The FLAP Over LASIK

Just how likely is postop ectasia? Surgeons debate the impact of a new screening tool.

BY LESLIE GOLDBERG, ASSOCIATE EDITOR

All physicians take the Hippocratic oath's admonishment "first, do no harm" to heart, but it's especially forefront in the minds of refractive surgeons, whose patients voluntarily forego no-risk spectacles and low-risk contact lenses, opting instead for an elective procedure with the potential, however small, for adverse outcomes. Given this heightened sense of responsibility, it's the surgeon's top priority to predict which corneas will be able to sustain the structural deficit LASIK creates and which won't. The ablation by necessity thins the cornea, and the flap violates its integrity; postoperatively, some are unable to withstand a rise in IOP. The result? Ectasia for the patient and a potential lawsuit for the practice.

So it was no surprise that the refractive surgical community initially welcomed the news of a potentially transformative rating system that could isolate patients at risk for post-LASIK ectasia. Some experts wonder, though, if it's too restrictive. Adopting it as the gold standard would prevent many worthwhile candidates from obtaining successful LASIK outcomes; it could also brand the current protocols used by even the top surgeons as malpractice, they worry.

Read on for an in-depth look at the relationship between ectasia and LASIK from several top surgeons.

Risky Business

Iatrogenic keratectasia was first reported by refractive surgery guru Theo Seiler, M.D., in 1998.1 Since that time, a number of case reports have identified a variety of potential risk factors, including high myopia, a residual stromal bed (RSB) thickness of less than 250 μm, low preoperative corneal thickness and forme fruste keratoconus. But ectasia can occur even in otherwise asymptomatic patients, especially younger ones.2

Hoping to integrate this array of risk factors into a systematic approach to screening, Emory's Bradley Randleman, M.D., R. Doyle Stulting, M.D. and colleagues published an ectasia risk factor weighting study early last year.2 The study compares the characteristics of eyes with ectatic corneas seen at Emory and those described in the peer-reviewed literature with a group of control eyes that experienced a normal course after LASIK.

The study concludes that postoperative ectasia, like keratoconus, most likely represents an end-stage manifestation of corneal warpage that arises from a variety of causes, including weak corneas before surgery, a residual stromal bed too low to maintain structural integrity, trauma and patients otherwise destined to develop keratoconus.2

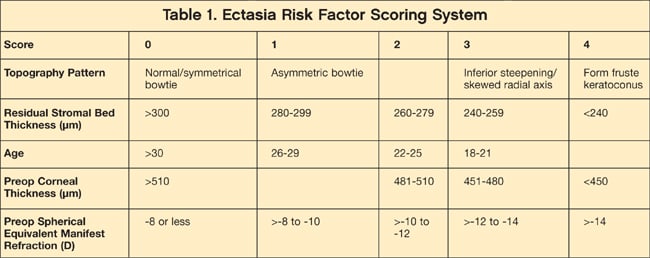

The authors developed a risk-factor stratification model taking into account and assigning a point value to the following variables, in order of significance: (1) preoperative topographic abnormalities, (2) low RSB thickness, (3) younger patient age, (4) low preoperative corneal thickness, and (5) high myopia (Table 1).2 The paper concluded that "a quantitative method can be used to identify eyes at risk for developing ectasia after LASIK that, if validated, represents a significant improvement over current screening strategies."2

Source: Randleman JB, Woodward M, Lynn MJ, et al. Risk assessment for ectasia after corneal refractive surgery. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:37-50.

The clinical implications of this study are enormous, but criticisms about the implementation of this weighting system exist. "The ophthalmology community as a whole must be aware that we cannot dogmatically apply a scoring system without careful scrutiny and, if necessary, further refinement," says John Vukich, M.D., of Madison, Wisc. He says that while the assessment tool is an important step forward, ophthalmologists need to be careful how they weigh each risk factor.

Daniel Durrie, M.D., a corneal specialist in Overland Park, Kan., concurs. "While the work is very important because it calls our attention to certain criteria, the rating system — when checked against other databases — really isn't predictive of cases that had post-LASIK ectasia. It still needs to be considered a work in progress."

Ageism

The high weight given to a patient's age is one of the biggest issues that critics have with the system. Drs. Vukich and Durrie agree that you can suppose that age is a risk factor in terms of topography, but absent topographical correlation or any other findings, age in and of itself as a single risk factor does not appear a risk factor for post-LASIK ectasia, even though this is given significant weight in the Randleman criteria. (see Table 2)

| Table 2. Scoring Recommendations on Whether or Not to Proceed With LASIK |

|---|

| 0 to 2 (Low Risk): Proceed with LASIK or surface ablation.

3 (Moderate Risk): Proceed with caution, consider special informed consent; safety of surface ablation has not been established. Consider MRSE stability, degree of astigmatism, between-eye topographic asymmetry, and family history 4 (High Risk): Do not perform LASIK; safety of surface ablation has not been established. |

Source: Randleman JB, Woodward M, Lynn MJ, et al. Risk assessment for ectasia after corneal refractive surgery. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:37-50.

