The Case for Gonioscopy

It may seem old-school, but it remains our most effective way to diagnose angle closure glaucoma.

By Jody Piltz-Seymour, MD

We have all heard that an aging population, both in the United States and abroad, will soon result in a daunting increase in age-related eye diseases. This is certainly no exaggeration in the case of glaucoma. It is estimated that between 2005 and 2025, the population in India and China who are over the age of 65 will double;1 similarly, the US population over age 65 will increase from 40 million in 2010 to 89 million people in 2050.2

Angle-closure glaucoma will become especially problematic. While this condition is less prevalent than primary open-angle glaucoma, a much higher proportion of angle-closure patients are blind. In 2000, an estimated 6.7 million people worldwide were blind due to primary glaucoma; fully half that number had angle-closure glaucoma.3 If most angle-closure glaucoma cases were of the acute variety, we clinicians would have less to worry about; no ophthalmologist is going to miss the diagnosis of acute angle-closure glaucoma. But most people who develop angle-closure glaucoma never have an acute attack — they develop angle closure slowly and insidiously. Many are in fact misdiagnosed with open-angle glaucoma.

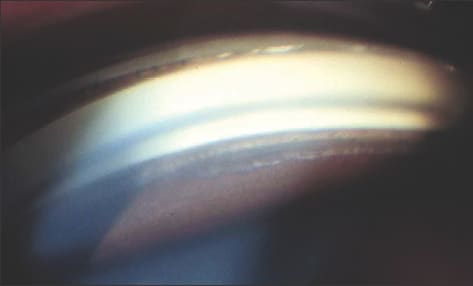

Figure 1. Angle recession is commonly overlooked in the absence of a gonioscopic exam. IMAGE COURTESY OF JODY PILTZ-SEYMOUR, MD.

The biggest obstacle to diagnosing angle-closure glaucoma is failure to examine the angle. Gonioscopy is the best solution to detecting angle-closure glaucoma as early as possible. Iridotomy in high-risk individuals can often prevent development of peripheral anterior synechiae (PAS), avoiding the development of elevated IOP. Undiagnosed, the development of permanent PAS results in chronic angle-closure glaucoma with marked IOP elevation that is difficult to control medically. Iridotomy cannot undo PAS and thus cannot lower the IOP once extensive PAS have developed.

If gonioscopy is not performed, chronic angle-closure glaucoma patients present with increasing IOP that mimics primary open-angle glaucoma. And in this era of sophisticated imaging technologies, gonioscopy is becoming something of a lost art. In this article, I will make the case for why it remains an effective diagnostic weapon and offer guidelines in becoming proficient with the procedure.

Poster Child for Gonioscopy

A rather dramatic case I had illustrates why gonioscopy remains so important in diagnosing and treating glaucoma. A 50-year-old Caucasian female had a nine-year history of intractable headache, worse on the left side. For the last three years her headaches had been associated with foggy vision lasting 10 minutes that resolved spontaneously, and she was told that she had migraines. She had been seen by her medical doctor, by a neurologist and intermittently by an ophthalmologist. Her intraocular pressure was always normal in the office. No gonioscopy was performed, and the fundus exam just said “Normal DMVP.”

After nine years of unremarkable ocular exams, the patient was sent to a neuro-ophthalmologist; he noted a high IOP OS. She was referred to me for glaucoma evaluation. I found VA was 20/20 OU, afferent pupillary defect OS, and IOP was 19 OD, 33 OS. Gonioscopy revealed narrow angles OU with extensive PAS in the left eye worse than the right eye (OD: B to C10S, OS with synechial closure for 270 degrees, appositional closure of the remaining angle. The left optic nerve had extensive rim loss.

The history and exam suggested a long history of symptomatic subacute angle-closure glaucoma with intermittent episodes of elevated IOP causing headache and smokey vision, leading to glaucomatous optic nerve damage, early visual field loss and permanent synechial angle closure. She progressed from intermittent subacute angle-closure glaucoma to chronic angle-closure glaucoma. Again, this diagnosis was only made after the IOP became permanently elevated.

Wouldn't it have been nice if we could have caught this before she developed permanent glaucoma in the left eye? Had gonioscopy been performed earlier, her narrow angles would have been detected and iridotomy could have prevented development of permanent chronic angle-closure glaucoma. She was stable for four years on topical therapy, but eventually needed trabeculectomy on the left to control IOP.

Our goal as clinicians is to diagnose angle-closure glaucoma before IOP elevation becomes permanent. Gonioscopy enables us to diagnose angle closure and help prevent intermittent angle closure from turning into the chronic form.

Why Not Iridotomies for All?

So why don't ophthalmologists skip gonioscopy and just do iridotomies on any patient who may seem to have narrow anterior chambers on slit lamp examination? We must always be mindful of the injunction to “do no harm.” While iridotomies may seem fairly innocuous, this procedure can have implications for vision and ocular health, and thus iridotomy should only be performed when indicated.

