Bleb needling an Ex-press glaucoma shunt

A procedure to revive a scarred bleb.

By Yara Catoira-Boyle, MD

| About the Author |

|

Yara P. Catoira-Boyle, MD, is Associate Professor of Clinical Ophthalmology at the Eugene and Marilyn Glick Eye Institute, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis. Disclosure: Dr. Catoira-Boyle has received honoraria from Alcon for lecturing on use of the Ex-press shunt. Her e-mail is ycatoira@iupui.edu. |

|---|

Authors have described the needling procedure with the injection of mitomycin C (MMC) to extend the effectiveness of traditional trabeculectomy surgery since the mid-1990s. Publications since then describe the procedure as most commonly performed at the slit lamp in the office, but sometimes done in the operating room.

This procedure can be used in the early or late postoperative period, whenever the clinician feels filtration is not adequate, leading to IOP above the target. Clinical evaluation usually reveals a high, encapsulated bleb, but at times a low or flat bleb may be present. The success of bleb needling varies widely in the literature, from 28% to 92%, depending on success criteria, choice of 5-FU or MMC, and follow-up length. 1-4.

NEEDLING THE EX-PRESS BLEB

First experience was a success

Since the advent of the Ex-press shunt (Alcon, Fort Worth, Texas), many ophthalmologists have seen blebs that, similarly to trabeculectomy blebs, work well for some period of time but fail at some point. This usually leads to IOP above target and a bleb that looks lower or encapsulated and usually more vascularized. Glaucoma surgeons familiar with needling trabeculectomy blebs may then decide to needle the Ex-press shunt bleb. Or do they?

I first saw a bleb needling done at the slit lamp by my mentor, Maurice Luntz, MD, in New York. The wealth of his experience with glaucoma surgery is well known. I thought the procedure looked easy enough and if it avoided a trip to the operating room to reopen the filter or perform a new one, it made perfect sense.

My first try at it was during fellowship in one of the resident clinics at the Manhattan Eye, Ear & Throat Institute. From what I recall, the residents were gathered around me trying to see what I was doing, and it worked! The bleb elevated and the pressure went down right there. For how long? I have no idea.

Risks do exist

During my years in practice, I have performed the procedure countless times, sometimes to reopen filters I placed, other times, to reopen filters other surgeons had placed years before. I feel it is a great procedure. It basically works – but not all of the time. Is it generally safe, but all the possible risks of initial filtering surgery, including hypotony, can follow a bleb needling.

I used to perform Ex-press bleb needling at the slit lamp or in the minor procedure room at the office, just as my mentor did. Currently, in my university practice I will perform it rarely in the minor procedure room but never at the slit lamp. I basically don’t think it works very well at the slit lamp in my hands. For me, the slit lamp does not allow the needed maneuvering of the needle and it can hinder patient cooperation.

I don’t think it is fair to ask a patient to “look down while I put this needle into your eye and move it around, okay?” I will use the minor procedure room for patients who want to avoid the trip to the OR due to cost concerns, or who do not want to be sedated – usually elderly patients. I still need to schedule those in advance to allow ordering the MMC. At the VA hospital, I do them exclusively in the OR. And I think that has refined my technique, which I will now describe for needling an Ex-press shunt bleb. I will also provide some examples of cases.

Case 1We first evaluated a 65-year-old African-American man with chronic angle-closure glaucoma, worse in the right eye, in March 2009. Over the following 12 months, the patient underwent maximal medical therapy (including pilocarpine), laser iridotomy and SLT, but IOP was still 22 mm Hg and visual fields were worsening. Despite visual acuity of 20/25, we discussed phaco/IOL/Ex-press shunt/MMC due to narrow angles. We operated on the right eye in June 2010 with MMC (0.2 mg/ml) for five minutes and two permanent and two releasable sutures because we were concerned about a thick Tenon’s capsule that would prohibit laser suture lysis.