Dr. Vukich says that this is the first study that weighs age on a relative scale commensurate with topography. "If you have inferior steepening or a skewed radial axis, it has the same weight in terms of risk potential as a patient who is 21 years of age with completely normal indices in every regard," he notes. "Anyone age 18 to 21 is given the risk factor of three," he says. "We know that every patient who has had LASIK was age 18 to 21 at some point in their life," he says, and the vast number of patients who have had LASIK have done very well. "Is it now appropriate to say that if they had had LASIK at a younger age, then they would have had a much higher chance of developing keratoconus?"

Others concur. "We applied their scoring criteria to more than 250 randomly selected patients who underwent LASIK who did not develop ectasia in the first postoperative year at three of our centers and found a false-positive range consistent with the 3.8% rate reported in the study," Richard Duffey, et al. wrote in a letter to the editor in the October 2008 issue of Ophthalmology.3 "However, when we applied the Ectasia Risk Factor Score System as a [screening] tool at one of our centers for all refractive candidates, we found that more than 35% of the eyes would be classified as high risk, many from patients who remained good surgical candidates in our opinion, mainly because this was a relatively young group of patients. Our raw age scores in these patients suggest that age is likely an overstated risk factor that has been assigned high point values."

The letter goes on to state, "Although Randleman et al. found that those with ectasia were significantly younger than the controls, there are no data cited in the literature or in their study to suggest the relative ectasia risk when performing LASIK on eyes in the various age categories using the Ectasia Risk Assessment Score System. Therefore, the values of risk scores assigned to various age groups in their study are arbitrary and, in our opinion, place younger eyes in a higher risk category than is warranted by the current literature."

David R. Hardten, M.D., F.A.C.S., director of Minnesota Eye Consultants' Clinical Research Department, is one of the doctors who was a co-author of the letter to the editor authored by Dr. Duffey. He states that "intuitively, the fact that there was some relationship found in the study makes sense: the younger you are, the more likely you are to have something go wrong in the rest of your lifetime, even if we don't see anything wrong with you now or find anything wrong on testing." He thinks this is inevitable, given the incidence figures. "Keratoconus also happens to be more common in younger patients," he explains. "The bigger question that is not yet answered is whether these patients are really at higher risk from the surgery itself."

| Ectasia vs. Keratoconus: The Battle of the Bulge | |

|---|---|

| Dr. Durrie has a unique take on whether or not corneal ectasia even exists. "The tendency among most corneal specialists who have studied ectasia in detail is to consider people with naturally occurring keratoconus and those with post-LASIK ectasia to be virtually indistinguishable," he says. He reasons that since the topography and histology results look the same, the patient may simply have keratoconus, which presents earlier due to having had LASIK. Dr. Durrie believes that some individuals have artificially divided these two conditions, when they are really a part of the same group. It's inevitable that a small number of LASIK patients are going to develop keratoconus, he says. "If the general population contains one in 2,000 people with a tendency toward keratoconus and those people happen to have refractive surgery — it means one in 2,000 people are going to develop keratoconus regardless of whether or not they have LASIK surgery," says Dr. Durrie. "The incidence of post-LASIK ectasia seen in large practices is relatively similar compared to the frequency of keratoconus. So, the question is — are the patients who develop ectasia genetically prone to developing it?" He does not believe that modern LASIK or PRK can cause ectasia in a normal eye. Rather, he believes that patients with post-LASIK ectasia all had eyes that were prone to keratoconus and they happened to have undergone LASIK. "I'm not saying that cutting fibers and putting a flap in a cornea wouldn't aggravate the keratoconus if a patient were genetically prone to it," states Dr. Durrie. "But, if we realize that these patients are genetically prone to keratoconus, we can treat it. I think ‘post-LASIK ectasia’ is really the wrong term and it really should be called post-LASIK keratoconous. If you can't tell the differences between the two at a cellular level, they are probably the same condition." Dr. Durrie says that patients leaving his office with a condition termed "keratoconus" instead of "ectasia" feel relieved because they are told keratoconus is a treatable disease. "I can treat keratoconus with contact lenses or with corneal cross-linking. I know how to treat it with CK and other remedies. We can treat these patients and that is the big issue," he concludes. This perspective is not shared by all. "I have never seen an estimate of keratoconus being as high as one in 2,000 people," says Dr. Randleman. "However, even if we accept that number, patients with keratoconus most frequently have some signs, such as physical findings, topographic changes, corneal thinning, etc. and these are the things we are specifically looking for and the variables we have specifically taken into account for the Ectasia Scoring System. One of the reasons someone might have fewer of these clinical signs is because they are young, which reiterates the weighting of young patient age as we have." Dr. Randleman believes that post-LASIK ectasia and keratoconus are related in that most patients who develop the former likely had a predisposition to the latter. "However, there are certainly cases that have developed in patients that otherwise had no clinical evidence of KC and had their corneas destabilized by LASIK," he concludes. | |

|

|

| These figures represent Orbscans of post-LASIK ectasia (left) and natural keratoconus (right). According to Dr. Durrie, these scans demonstrate that it is not possible to tell the diseases apart. IMAGES COURTESY OF DAN DURRIE, M.D. | |