Ophthalmologists need an effective strategy to distinguish people who need iridotomies from those who do not. Slit-lamp evaluation without gonioscopy is inadequate in detecting narrow angles. Plateau iris, where there is crowding of the peripheral iris with a deep central chamber, will be missed. The slit lamp also cannot distinguish moderately narrow angles that can be followed without iridotomy from potentially occludable angles that do require iridotomy.

In some patients, iridotomy is more difficult to perform. This is especially true in one of the highest-risk populations: patients of Chinese ancestry. Because the Chinese often have thick, fuzzy brown irides, more laser pulses and higher power levels are often required to establish a patent iridotomy. With the increased energy, there is concern that there may be an increased risk of uveitis, endothelial damage, elevated IOP or an increase in the risk of cataracts. If you even slightly increase the risk of cataracts in a procedure that's done globally and in a developing country, you run the risk of increasing the risk of visual impairment if this population does not have easy access to cataract surgery.

What About Imaging Devices?

Comprehensive ophthalmologists may wonder if the many cutting-edge imaging devices that have come our way in recent years could be used rather than going to the effort of learning (or relearning) how to perform gonioscopy. Certainly imaging devices do offer many attractive benefits: they produce beautiful images, and the technician does the exam for you. Also, they offer precise quantification of results and excellent documentation for the patient's chart.

On its side of the ledger, gonioscopy offers many significant advantages that are absent from imaging devices:

► Provides views of the entire angle, not just cross sections.

► Allows visualization of: pigmentation in the angle; neovascularization; PAS; tumors in the angle; hemorrhages, keratic precipitates and foreign bodies; blood in Schlemn's canal; iris processes; bumpy peripheral iris, often a sign of iris cysts; double hump of plateau iris; extent of angle recession; posterior embryotoxon and other congenital anomalies.

► Helps the clinician to differentiate appositional from synechial angle closure.

► Helps the physician gain facility with angle evaluation needed when performing angle surgery.

► Allows the clinician to see the dynamics with his or her own eyes: light vs. dark, with and without compression, etc.

Additionally, gonioscopy offers two more things we can all appreciate: access and convenience. With the gonio lens in your pocket, you can perform gonioscopy whenever needed. If you have to send everyone off for an angle image and you're not sure if you're going to get reimbursed, or if you have the staff to do it, you may not get the information you need on all of your patients.

Use angle imaging, if it is available, as an ancillary test.

Gonioscopy Guidelines

For better diagnoses, identify and screen high-risk groups with history and risk factor assessment, and perform a complete eye exam on everyone. That includes gonioscopy and optic nerve evaluation. And don't discriminate — don't perform gonioscopy only on hyperopes or people of Asian ancestry, because anyone can get angle-closure glaucoma.

As I always remind residents, remember that a gonio lens is a simple mirror. It's not like your fundus lenses, where images are inverted and backwards. Keep your gonio lens close at hand, because if you have to search for it every time you want to do gonioscopy, you will end up not doing it.

Once you become proficient in gonioscopy, it can be done very quickly. Here are some tips on the basics:

Direct gonioscopy is done with the Koeppe lens; it is mainly used in the operating room for examinations under anesthesia on children. You probably won't need to concern yourself too much with that.

Indirect gonioscopy is what can be so instrumental in helping you diagnose angle-closure glaucoma. For indirect gonioscopy, we use the Goldmann or a four-mirror lens.

■ Non-Compressive Gonioscopy: The Goldmann lens provides excellent optics and is a wonderful help to learn angle landmarks. It also helps us become proficient with laser procedures. A viscous coupling solution is required and the angle cannot be pressed open with this lens. Therefore, while the Goldmann lens is excellent to learn gonioscopy with, it can be inconvenient to use and cannot help distinguish appositional from synechial angle closure.

■ Compressive gonioscopy. Four-mirror lenses don't require a coupling solution and can be easily placed on and off the eye during the slit lamp exam. When you become proficient in gonioscopy, the entire examination can take just seconds, yet can be a vital part of the ocular examination, even during busy clinic hours.

By allowing pressure to be placed on the cornea, the angle can be examined with compression and without compression, enabling us to distinguish whether there's appositional or synechial angle closure. However, you must be aware of when you are compressing to avoid artificially deepening the angle.

Starting Out

It is easiest to learn the anatomical landmarks with the Goldmann lens; it offers a clearer view than the four-mirror lenses. Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose solution makes the lens more stable. However, for everyday gonioscopy, a four-mirror lens is indispensable. It should be kept in a convenient location (if you keep it in your pocket, it is always available!) and used on every patient. If it is difficult to see structures, instruct the patient to look towards the mirror.

