Treating Dry Eye: An Opportunity to Build Patient Loyalty

Being up-to-date on this common malady helps your practice as well as your patients.

BY DAVID R. HARDTEN, M.D.

In ophthalmology practices, dry eye is a common presenting condition, accounting for nearly 25% of office visits1,2 — yet it remains underdiagnosed and undertreated. Until recently, this was at least partly due to treatment options being limited to temporary symptom relief and strategies to modify exacerbating lifestyle and environmental factors. Over the last 10 years, however, our improved understanding of dry eye pathophysiology has led to the development of improved treatment options. A primary example is cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsion 0.05% (Restasis, Allergan, Irvine, Calif.), indicated to help increase tear production in cases where it may be reduced as a result of chronic dry eye. Additionally, new artificial tear formulations have been developed that provide longer-lasting symptom relief of dry eye.

Thus, more than ever before, dry eye now represents an opportunity for ophthalmologists to provide patients more effective treatment, engendering greater patient satisfaction and retention. Success with dry eye can also help practices grow through treatment of frequent co-existing problems such as cataract, retinal disorders and glaucoma. It also means, however, that patient expectations are commensurately greater. In this article, I will review the current information relating to the diagnosis and treatment of dry eye and related conditions.

A Common Condition

Though dry eye is undoubtedly a common condition, there are no definitive estimates of prevalence because the few reported studies differ in how data was gathered and in diagnostic criteria used. For example, one report estimated nearly 4 in 10 Americans suffer dry eye symptoms,4 whereas another report estimated it affects approximately 20 million Americans.5 A population-based study found prevalence rates of 14% in adults 48 to 91 years old, 8% in those younger than 60, and 19% in those older than 80.6 Other studies have shown dry eye is more common in women than men, affecting more than 3.2 million American women over 50 years of age.7 In general, however, such data are probably underestimates because many people who have dry eye do not spontaneously discuss their symptoms with their healthcare provider.

The Role of Inflammation in Pathogenesis

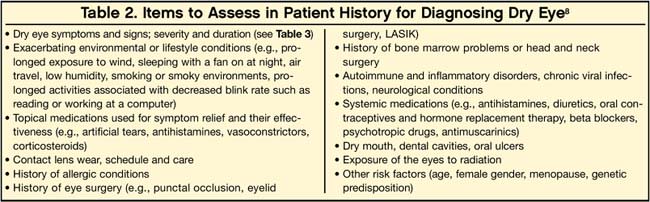

Dry eye is the result of insufficient tear production, excessive tear evaporation and/or abnormal tear composition. It can be sporadic; for example, occurring after exposure to hot, dry or windy environments; or it can be chronic as a result of ocular abnormalities. Whichever the case, dry eye can be associated with any of various patient-, environment-, and disease-related factors (Tables 1 and 2), according to the American Academy of Ophthalmology Cornea/External Disease Panel.8

Inflammation is now recognized as a key pathogenic process in tear-deficient dry eye (Sjögren’s syndrome and non-Sjögren’s). On the ocular surface, epithelial cells and lacrimal glands secrete antigenic substances that are processed and “presented” by local macrophages to effector T cells, initiating a local inflammatory immune response that is normally kept in check by regulatory T cells.9,10 However, various factors (Table 1) can interfere with regulatory T-cell activity, promoting greater inflammation. For example, reduced levels of testosterone, which occur with aging or menopause, are associated with decreased regulatory T cell activity and are a putative risk factor for dry eye.11

Once excessive inflammation begins, it can lead to a destructive, self-reinforcing process in which effector T cells secrete more inflammatory cytokines into the tear film, recruiting additional effector T cells and stimulating further inflammation, causing changes in tear quantity and/or quality.12 Over time, this process can damage the ocular surface and the tear-secreting glands, exacerbating dry eye symptoms.9,10,13,14

Our understanding of this process has spurred the development of potentially improved, targeted treatments, which I will cover later.

Diagnosing Dry Eye

As generally recommended in diagnosis and treatment guidelines from the National Eye Institute, the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) and an International Task Force (ITF) of dry eye specialists,15 dry eye should be diagnosed based on multiple assessments — including patient history, physical examination and diagnostic tests — because its symptoms can be similar to those associated with other conditions (e.g., allergies, eye strain, contact lens intolerance and other ocular surface diseases).

