Addressing patients' low vision needs

The general ophthalmologist should have a strong handle on helping these patients function better.

By Janet S. Sunness, MD

| About the Author | |

|---|---|

|

Janet S. Sunness, MD, is medical director of the Richard E. Hoover Low Vision Rehabilitation Services at the Greater Baltimore Medical Center. She reports no financial interests in products mentioned in this article. Her e-mail is jsunness@gbmc.org. Disclosure: Dr. Sunness has no relationships to disclose. |

Ophthalmology has not historically operated along a rehabilitation model. For example, if a patient breaks a hip, she or he will automatically receive crutches and a referral physical therapy by the orthopedist.

When we have patients with poor vision, the same automatic referral for low vision rehabilitation often does not occur.1 This is particularly true for patients who have moderate visual loss. These patients may have needs related to work or daily activities, and these needs will not be addressed unless they are recognized and acted upon.

In this article, I will address a few issues related to low vision rehabilitation. I have taken some of this material from the American Academy of Ophthalmology's SmartSight program2 and the Preferred Practice Pattern for vision rehabilitation.3 The SmartSight section on the Academy's Web site includes a handout for patients, with a listing of a number of low vision resources.

RECOGNIZE THE NEED

Patients who require low vision intervention

Patients who are legally blind — with VA in the better eye of 20/200 or worse and/or a visual field less than 20º in diameter — are clearly in need of low vision services. But most patients who would benefit from low vision services are not in this severe category.4

Here are several examples of patients who would benefit, along with the ICD9 codes for visual impairment. All services would be covered for low vision rehabilitation services by the ophthalmologist or optometrist and by the occupational therapist, according to current CMS guidelines.

- VA 20/70 or worse in better eye — the definition of moderate visual impairment under Medicare (369.25).

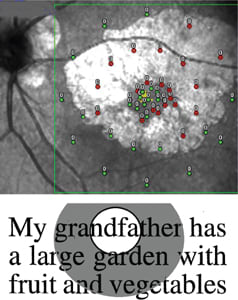

- VA 20/25- with a central scotoma (coded as 368.41) (Figure 1). This patient has advanced dry AMD and a ring of scotoma surrounding a spared foveal area. The visual acuity is good for single letters, but the patient has difficulty seeing words or faces, because the whole word or face does not “fit” in the seeing area surrounded by a blind area.

Figure 1. This patient has VA of 20/25- in each eye, with a ring of geographic atrophy and corresponding dense scotoma surrounding the seeing foveal region. The OPTOS microperimetry image (top) shows in green the retinal locations that saw the brightest (0dB) stimulus. The red donuts are the sites where the brightest stimulus was not seen. When this patient viewed the text shown (bottom: 20/125 size for the testing distance used) and fixated on the “d” in “grandfather,” she could only see “ndfa” without moving her eye. She has a similar picture in the fellow eye.

- VA 20/20 with a left homonymous hemianopia from a stroke (coded as 368.46). The patient has difficulty with mobility and also with reading because he or she cannot identify where a line of text starts.

- VA 20/40 with a visual field constricted to 30º from diabetic retinopathy or glaucoma (coded as 368.45): The patient may bump into things, have difficulty crossing streets and have similar issues.

Time-consuming evaluation

The rehabilitation approach is geared toward understanding patients' goals for visual tasks and determining how to help them using a variety of interventions.

Nothing is magical about what a low vision professional does. The general ophthalmologist can perform the low vision evaluation and much of the treatment, but it is time-intensive.

If the general ophthalmologist or retinal specialist does not wish to do the low vision evaluation when a need arises, the ethical obligation would be to refer the patient for these services.

ANTI-VEGF THERAPY AND LOW VISION

Aiding patients with wet AMD

From a rehabilitation perspective, anti-VEGF treatment puts the patient in an optimal situation for low vision intervention. The median VA in treated patients in many trials is around 20/70, meaning the patient needs letters 3.5 times larger than a patient with 20/20 does to see clearly. Patients with VA worse than 20/40 typically need an add greater than +2.50 to read. In addition, patients with AMD generally need more task lighting.

Every few weeks, we have a patient with wet AMD on anti-VEGF treatment and VA around 20/50 or 20/60 come to our low vision service who has not been reading in several years. With some tweaking — increasing the reading add to +4.00 and improving lighting — the patient typically is back to reading fairly comfortably. You can increase the add to +4.50 without a need for a prism; you just have to tell the patient that she or he will have to hold things closer, and you may have to supply an intermediate add in the form of a trifocal if you go over a +3.50 add.

Factors in referral

Several factors may explain why patients on anti-VEGF treatment with low vision needs do not get referrals for low vision rehabilitation.5 The visual acuity is so much better than in the past, and the retina specialist is focused on getting the person to return very frequently to monitor and manage the choroidal neovascularization.

Many patients may take a number of months to improve, and the physician may assume that the patient will improve still further (but in the meantime, the patient cannot read). In addition, today, with anti-VEGF treatment, we often do not see the ugly scars that we frequently saw in the past, and a patient can have a dense scotoma without any obvious scarring (Figure 2).

