Current Perspectives on Corneal Antibiotics and Anti-inflammatory Agents

New medications aim to provide improved efficacy, safety and comfort for patients.

BY JOHN D. SHEPPARD, MD, MMSc

As we battle infection and inflammation, not only do we rely heavily on medications that we have known and trusted for years, but we also scan the horizon for what’s next. What new drug might work better or faster, might fight resistant bacteria, or might be safer or more comfortable for our patients?

We have reason for optimism when it comes to anti-inflammatory agents and their delivery pathways. We typically see several new drugs on the horizon every year. This growth is changing outcomes for sight-threatening conditions, such as uveitis, and fostering greater comfort and faster control in everyday applications.

The horizon is markedly less sunny for antibiotics. A recent report showed the last new systemic antibiotic was approved nearly 3 years ago, and there’s an alarming scarcity of new antibiotics in development, despite the rapid and widespread growth of antibiotic resistance.1 This divergence is already shaping how we treat infection. The trend is likely to continue, which means we must always be adaptable in our approach.

The Road to Resistance

Bacterial keratitis always posed a challenge for us. Patients seem to acquire infections at the most inopportune times, causing plenty of disruption to their daily lives. Years ago, we followed a standard protocol of combined fortified aminoglycoside and cephalosporin — both highly insoluble, both significantly toxic. Patients were miserable. The highly concentrated topical drugs were generally effective in treating the problem, but there was a chance they could make it worse through delayed healing.

Then a succession of new drugs appeared. FDA approval of ofloxacin (Ocuflox, Allergan), ciprofloxacin (Ciloxan, Alcon) and levofloxacin (Quixin, Vistakon) specifically for keratitis enabled us to treat most bacterial keratitis cases successfully with monotherpy. Treatment for bacterial keratitis became safer, more reliable and more comfortable. Today, newer, expanded-spectrum fluoroquinolones provide yet another option and an especially good choice for non-severe, peripheral, non-sight-threatening infections when corneal cultures test negative. These advanced-generation fluoroquinolones include moxifloxacin (Vigamox, Alcon) and gatifloxacin (Zymaxid, Allergan), as well as the chlorofluoro-quinolone besifloxacin (Besivance, Bausch + Lomb).

Whenever monotherapy failures occurred, we knew we were dealing with ever more common occurrences of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Staphylococcus epidermidis (MRSE). Unfortunately, more than 50% of the gram-positive cases in my practice are resistant bacteria. Gramnegative bacteria associated with contact lensrelated keratitis don’t show as much resistance, but we still must be careful with those cases, obtaining cultures whenever the prospect of treatment failure or high-risk demographics loom.

We have to monitor keratitis cases more carefully for resistance-driven treatment failure when patients have risk factors, which include previous resistance, debilitating systemic disease, recurrent infections, repeated or incomplete antibiotic therapy, immune deficiency or chronic ocular surface disease. Patients who reside in nursing homes or work in healthcare environments also face somewhat greater risk, although community-based resistance is rising rapidly as well.

When infection is resistant to standard monotherapy, the next step is to start patients on topical besifloxacin. This monotherapeutic agent performs extremely well against methicillin-resistant strains, because it has good access and longevity on the surface and more than the necessary penetration. The drug is up to 8 minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) dilutions better than other available fluoroquinolones when used against multi-drug resistant organisms. Structurally, it’s less prone to resistance mutations due to balanced activity against bacterial DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV. In addition, because it will never be used systemically in humans, or in animal husbandry, the drug is less likely to develop resistance.

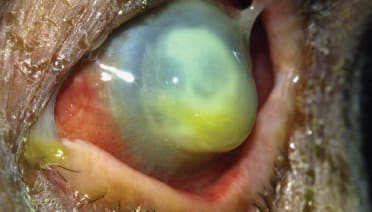

Figure 1. Severe Candida fungal keratitis in the graft host interface inducing allograft rejection.

Atypical – and Feared – Infections

Available antibiotics offer ammunition against common bacterial infections and, increasingly, against resistant strains, and we also have agents to address the less common but more fearsome ocular infections. For example, when patients present with recalcitrant keratitis related to contact lens wear, we may be looking at Acanthamoeba infection. Serious and difficult to treat, Acanthamoeba can be differentiated from other infections through unique clinical signs such as radial neurokeratitis, a diagnostic corneal scraping or use of a confocal microscope.