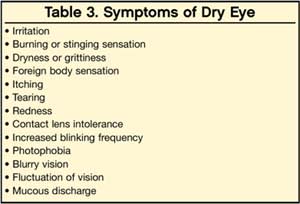

The patient history should attempt to capture the patient’s specific symptoms, as they can vary greatly (Table 3). Physicians can use standard questionnaires such as the McMonnies Dry Eye Index, the Ocular Surface Disease Index, the Dry Eye Questionnaire and the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire 25. It is important to recognize that each patient may describe the same symptom or sensation differently. Additionally, many patients with dry eye experience visual fluctuations, which is often overlooked.

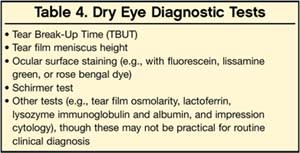

The physical examination involves assessing the patient’s visual acuity, lacrimal gland, cranial nerve function, skin, face and hands; and conducting slit-lamp biomicroscopy of the eyes and eyelids. Specific tests can help confirm a dry eye diagnosis, evaluate its severity and monitor treatment response (Table 4). I prefer lissamine green ocular staining over rose bengal as it is more comfortable for the patient and is available as densely staining, convenient individual-use strips. The Schirmer test is useful for both dry eye and blepharitis, but may vary from exam to exam and be normal to high in evaporative dry eye conditions.

Treatment

Let’s examine both what patients can do about their symptoms and the drug therapies that often follow as the condition becomes more severe.

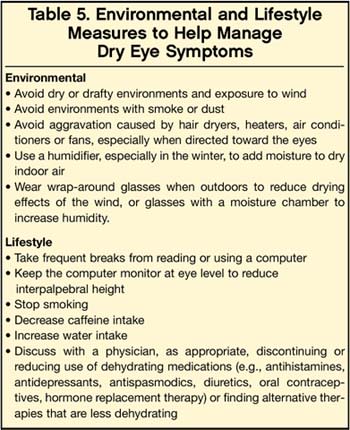

■ Patient education, environmental and lifestyle management. Dry eye is best managed through a combination of patient education, environmental control and lifestyle modification (Table 5), and appropriate therapies. Patients should be educated about dry eye and, based on their history, made aware of any of the patient-related, environmental, and disease-related factors that cause or contribute specifically to their condition. It is also important that the patient understands dry eye requires long-term management, and that he or she needs realistic treatment expectations.

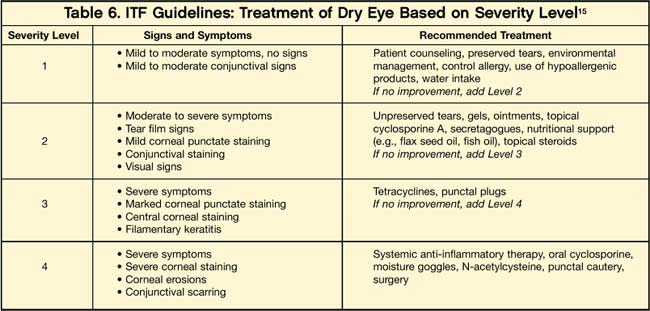

■ Dry eye therapies. Specific therapies for dry eye include artificial tears, prescription therapies and surgery. The ITF recommends artificial tears as a starting point, and adding other therapies as needed based on symptom severity (Table 6).15 I have found these guidelines to be of value, though they are somewhat conservative as to when to start treatment. In practice, eyecare professionals often deal with the question of when to start treatment and who decides — the physician or the patient? Some patients are very uncomfortable with even minimal symptoms, whereas others accept more severe symptoms. I believe the best approach is for the doctor to discuss with the patient and come to a joint decision.

Even at the first level of therapy (artificial tears), the doctor can help patients find the most appropriate product among the many available over-the-counter. For example, eyedrops that merely reduce redness are generally not appropriate over the long term because they contain vasoconstrictors that can damage the ocular surface.

From a practice standpoint, I have begun using Optive (Allergan), which contains not only carboxymethylcellulose (CMC), but also the compatible solutes glycerine, L-carnitine and erythritol. CMC provides hydration and lubrication to the eye and has been shown to bind to corneal epithelial cell surfaces and remain bound for several hours. The compatible solutes in Optive lubricate the surface of the eye and penetrate below the surface to provide osmoprotection to the corneal epithelial cells from excessive salt levels, which lead to increasing signs and symptoms of dry eye.16 Other examples of compatible solutes include various amino acids, polyols, sugars and methylamines.17 There are a variety of other artificial tear products available that contain surface lubricants such as CMC (TheraTears, Advanced Vision Research) and hypromellose (Genteal Mild, Novartis); and others that contain a compatible solute such as glycerin (Advanced Eye Relief, Bausch & Lomb) or a polyol (Systane, Alcon). However, few contain both surface lubricants and compatible solutes (e.g., Tears Naturale Forte, Tears Naturale) contains hypromellose and glycerin; Visine Pure Tears Portables (Johnson & Johnson) contains glycerin, hypromellose and polyethylene glycol). Optive is also one of the few that contains both of these functional ingredients, and the only one formulated with CMC and the compatible solutes of glycerin, L-carnitine and erythritol.

