Do I Have the Right Number of Staff?

The volume-based staffing model may give you the correct answer.

By Maureen Waddle, Senior Consulant with BSM Consulting

One of the most common requests consultants receive from physicians and managers is for assistance evaluating the organization's structure in an effort to answer the question, “does our practice have the right number of employees?” Since gross wages usually account for about 25% of practice revenues, it is important to pay careful attention to this particular expense. Most physicians and managers also realize that solely considering staff members as an expense is myopic. Appropriate staff support enhances a physician's ability to generate revenue. In ophthalmic practices, as in most services, staff members are the most important asset of the organization. While recognizing that there is an additional human dynamic to consider in designing an organizational structure, this article will focus on the use of statistics and productivity to create a staff model tool that will help managers better predict staffing needs.

The Usual Staffing Benchmarks

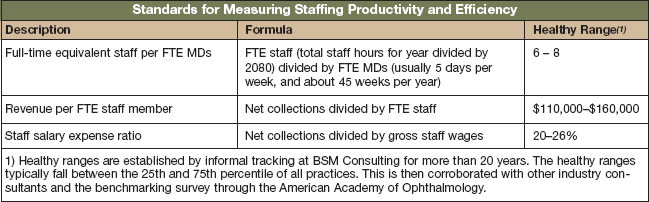

Over the years, ophthalmology practices have established certain staffing measures. Practices most commonly use the standards in the table below for measuring staffing productivity and efficiency.

When practices fall outside of the “healthy ranges,” most can find viable explanations for the variance. This is why it is important to heed a few cautions about using benchmarks:

(1) Make sure you compare apples to apples—know the definitions of the benchmarks;

(2) Use more than one benchmark to make decisions.

(3) Pay more attention to your internal trends than to national-benchmarking standards; and

(4) Remember ratios are impacted by a numerator and a denominator—consider both in making decisions about necessary changes.

… And Their Limitations

As practices monitor trends, inevitably they begin to realize there are some limitations in the standard staffing benchmarks when trying to accurately predict staffing requirements. Some of the limitations include:

■ Benchmarks measure history. While history is the best predictor of the future, if you are making significant changes to your practice—such as adding a new subspecialty, starting an optical, or creating a new service line—you do not have a model to predict staffing needs for these additions.

■ Benchmarks do not consider type of practice/type of visits or doctor's practice preference. Obviously, one cannot compare the benchmarks of a retina subspecialty practice against a general ophthalmology practice. However, there are differences within “general” ophthalmology practices that may skew benchmarks as well. Some practices are more comprehensive in nature, performing a lower volume of a wider variety of surgeries. Other specialty practices focus on cataract surgery and only provide cataract-related diagnostic tests, often turning away routine eye exams or monitoring of conditions that are unrelated to their focus. Some doctors enjoy a fast-paced environment and require more staff members to keep pace with the higher volume of patients. Some doctors prefer an environment with more support staff while others are fine (and efficient) without support. Any of these circumstances affect benchmarking results.

■ Standard benchmarks do not correlate to work units produced. Staffing models are used across industries and are typically based on a number of work units produced. If we want to accurately predict how many employees constitute the “right number” in an ophthalmic practice, we need to understand the number of people it takes to produce work units. We never really want to think of patients as work units, but if we want to create a tool that adequately predicts staffing requirements, appropriate measuring units must be identified. In ophthalmic practices, work units are best defined as number of office visits, number of diagnostic tests and number of surgeries.

A Volume-based Model Predicts Staffing Needs

Because of the limitations of benchmarking, practices still struggle to justify staffing needs, even when staffing benchmarks fall in the healthy ranges. In order to accurately predict the number of employees required to support an individual practice, create a model that is based on the number of people required to produce the number of work units the practice generates. This tool can then help forecast staffing needs as volume grows, services are added, or providers are added to the practice.

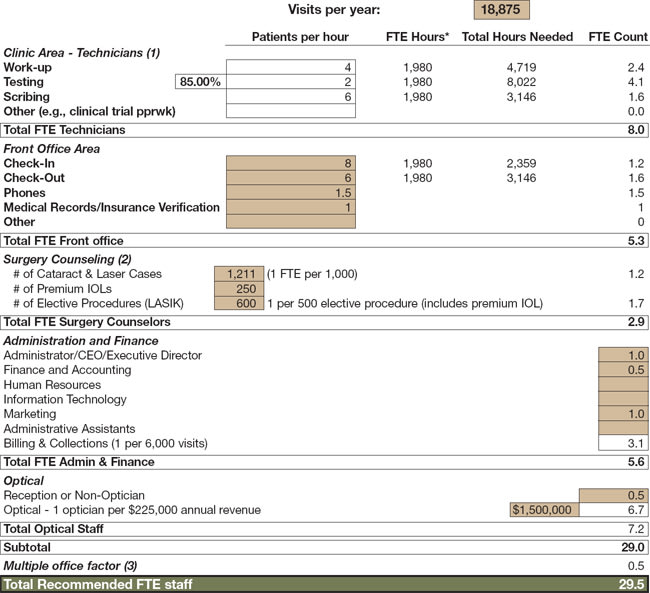

Figure 1 shows a sample of a staffing-model completed for a general ophthalmology practice. This practice includes optical and has two ophthalmologists and two optometrists. To customize this type of analysis for your practice, I've outlined the necessary steps below:

(1) Collect the following historic information for a 12-month period (either the last fiscal year or trailing 12 months):

● Results of time-flow studies that show the average work-up times per technician. If time-flow studies do not exist, estimate times based on the survey completed a few years ago by consultants Jane Shuman of Eyetechs and Derek Preece of BSM Consulting for the American Society of Ophthalmic Administrators. (The Technician Benchmarking Survey is available in the ASOA bookstore, http://shop.asoa.org/)

● Percentage of diagnostic tests performed compared to total office visits. Include only diagnostic tests that are billed separately and require at least 10 minutes of a technician's time. Since the tool is designed to predict staffing needs, do not include diagnostic tests performed by the doctor, such as extended ophthalmoscopy or gonioscopy.