It is helpful to use the corneal light wedge to help identify landmarks. Shine a very thin beam of light and look where the anterior and posterior beams come together. The two beams meet at Schwalbe's line. If the two beams join together as the light dips into the iris, you know that there is angle closure. The corneal wedge can also help in distinguishing a pale angle from a closed angle.

One of the most important recommendations I can make about gonioscopy is to do it in both bright and dim illumination. It's important to use bright light first. Identify the landmarks and see everything you can possibly see. Then make the beam very short to get the light out of the pupil and as dim as possible to see what happens to the angle as the pupil dilates. It is wonderful to watch the dynamic changes in the angle between bright and dim illumination (Figures 2a and 2b). You pick up many angle closure patients by viewing the angle in dim light. Some people have widely open angles in bright light, but impressive angle narrowing in dim light.

Figures 2a and 2b. It is crucial to perform gonioscopy in both bright (left) and dim lights. Watch what happens to the angle in dim light. This is when you can find many angle closures.

It is also important to re-check the angle with and without compression. Observe the angle first by lightly touching the lens to the eye, then pressing to see if you can deepen the angle. Look for permanent PAS or the classic double hump sign of plateau iris.

Additionally, you should always check the angle superiorly. Inferior angles often have more pigmentation than superior angles, including more prominent pigmentation of Schwalbe's line. The pigmented Schwalbe's line is called Sampaolesi's line and is always more pronounced in the inferior angle. Sometimes, a pigmented Sampaolesi's line can be confused with trabecular meshwork, so you should always check the angle superiorly — you are much less likely to have pigment on Schwalbe's line, and this can help with identifying the correct landmarks (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3. Pigmented Schwalbe's line, also called Sampaolesi's line.

Figure 4. It is crucial to check the angle superiorly, as you are much less likely to have pigment on Schwalbe's line.

A Note on Documentation

I find it important to use a classification system as I perform gonioscopy to define the angles for documentation and communication. Classic systems include the Scheie and Schaeffer systems. The Scheie system ranks angles on a scale of 0 to 4 depending on angle structures visible, with 0 indicating a wide-open angle and 4 indicating a closed angle. The Shaffer system has been used more commonly. It also ranks angles on a scale of 0 to 4, but it uses angular width and classifies deep angles as a 4 and closed angles as a 0.

I prefer the Spaeth classification because it defines the angle using multiple components and avoids the confusion between the Scheie and Schaeffer systems. Spaeth categorizes the angle width in degrees, the location of the iris insertion and the curvature of the peripheral iris. The level of iris insertion is given a letter rating between A and E:

(A) Anterior to Schwalbe's line.

(B) Anterior to the posterior edge of the trabecular meshwork.

(C) Posterior to scleral spur.

(D) Insertion into ciliary body.

(E) Insertion into deep CB band.

The level of iris insertion is measured both pre- and post-compression. The angular width is recorded in degrees. The peripheral iris curvature is listed as b for bowed, f for flat, c for concave or p for plateau. D40f is an angle wide open to ciliary body with a 40 degree width and a flat insertion. C5b is a narrow angle with an iris insertion posterior to scleral spur, but a very narrow angular width with anterior bowing of the peripheral iris.

Too Valuable to Let Languish

Gonioscopy offers us far too much information about the anterior drainage angle to let it become a lost art. By being critical to diagnosing angle-closure glaucoma, we can avoid the blindness that is much more likely in angle-closure than in open-angle glaucoma. This is particularly important when considering that most primary angle-closure glaucoma does not present with an acute episode. Most angle closure develops insidiously and asymptomatically. Only by identifying high-risk angles can we prevent this potentially blinding form of glaucoma.

If our four-mirror gonioscope is handy, we always have the needed tools to combat angle-closure glaucoma. Our newer anterior segment imaging technology offers wonderful information, but at this time nothing replaces gonioscopy. I hope you will take the time to master it. OM

For further gonio education, I advise you to check out a wonderful Web site, www.gonioscopy.org, run by Wallace L.M. Alward, MD, and his book, Color Atlas of Gonioscopy.

References

1. Eberstadt N. Growing Old the Hard Way: China, Russia, India. Policy Review. April 1, 2006 no. 136. Accessed http://www.hoover.org/publications/policy-review/article/6783 at Jan. 20, 2011.

2. U.S. Census Bureau. National Population Projections Released 2008 (Based on Census 2000). www.census.gov/population/www/projections/2008projections.html. Accessed Jan. 20, 2011.

3. Quigley HA. Number of people with glaucoma worldwide. Br J Ophthal. May 1996; 80:389-93.

| Jody Piltz-Seymour, MD, is an adjunct associate professor of ophthalmology with the University of Pennsylvania Health System, and in private practice in the Philadelphia area. She can be reached at jody.seymour@hotmail.com. |