The Brave New World of Premium Pricing

Experts say the technology is finally up to snuff. But are cataract patients willing to pay out-of-pocket fees?

By A. James Khodabakhsh, MD

Premium pricing is tricky for a physician to contemplate. As the ophthalmic community gains more advanced technological developments, we can offer safer, more effective treatments to our patients. The downside? Using those advancements cost money, and insurers are not inclined to pay for “lifestyle” benefits. Recently, the realm of cataract surgery has grown to include a hybrid of retail and medicine—something that was always the case with refractive surgery, where patients expected to pay out of pocket, but is an entirely new phenomenon for cataracts.

While there are many patients who expect healthcare services to be affordable, and would naturally prefer third-party coverage, there are also many more than you might think who are willing to invest in the quality of life improvements now possible. Following a few guidelines will help increase your upgrade rate and make the most of the premium market.

Talking the Talk

Let's take a typical cataract patient. When the patient comes into my office, he or she fills out the typical paperwork and a questionnaire about visual quality and expectations in real-world scenarios. My technicians perform autorefraction, topography and IOLMaster measurements, then take a full history, check the vision and pressure and dilate the patient.

Once dilated, the patient sees me. After a complete exam and diagnosis of cataract (it is important that there is no other cause of vision loss), I present the lens choices. It is important for the surgeon to note that there are no “good” or “inferior” lenses. I always present monofocal lenses as a good option—I never put them down in an attempt to upsell the patient to a premium. Rather, I explain that “regular” lenses are monofocal but will serve the patient well. Depending on the measurements, amount of astigmatism, personality, occupation, refractive status and patient needs, I go over the premium lenses. The differences are laid out, whether it's astigmatism correction and not needing glasses at a distance or multifocality and accommodation.

The most important point in presenting premium procedures that cost extra to the patient is never to feel like you are “selling” them something. If the patient senses sales pressure, the doctor will not only lose the procedure, but also lose the patient—which equals lost revenue. This is a fact. Through the system I use to speak with my patients, I have almost an 80% upgrade rate to premium lenses. The patients love that I spend more time with them and that they hear explanations from a doctor rather than a sales person. I always tell patients upfront that the newer lenses cost money out of pocket.

Cost is a part of the entire presentation because it is intricately involved with implanting premium lenses. I do explain to patients that these lenses cost more because they offer more than a monofocal lens. If the patient asks for a more detailed explanation of the costs, I clarify that the cost is related to the extra measurements and time it takes to implant the lens as well as the astigmatism control and newer technology of the lenses.

Package Deal

Both my surgical coordinator and I make the patient aware that premium lenses require a series of extra tests that add to the cost, including refraction, manual and auto Ks, topography, wavefront aberrometry, IOL Master, OCT of the macula, lens calculations and astigmatism control. I perform all of them on premium patients. Some surgeons charge a la carte for these elements, but we present these as a package deal with all premium lens procedures. The more information we have, the better we as doctors can serve our patients' needs. Additionally, we bundle in postoperative care, which may include laser vision correction.

We also recently added a femtosecond laser for cataract surgery to our practice; however, we will not charge for femto cataract surgery by itself. As mandated by CMS, surgeons cannot bill for “laser cataract surgery,” only its refractive component. In the future, we will bundle this with our premium lenses as the preliminary results have been surprisingly good.

We still don't have hard data to prove that all newer technology is better. Will femtosecond lasers decrease endothelial cell loss? Will our end results have better refractive outcomes? We still don't know, but so far all data points to cleaner and more efficient surgery using this new technology. For the most part, my patients do not inquire about hard data. However, my second office is very close to the Boeing and Northrup Grumman plants, so I do have a large population of engineers and high level technically-inclined patients who come in with lists of questions and their own research. They often pull up articles from peer-reviewed journals or blog entries from doctors across the country as a way to figure out which procedure was best for them. The best way to approach these patients is to tell them exactly what you know—don't hold back.

Cataract surgery has essentially become refractive surgery. Like the boom days of laser vision correction, surgeons have to believe in the procedure, package it well, do it right and be able to handle the many potential postoperative issues. However, unlike the golden days of LASIK where, even at its height, there was only a 4% market penetration, the current patient base of baby boomers offer a tremendous opportunity. These patients are willing to spend money to “see young” just like they want to “look young” with plastic surgery. In essence, they want to be free of glasses. Surgeons have to understand that 100% of their patients could develop cataracts of some kind—they already are surgical candidates, with huge potential.