Dr. Randleman believes his group's conclusions are supported by the data. "In brief, age was a significant factor in every statistical analysis performed and was the most significant factor discriminating ectasia cases from controls if topography was normal," he says. "The feedback we have received has been based on anecdote rather than science."

Drs. Durrie and Vukich agree that the association with age certainly should be considered but think that the importance of age relative to pachymetry or topography appears to be overstated. "Even the pachymetry is unclear as to what is the best or safest number in which you can say, ‘Here is a minimal thickness in total for a cornea before we start versus what is a minimum bed thickness,’" says Dr. Vukich. "We have been slow as a group to either adopt individual numbers — whether it be an absolute thickness of the cornea, or thinness of the residual stromal bed, as being absolute," given the heterogeneity of LASIK patient characteristics.

Weight Issues

Dr. Durrie also stresses that these criteria should not be used to make a clinical decision. "You make a decision based on all the information you have about your patient, including the issue of your patient changing over time," he says. "Rather then telling a patient ‘You aren't a candidate because you have a funny looking cornea,’ you should see them again in 6 months or a year and they may turn out to be an excellent candidate."

Could this end up as a legal tool to prosecute individuals who otherwise are practicing sound medicine? "Now all of a sudden the rules have changed as to who is a sound and appropriate candidate. This is a really important question that cannot be left unanswered," Dr. Vukich says. "We need to have more information to support these conclusions. We need corroborating evidence to support this," he says.

"This paper is very important because it is getting us to start to look at the criteria of patients who have developed this condition and then we can better educate patients who are at risk," reiterates Dr. Durrie. But he and other refractive surgeons feel that the criteria have not been tested thoroughly enough and that the weighting system, as it currently stands, is not ready to be used as a tool to measure the soundness of a LASIK candidate, nor can it be used to set medical-legal precedence. "The study took a retrospective look at a group and came up with some prospective conclusions. Now you need to use it prospectively and see if it can measure ectasia against other large databases of LASIK patients and see if it is predictive," says Dr. Durrie. "So far this hasn't happened."

More than 90% of the cases used to develop this scoring system were performed before the development of femtosecond lasers. "The thickness of the flaps that were created for these patients were done by a variety of keratomes and a variety of thicknesses and it is no surprise that this comes into play," says Dr. Vukich. In addition, the technology available today is very different than what doctors in the study used. "With consistent 110 μm flaps being made with femtosecond lasers, which represent over 50% of surgeries, are the data still as relevant? Are the minimum thicknesses of a cornea still a reasonable assumption based on data dating back 10 years or more?" he wonders, also citing recent improvements such as 3D topography that continue to provide more precise corneal assessments.

The issue at stake in this debate is how to define what constitutes a good candidate for LASIK, says Dr. Vukich. "Now that we as a profession have performed millions of LASIK surgeries, are we going to accept without further investigation that a 500 μm cornea is a 2-point risk factor, in and of itself — in an eye with no other issues?" That question needs an answer before these particular indices (risk factor points) are adopted widely as a hard and fast rule, he says. Dr. Vukich thinks this is the reason many refractive surgeons, despite their initial enthusiasm, do not use this categorization as the deciding factor. "All of that said, I applaud the effort and the academic value of looking at additional potential risk factors beyond just, like thickness and topography," he says. "I think that what Randleman has done is laudable and is a positive thing. The next step in this is refinement."

The authors are aware of these concerns and are recruiting participants to develop an ectasia registry. According to an invitation from R. Doyle Stulting, M.D., Ph.D., on the ASCRS web site, phase 1 of the project seeks to "validate known risk factors for LASIK and to discover new ones" while phase 2 "will include prospective clinical trials of LASIK in cases with preoperative characteristics that might raise concern about the development of ectasia, but have not been proven to increase the risk of developing it." To get involved or just provide feedback, contact Dr. Stulting at ophtrds@emory.edu. OM

References

- Seiler T, Koufala K, Richter G. Iatrogenic keratectasia after laser in situ keratomileusis. J Refract Surg. 1998;14:312-7. Refractive Surgery. 2000;16:368-70.

- Randleman JB, Woodward M, Lynn MJ, et al. Risk assessment for ectasia after corneal refractive surgery. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:37-50.

- Duffey R, Hardten D, Lindstrom R, Probst L, Schanzlin D, Tate G, Wexler S. Letter to the editor. Ophthalmology. 115:1849-1850.