013;7:299–312.

About the Author | |

| Gregg J. Berdy, MD, is an assistant professor of clinical ophthalmology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis. He’s in private practice in St. Louis, specializing in corneal and external disease.

|