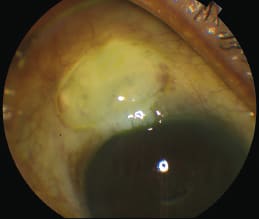

Figure 1. The patient’s right eye. Visual acuity was 20/25 uncorrected both eyes and IOP was 13 both eyes. Right eye on timolol qam and left eye on timolol, brimonidine, dorzolamide, pilocarpine and travaprost. The patient’s IOP decreased to 7 mm Hg on postoperative day one, but had risen to 17 mm Hg one month later despite releasing sutures and one 5-FU injection. He developed a high myopic and astigmatic shift after the 5-FU that later resolved, but I decided not to repeat the injection. In July 2010, IOP was 21 mm Hg. We performed bleb needling in the minor procedure room with 0.2 ml injection of 0.4 mg/ml MMC. IOP was 5 mm Hg immediately after. The IOP stayed in the single digits for one month but it was 19 mm Hg seven weeks later. I injected 0.2 ml of 0.2 mg/ml MMC in the office one more time and continued prednisolone acetate 1% drops and massage for four more months on slow taper. IOP stabilized between 12 and 13 mm Hg on timolol QAM only over the last 30 months. I last saw him in mid-September of this year when we obtained photos (Figure 1). |

PREOPERATIVE DECISION-MAKING

Assessing the patient

Naturally, the discussion and recommendation to patients about proceeding with reopening their drain is a very careful one. For me, it usually starts with “Unfortunately, your drain is not working as well as we would like.”

Most of the time, I have restarted patients on the full medical therapy they were on prior to the initial Ex-press shunt with mitomycin C, adding one drop at a time. But one reason these patients needed a filter in the first place is because they could not tolerate any eye drops. These patients are more concerning, because, as you know, if the needling does not work, you will have to repeat it or place a second filter.

If the IOP goes up within three months of the first surgery, it is considered an early failure; that by itself is a risk factor for failure of the needling. In those cases, the IOP target was recently established, and if medical therapy is not an option or did not bring IOP close to target, bleb needling is a viable option to discuss with the patient.

If the filtering had been working and IOP had been controlled but is now elevated, I will repeat a Humphrey (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, Calif.) visual field test before recommending needling. The need to lower IOP should always come from noted progression or the potential for very likely progression.

Specific risks of needling

The risks include bleeding, infection, failure of the procedure and need for more surgery. Another risk is vision loss from different causes, including worsening of a cataract, and complications from hypotony. Regarding bleeding, no consensus exists on the management of blood thinners perioperatively for glaucoma surgery.

My approach is to clear this with the primary-care physician (PCP) or cardiologist. I usually start by asking patients if they have stopped their blood thinner for other procedures recently. The next step is to contact the physician managing the blood thinners, which include aspirin, warfarin, Plavix (clopridogrel, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Princeton, N.J.) and now Pradaxa (dabigatran, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ingelheim, Germany).

While the effect of aspirin and warfarin can be measured with blood tests, that is not the case with the newer anti-platelet medications. It is a good idea to standardize the approach, such as having a form to fax to the PCP or cardiologist asking for recommendations. Naturally, avoiding myocardial infarction and strokes takes precedence over vision. Hypotony can happen, and the prior postoperative course after the initial surgery may give you a hint of what the likely outcome will be after the bleb needling.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Bleb needling: first steps

Once the patient signs the informed consent, she or he is taken to the operating room. I warn the patient that I will inject the mitomycin C prior to performing the peribulbar block. That is because I request that the patient look down so I can inject the MMC posterior to the bleb and minimize the chances of it penetrating the eye through the Ex-press shunt.

While the patient is being hooked up to the monitors and tucked in the bed, and the IV line is started, we begin topical instillation of tetracaine drops or viscous gel. When the anesthesiologist is ready to sedate the patient for the block, but before she or he does so, we ask the patient to look down as far as possible. I hold the patient’s lid up and inject 0.15 to 0.25 ml of MMC at a concentration of 0.2 mg/ml. As I am finishing the injection, I ask the anesthesiologist to initiate the sedation and follow with the block.

Performing the procedure

After the usual prep with betadine and draping, I insert a lid speculum. Then, I pass a traction suture through the cornea just anterior to the bleb. This suture is key, as I use it to move the eye as needed. I do not secure it to the drapes. I use an 8-0 vycril on spatula needle.

When I identify the bleb and flap area, I infraduct the eye with my traction suture and a 27-gauge needle that I bend at about 120 degrees with the syringe. The needle enters the subconjunctival space as far as possible, usually 8-10 mm posterior to the limbus. I proceed forward with the needle and puncture the scar around the bleb. I then perform to and fro movements of back and forth multiple times, slowly moving the needle sideways as I do this.