When we evaluate the medications that are best suited for Acanthamoeba infections, a combination of two drugs is generally most effective. Our options include a range of antiseptics and disinfectants such as polyhexamethylene biguanide (PHMB), hexamidine, chlorhexidine, polyaminopropyl biguanide (PAPB) and propamidine isethionate. Aminoglycosides, particularly neosporin (Neosporin Ophthalmic, Pfizer), are good antibiotic options. Prescribing one drug from each of two or three anti-parasitic drug classes promotes synergy and minimizes cumulative toxicity, in the same manner we combine anti-hypertensive agents for glaucoma or chemotherapeutic agents for cancer.

Another uncommon infection, fungal keratitis, has several drug treatment options. Unfortunately, when clinicians approach infection and related inflammation without a specific diagnosis, the steroids often prescribed in combination with antibiotics actually encourage fungal growth. Thus, we often recognize that the infection is fungal after we have iatrogenically exacerbated the problem with steroids. We therefore must confirm the etiologic agent of severe or unresponsive keratitis with corneal scraping.

Once established, particularly in the posterior cornea or sclera, fungal keratitis requires months of therapy with antimicrobial agents. The only approved antimicrobial agent for fungal keratitis is still natamycin (Natacyn, Alcon), which is very viscous and irritating to the eye. Some physicians are moving toward voriconazole (Vfend, Pfizer), an oral medication, which is a broad-spectrum agent against filamentous and non-filamentous fungi whose efficacy is similar to natamycin.2 Some physicians prefer voriconazole for fusarium infections, although recent evidence suggests otherwise.3 Oral fluconazole (Diflucan, Pfizer) 100 mg orally QD is prescribed by many corneal specialists for severe fungal infections, particularly when neovascular, scleral or deep corneal tissue involvement occurs. Amphotericin B (Fungizone, Bristol-Myers Squibb) can be injected directly into corneal lesions, often markedly accelerating recovery.

Finally, for patients with herpetic disease, topical ganciclovir gel (Zirgan, Bausch + Lomb) is now available in the United States. Used for more than 15 years in Europe, the drug is a remarkable development for corneal specialists, comprehensive eyecare providers and emergency room physicians. We now have a superior, more comfortable, thimerosol-free, more soluble, less toxic and more specific agent for herpetic keratitis that doesn’t require refrigeration.

Anti-inflammatory Advances

While development of new antibiotics is a slow process, we can usually count on a few new anti-inflammatory drugs every year.

We’ve been very excited by the addition of difluprednate (Durezol, Alcon), a very potent steroid molecule originally developed in Japan for dermatological use. Effective for cases of severe inflammation, this is an extremely potent drug for the entire eye. In fact, where prednisolone acetate (Pred Forte, Allergan) used to be the standard for potency, the new gold standard is difluprednate.

We use difluprednate following routine or emergency surgery and cases of severe trauma. It offers us a reliable option for cases at high risk for postoperative corneal inflammation, including patients with Fuchs’ dystrophy as well as corneal transplant patients undergoing cataract extraction. In our experience, the drug has a salutary effect on posterior uveitis and macular edema. The drug is available in a BAK-free emulsion, preserved instead with sorbitol.

Figure 2. Necrotizing pseudomonas keratits in contact lens user pending imminent perforation.

Another addition to our list of topical anti-inflammatory options is the gel formulation of loteprednol etabonate (Lotemax, Bausch + Lomb), which I’ve found to be very versatile. Loteprednol suspension has long been a mainstay for routine post-operative inflammation, chronic inflammation with maintenance therapy, and ocular surface disease. The gel formulation is less toxic, thanks to its lower concentration of BAK moisturizers and its sustained delivery to the ocular surface. A completely BAK-free ointment is now available as well.

For patients with uveitis, expect to see new systemic ant-inflammatories becoming available. In fact, thanks to the advent of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, we’ve seen a complete shift in the trajectory of the disease. For example, when children have severe juvenile arthritis and uveitis, the problem can be diagnosed early and treated with TNF inhibitors such as etanercept (Enbrel, Immunex) or infliximab (Remicade, Janssen Biotech), to help patients avoid developing complications such as diminished vision, limited range of motion due to joint damage and growth delays caused by the underlying systemic disease.