That distinction bears reiteration. LASIK patients choose a surgical alternative; premium cataract patients choose an alternative surgery. In other words, LASIK is entirely avoidable for anyone who's squeamish about surgery—just wear corrective lenses. Cataract surgery, however, is a near inevitability for almost everyone. In that context, the discussion with a cataract patient about premium options seems much more liberating to me: “You're going to have surgery, Mrs. Jones, now let's make sure you're aware of all the options and have the chance to tailor the procedure to your lifestyle.”

For the most part, today's aging population is different than previous generations, who would have been more satisfied with standard monofocal implants and using glasses for the rest of their life. Nowadays, the boomers don't want to be old. These patients are still active, working and don't want to be dependent on spectacles. As a result, they are willing to spend the extra money to gain this freedom. While today's economic climate may change spending habits, generally the boomer generation isn't afraid to spend money on their vision.

Maintaining Integrity

Confidence and honesty are key to having a successful premium practice. Depending on the lens, we charge about $2000 to $5000 extra per eye. These extra costs cover both the preoperative measurements and intraoperative procedures and measurements, including LRIs and the Orange intraoperative wavefront aberrometer. This adds a tremendous amount of revenue to our practice—the kind of extra money that runs the risk of encouraging some surgeons to push the pricey lenses as much as possible. It's crucial for doctors with high-volume premium practices to maintain integrity. I get second opinions all the time from patients who are unhappy with their premium lenses because the IOL was likely chosen by a doctor who was more concerned about the cost than picking the perfect lens for the patient's vision needs. There are some physicians in the community who are putting premium lenses in as many patients as they can, regardless of their suitability, and it's wrong.

Doctors have to be careful with these lenses. I do not implant premium IOLs in people with preexisting ocular pathology like advanced glaucoma, corneal scarring, macular degeneration or other retinal concerns. In these situations, not only will the lenses not work but they also may make the patient's vision deteriorate further than before the operation. If the surgeon does not put premium lenses in the best candidate, his premium market is going to quickly die down. For the most part, patients are pretty computer and internet savvy and have so much access to information nowadays. The patients will ultimately know if you their surgeon has an ulterior motive. Bad clinical decisions and poor results will absolutely lead to future loss of business.

Because of the revenue potential, doctors now have extra incentive to implant premium intraocular lenses, so on a deeper level they are more prone to push those lenses. There is nothing wrong with making more money, but the cliché applies: the patient's safety (and results) have to be our number one priority.

What the Future Holds

I think there is a “dark cloud” hanging over medicine. With the changing nature of finances in the healthcare industry, there is a very real potential for Medicare cuts and a significant decrease in reimbursements. Unfortunately, practice costs will continue to increase. Rent goes up every year, and new equipment costs and employee salaries are on the rise. We have to find new sources of revenue not linked to insurance companies.

Commerce and medicine will continue to blend over the next few years, with premium channels providing our practices with needed sources of income, and our patients with more options than ever before. OM

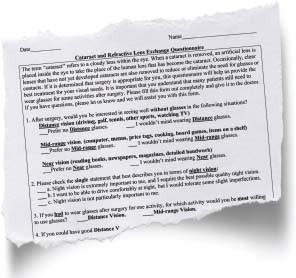

| Ask the Right Questions With the Dell Survey |

|---|

If long you want your patients to be happy with their IOL selection in the run, you need to have a thorough understanding of their lifestyle, day-to-day needs and expectations concerning procedural outcomes. It's no secret that when patients are shelling out for premium lenses, they expect to have perfect vision immediately and to never have to wear glasses again. Steven Dell, MD, created the Dell Survey to identify unrealistic expectations. By asking patients about when they would be most willing to wear glasses after surgery (reading, computer or driving), the survey subtly informs them that, realistically, there are inherent compromises to the procedure. The survey also asks about the importance of distance versus near vision without glasses, experiencing halos in exchange for good daytime distance vision and nighttime near vision, and the patient's personality (ranging from easy going to perfectionist). The survey makes it easy to note where expectations have gotten out of reach. Knowing exactly what your patient believes the procedure will provide can aid your conversation and steer them back on track if expectations have gone astray. Incorporate the Dell Survey into your cataract workup to help present realistic information about procedural outcomes and make it clear that 100% perfect vision isn't plausible. You—and your patients—will be glad you did. |

|

A. James Khodabakhsh, MD, is an anterior segment specialist in Beverly Hills, Ca., and assistant clinical professor of ophthalmology at New York medical college. He lectures on anterior segment disease, with his main focus on lens implant surgery. He is a consultant and speaker to AMO, Bausch + Lomb and Ista. You can e-mail him at lasereyedoc@aol.com. |