Figure 2. This patient with choroidal neovascularization is on anti-VEGF treatment. Fluid and lipid are present, but no scar or atrophy are obvious. Nonetheless, the patient has a dense scotoma, outlined in black. The image is from a Nidek MP1. The solid red squares show where the patient saw the brightest (0dB) stimulus. The unfilled red squares are where the patient did not see the brightest stimulus. The small blue dots show the variation in fixation during microperimetry testing.

The treating physician should recognize that many AMD patients have difficulty with reading and other tasks, despite good VA, and should make it a habit to refer them for low vision intervention if necessary.

MAINSTREAM DEVICES

Kindles, flashlights and more

With advancements in technology, many devices designed for and used by normally sighted people are of immense help for the low vision patient, particularly the patient with moderate visual loss or with the need for increased contrast.6

The Kindle (Amazon.com, Seattle) and iPad (Apple, Cupertino, Calif.) allow for adjusting the character size for reading books and other materials, for having the device read the material to you and for displaying the text as black on white, white on black (reverse contrast, very useful in patients sensitive to glare) or in a variety of color combinations.

Patients can also use the iPad and the iPhone (Apple) as portable video magnifiers; they can take a picture of an article or a phone number and then enlarge it to read it. Many apps are available to magnify more easily or to read text that has been imaged. The iPhone has Siri, an app to specify what you want by voice and to dictate texts or e-mails.

Many elderly people, whether normal-sighted or with low vision, use these devices, so age is not a barrier. The devices significantly enhance the patient's life, and they are unobtrusive and not as expensive as customized low vision video devices.

While Medicare covers the physician's and the occupational therapist's services, it does not cover low vision devices, so cost of a device is a significant issue.

Lighting and enhanced contrast

In patients with advanced dry AMD (geographic atrophy), VA drops by an average of 5 lines when viewing the ETDRS chart wearing a filter like a moderate sunglass (vs. 2 lines in a patient who has only drusen and no advanced AMD).7

Patients with AMD typically have great difficulty in dim environments, such as restaurants. A portable, battery-powered table light can be helpful, as can a flashlight or a low-power illuminated magnifier.

Serving dark food on a light plate can enhance contrast, as can marking the edges of steps with tape. Puff paint or adhesive “bumps” can mark a microwave so the patient can operate it more readily.

A signature guide or check guide is often helpful. Large-print bold checks are generally available for ordering, and a bold pen can offer a significant improvement. These interventions may be enough for some patients to improve their ability to perform daily activities.

In a rehabilitation model, the important consideration is whether the patient can now perform these activities. If she or he still cannot, referral for assessment for magnifiers and other interventions is indicated.

CONCLUSION

When the ophthalmologist displays increased sensitivity to a patient's needs, he or she can obtain low vision rehabilitation services and resume most daily activities more easily. Whether the ophthalmologist wants to undertake a low vision evaluation and treatment or refer the patient to someone else is a matter of personal choice, but ideally obtaining these services for patients should be a reflex response to their needs. OM

| Visual hallucinations are common in patients with AMD |

|---|

|

Charles Bonnet Syndrome, or visual hallucinations, occurs in about 20% of patients with AMD.1 It is important for patients to know about this, but obviously one must ask about this with sensitivity. I try to ask about it with every AMD patient I see for low vision evaluation, especially in the presence of other family members. This what I typically say to be nonthreatening: “Now I am going to ask you something, because I want you to know about it even if you don't have it. About one out of five patients with AMD and some decreased vision get what we call visual hallucinations. They see things that are not there. They can be people, patterns, flowers, etc. Does that ever happen to you?” Here are some of the responses I have heard from my patients:

Before I ask a patient about visual hallucinations, I try to guess whether the patient has them. I find I cannot predict who has them; they occur in people with only moderate visual loss and are independent of education and other factors. It is worthwhile to send a letter to the patients' primary care physicians and let them know about the presence of visual hallucinations as well. REFERENCE1. Holroyd S, Rabins PV, Finkelstein D, et al. Visual hallucinations in patients with macular degeneration. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:1701-1706. |

REFERENCES

1. Hoover RE. The ophthalmologist's role in new rehabilitation patterns. Arch Ophthalmol. 1967;78:664-675.

2. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Guidelines: SmartSight/Low Vision. Available at:

3. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Vision Rehabilitation PPP – September 2012. Available at:

4. Goldstein JE, Massof RW, Deremeik JT, et al; LOVRNET Study Group. Baseline traits of low vision patients served by private outpatient clinical centers in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130:1028-1037.

5. Sunness JS, Schartz RB, Thompson JT, Sjaarda RN, Elman MJ. Patterns of referral of retinal patients for low vision intervention in the anti-VEGF era. Retina. 2009;29:1036-1039.

6. Sunness JS. Mainstream technology for the visually impaired patient with macular disease. Retin Physician. 2013;10(1):TK.

7. Sunness JS, Rubin GS, Applegate CA, et al. Visual function abnormalities and prognosis in eyes with age-related geographic atrophy of the macula and good visual acuity. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:1677-1691.