And as effective as these drugs are against uveitis, more exciting medications are in the pipeline. Although infliximab requires intravenous infusions, adalimumab (Humira, AbbVie) is administered subcutaneously every other week, a marked lifestyle improvement for chronic patients. Adalimumab is indicated only for systemic diseases, but an ongoing trial by Abbvie may provide sufficient evidence for a uveitis indication. This will enhance access for previously underserved patients. A newer TNF agent under investigation, gevokizumab (XOMA 052, XOMA), requires only monthly subcutaneous administration, yet another improvement through pharmaceutical research.

What Comes Next?

How will we battle infection and inflammation 5 years from now? Surely, we’ll still be using many of the same safe and effective options we use today. Fortunately, we can also look forward to promising new alternatives that may be more effective or better tolerated.

Riboflavin-enhanced ultraviolet corneal cross-linking is a fascinating possibility for fighting keratitis because it sterilizes the cornea. Early pilot trials have been encouraging if not overwhelmingly convincing, but we’ll need to see a first round of prospective, randomized, multi-center trials before we know if this therapy is truly effective for corneal or scleral infections.

I’m also excited by the continuous line of better medications for endogenous uveitis. Although a calcineurin inhibitor called voclosporin (VCS, ISA247, Isotechnika) failed to replicate its first phase 3 trial, additional anti-inflammatory systemic medications are in the pipeline. Sustained-release implants such as the 30-month fluocinolone (Retisert, Bausch+Lomb) pars plana device and the dexamethasone (Ozurdex, Allergan) injectable implant provide patients with long-acting control well beyond the expected duration of a triamcinolone acetonide injectable suspension (Triesence, Alcon) or periocular injection of triamcinolone acetonide.

An exciting delivery method marks another potential advance in anti-inflammatory therapy. In the future, patients with uveitis may be treated with charged dexamethasone phosphate to the eye with a 3-minute contact device treatment instead of with prolonged multi-dose prednisolone acetate therapy. The steroid molecules are charged and delivered with a low current through a contact lens-like device, reaching the deep tissues of the eye. There is no increase in IOP, presumably because all of the drug reaches the glucocorticoid receptors (GCRs) without triggering mechanisms that increase IOP. In two clinical trials with dexamethasone phosphate, primary end points were achieved.4 Researchers are just scraping the surface of this technology.

Although we don’t anticipate a major, imminent breakthrough in ophthalmic antibiotics, we’re all working strategically to deal with resistance. The contrast is stark. We observe epidemic emerging antibiotic resistance without a pipeline for common ocular surface infections and the prevention of infection in millions of ocular surgeries. On the other hand, we embrace numerous new drugs and delivery platforms for orphan ocular inflammatory diseases such as non-infectious posterior uveitis, acknowledging the contributions these advances make for our ubiquitous surgical candidates. ■

References

1. Boucher HW, Talbot GH, Benjamin DK, et al. 10 × ‘20 Progress—development of new drugs active against gram-negative bacilli: An update from the infectious diseases society of America. Clin Infect Dis. First published online: April 17, 2013. Available at: http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2013/04/16/cid.cit152.full

2. Prajna NV, Mascarenhas J, Krishnan T, et al. Comparison of natamycin and voriconazole for the treatment of fungal keratitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(6):672-678.

3. Prajna, NV, Krishnan T, Mascarenhas, J, et al. The mycotic ulcer treatment trial: A randomized trial comparing natamycin vs voriconazole. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131(4):422-429.

4. EyeGate’s EGP-437 Matches the Standard-of-Cares Response Rate in Phase III Study in Patients with Anterior Uveitis. Press release. EyeGate Pharma, April 09, 2013. Available at: http:// www.eyegatepharma.com/pdf/news2013/EyegatePR_Uveitis_TopLineData_08apr_Final.pdf

|

John D. Sheppard, MD, MMSc, is President of Virginia Eye Consultants, located in Norfolk and Hampton, Va., and Clinical Director of the Lee Center for Ocular Pharmacology at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk. |