● Total number of outpatient and laser surgeries performed.

● Total of cosmetic, refractive or premium IOL surgeries performed.

● Total number of office visits.

● Total net collections for optical (receipts less refunds).

● Any statistics regarding productivity for front-office and phone activities.

(2) Create a spreadsheet. Tie the formulas to the volume as much as possible, thereby automatically adjusting staff predictions when you adjust volumes. This sample tool was created in Microsoft Excel. The sample offers an idea of how to set up a similar tool.

(3) Enter the volume of office visits (include no-charge visits such as postops).

(4) Complete predictions for clinical staffing based on statistics from time-flow studies.

(5) Complete predictions for front-office services based on statistic from time-flow studies.

(6) Complete predictions for surgery counseling. This position is a hybrid of technician and front-office staff member. Typically, one person fills all functions of the role. One person can usually perform these duties for up to 1,000 combined outpatient surgeries and in-office laser procedures (cataract, glaucoma, lasers, etc.). A practice with more “cash” services, though, typically requires more time for surgical counseling. If a practice divides responsibilities differently, consider those responsibilities when predicting staffing needs. If all of the patient education is provided by the technicians, account for that within the technician section of the staff modeling. The surgery counselor then becomes more of a scheduler and should be able to handle higher volume than predicted in the example.

(7) Estimate administrative and financial functions. Though volume of office visits adds some complexity to the management of a practice, these functions are usually not necessary to “process the work unit.” Estimate these fixed services/costs based on the complexity of the practice itself in terms of number of physicians, number of locations, reporting requirements, and practice governance.

(8) Calculate accounts receivable/billing staff. Historic benchmarks suggest that one full-time equivalent billing person is necessary for every $1 million of receipts. Since that is the median of the healthy range for most general ophthalmologists, and the average for general ophthalmologists in terms of work units (number of office visits per year) is around 6,000, the sample model ties FTE-billing staff to office visits using the formula one FTE biller per 6,000 visits. This enables the number to automatically calculate with changes in volume predictions.

(9) Estimate optical needs. The standard benchmark for opticians within an ophthalmic practice is one optician per $225,000 of collections per year.

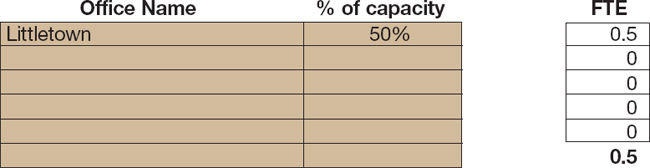

(10) Apply a factor for multiple locations. The sample staff model accounts for staffing needs based on volume and will predict the correct number of staff regardless of total number of locations. However, if a location is not functioning at capacity but requires staffing—even though there is little or no volume on certain days—this should be factored into the staffing assessment.

Figure 1. Volume-based Staffing Model

This tool is designed to help you predict staffing needs based on historic or projected volume. In categories with fixed staffing such as administrative, estimate staffing based on your practice needs. Complete the colored cells.

*Hours = 2080 hours less 2 weeks vacation and 5 miscellaneous days for SL/personal days, etc.

(1) Number per hour based on national averages and time flow studies (see ASOA's Technician Benchmarking survey).

(2) The recommendations and calculations for staffing in these areas are based on averages from studying practices nationwide. Your specific practice may vary. If so, please override the calculation and enter what you believe to be the FTE number of staff required to meet your practice needs.

(3) If satellite offices are running at, or near capacity, then the volume calculations should be sufficient to plan staffing. However, if the satellite is below capacity and requires staffing even though the office is not seeing patients, then you need to account for this staffing need. Either use your own calculation, or use the below formula for any satellite location operating at less than 75% capacity:

Courtesy of BSM ConnectionTM for Ophthalmology

Using the Results

For the person in the practice tasked with setting staff schedules, it is easy to see how useful a tool like this can be—especially when a doctor is questioning staffing assignments. Basing staff requirements on a provider's typical “work units” is an unbiased, mathematical approach.

During strategic planning processes, managers typically conduct an analysis of financial impact for strategic choices under consideration—adding a new provider, for instance. A volume-based staffing model ties to the predicted volume and more accurately predicts staffing requirements, and thus expenses. Better information leads to better decisions.

Follow-up Training

Getting the right total number of full-time equivalents is only the first step in drafting an overall organizational structure. The volume-based staffing model does give a general idea of where to deploy these resources, but the practice must also have the training systems in place to ensure staff members achieve the productivity numbers used in creating the staff model. Furthermore, practices with cohesive human resources processes tied to the vision of the practice find that productivity per person increases, thereby decreasing the total required FTEs over time.

Better Business Decisions

With gross wages accounting for a quarter of practice revenues, it's easy to understand the need to monitor the organizational structure of a practice to determine appropriate staffing. The methodology of the volume-based staffing model is based on analysis and statistics, making it an extremely reliable source of evaluation. Once collected, the productivity and volume data outlined here can be translated into work units to establish a tailor-made staff-model tool for achieving an accurate, unbiased assessment of a practice's most valuable asset: its staff. Once this tool is utilized in tandem with standard industry benchmarks, a practice will find it exceedingly valuable in making better business decisions in multiple areas of the practice. OM

|

Maureen Waddle, a senior consultant with BSM Consulting, has more than 20 years of experience managing ophthalmic practices and ambulatory surgery centers. |