The goal is multiple punctures that then connect and open a large hole on the scar. I will advance the needle toward the flap and lift it up, even with poor visualization. I can lift my needle from the eye surface, keeping the tip flat or down with attention not to perforate the conjunctiva. I do this whenever I need to see where the needle tip is relation to the entry point and the bleb. I then close the puncture sites with 8-0 vycril on a BV needle, using just one suture.

Case 2We first evaluated a 79-year-old African-American man in January 2008. He complained of persistent blurry vision in the right eye after cataract extraction/IOL at another clinic in 2003. He had end-stage glaucoma, IOP was 20 mm Hg and cup-to-disc ratio was 0.9. He had dense superior and inferior arcuate defects.

Figure 2. The second patient’s right eye showing the bleb three weeks after bleb needling. Visual acuity was 20/25, IOP 13 mm Hg, massaged down to 10 mm Hg with bleb growth. We continued prednisolone drops at six times a day for another three weeks until the next follow-up. We implanted an Ex-press shunt with 0.2 mg/ml MMC for four minutes in June 2008 after the patient responded poorly to maximal medical therapy (MMT) and SLT. IOP remained stable between 9 and 11 mm Hg for almost four years, then in April 2012 IOP was 13 mm Hg. Stepwise medical therapy was initiated. In July 2012 IOP was 21 mm Hg despite MMT, the bleb was avascular and cystic with a ring of steel around it. We scheduled bleb needling in the OR for late August 2013. Bleeding was significant but not excessive. IOP was 11 mm Hg on postoperative day one, but elevated to 14 mm Hg at one week. YAG laser to the tip lowered IOP to 7 mm Hg. (Figure 2). |

Dealing with bleeding

The biggest enemy of success here is bleeding. At times, it can’t be avoided. But I recommend paying close attention to every single blood vessel to avoid puncturing any of them. I will repeat this with two more entries, usually, for a maximum of three – typically, one nasal, one temporal and one directly behind the bleb.

If bleeding becomes excessive and you lose visibility, you must stop the procedure. At times, blood will fill the bleb and even enter the eye. I inject 1 ml of subconjunctival dexamethasone posterior to the bleb, again by using the traction suture to infraduct the eye. I treat the eye with maxitrol ointment and atropine as well if the eye is phakic. Then I patch the eye.

POSTOPERATIVE COURSE

Follow-up

I see the patient on postoperative day one, and weeks 1, 3 and 5, 8 and 12, unless complications arise. I initiate prednisolone acetate 1% drops along with the antibiotic of choice in drops and maxitrol and atropine ointment at bedtime (if the patient is phakic).

Initially, I may prescribe prednisolone as often as every 1-2 hours. Most of the time, I want the patient to use it 4-6 times a day. Each week I see the patient, I will taper it by one time per day only. If the IOP starts to rise again, I am more liberal about restarting the patient’s glaucoma drops if possible. This is because there are no flap sutures to remove or cut, and I will not inject 5-FU or mitomycin in the office after bleb needlings.

Results of Ex-press needling

We are in the process of evaluating our results formally. Our preliminary data indicate that the results are encouraging. It seems these blebs can be needled just as well as trabeculectomy blebs, even though the anterior chamber cannot be entered with the needle.

I have encountered situations where, after bleb needling and initial success in elevating the bleb and lowering the IOP, the bleb becomes lower during the early postoperative period. On two occasions, I used the YAG laser to the tip of the Ex-press shunt, successfully dislodging clots that I presume were inflammatory in nature. Both patients had combined bleb needling with phacoemulsification cataract surgery and IOL implantation. OM

REFERENCES

1. Greenfield DS, Miller MP, Suner IJ, Palmberg PF. Needle elevation of the scleral flap for failing filtration blebs after trabeculectomy with mitomycin C. Am J Ophthalmol 1996;122:195-204.

2. Shin DH, Juzych MS, Khatana AK, Swendris RP, Parrow KA. Needling revision of failed filtering blebs with adjunctive 5-fluorouracil. Ophthalmic Surg 1993;24:242-248.

3. Shin DH, Kim YY, Ginde SY, et al. Risk factors for failure of 5-fluorouracil needling revision for failed conjunctival filtration blebs. Am J Ophthalmol 2001;132:875-880.

4. Anand, N, Khan, A. Long-term outcomes of needle revision of trabeculectomy blebs with mitomycin C and 5-fluorouracil. J Glaucoma 2009;18:513-520.