For many patients, it is important to convey how prophylactic use of artificial tears can be more effective than using them “after the fact” of experiencing symptoms. I often use the analogy of using hand lotion — it works better if used to prevent chapping and cracking than after these develop, at which point the lotion will probably sting.

| As a rule of thumb,I recommend that if the patient uses artificial tears three or more times a day without sufficient relief, the physician should consider additional therapies. |

As a rule of thumb, I recommend that if the patient uses artificial tears three or more times a day without sufficient relief, the physician should consider additional therapies. Additionally, artificial tears alone are of minimal benefit with blepharitis, as they merely rinse debris from the eye into eyelids, resulting in a rapid return of symptoms.

When artificial tears are not enough, I usually add Restasis as the next level of therapy. The medication reduces the common underlying cause of inflammation and increases the eyes’ ability to produce tears. This is generally consistent with ITF guidelines, which recommend prescription therapies for dry eye severity level two or greater. Other therapies include:

- Antibiotics (oral doxycycline or erythromycin or topical erythromycin), to reduce inflammation and improve lipid production, particularly in dry eye due to excess tear evaporation

Oral cholinergic agonists (pilocarpine and cevimeline), especially in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome, though these medications appear to be more effective in treating dry mouth and can be associated with significant systemic side effects

- Topical corticosteroids, though severe side effects are associated with long-term use

- N-acetylcysteine eye drops to help dissolve mucous plaques that can occur in more severe cases of dry eye.18

Other therapies, such as punctal occlusion or plugs and surgery (e.g., tear duct cauterization or, in very severe cases, tarsorrhaphy), are usually performed when medical treatments are not sufficiently effective.

Eyecare professionals need to follow up with patients to assess their response to therapy and the need to change it, to monitor for ocular structural damage and provide reassurance. The frequency of visits will depend not only on the severity of the problem, but also on the patient need for guidance during therapy. Patient visits may occur anywhere as frequently as every few weeks during initial therapy for a severe problem, or as infrequently as every 2 years for patients with stable mild disease.

Opportunity X 3

Dry eye is a common condition in ophthalmology practice. New and improved therapies are available, representing an opportunity for eyecare professionals to provide patients more effective treatment, increase patient satisfaction and retention, and expand.

References

1. Hikichi T, Yoshida A, Fukui Y, et. al. Prevalence of dry eye in Japanese eye centers. Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1995;233:555–558.

2. Doughty MJ, Fonn D, Richter D, et. al. A patient questionnaire approach to estimating the prevalence of dry eye symptoms in patient presenting to optometric practices across Canada. Optom Vis Sci. 1997;74:624–631.

3. Clinical Trial #AG9689-001. Data on File, Allergan, Inc.

4. Multi-sponsor surveys, Inc. Gallup study of dry eye sufferers. Princeton, NJ, August 2004.

5. Market Scope. Report on the Global Dry Eye Market. St. Louis, Mo: Market Scope, July 2004.

6. Moss SE, Klein R, Klein BEK. Prevalence of and risk factors for dry eye syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:1264–1268.

7. Schaumberg D, Sullivan D, Buring J, Dana R. Prevalence of dry eye syndrome among U.S. women. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;136:318–326.

8. American Academy of Ophthalmology Cornea/External Disease Panel. Dry Eye Syndrome Preferred Practice Pattern. American Academy of Ophthalmology, San Francisco, California, 2003.

9. Wilson SE. Inflammation: a unifying theory for the origin of dry eye syndrome. Managed Care. 2003;12(12 Suppl):14–19.

10. Smith RE. The tear film complex: pathogenesis and emerging therapies for dry eyes. Cornea. 2005;24(1):1–7.

11. Sullivan DA, Krenzer KL, Sullivan BD, Tolls DB, Toda I, d MR Dana. Does androgen insufficiency cause lacrimal gland inflammation and aqueous tear deficiency? Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:1261–1265.

12. Pflugfelder SP, Beuerman RW, Stern ME. Dry Eye and Ocular Surface Disorders. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker; 2004.

13. Baudouin C. The pathology of dry eye. Surv Ophthalmol. 2001;45 Suppl 2:S211-S220.

14. Stern ME, Beuerman RW, Fox RI, et al. The pathology of dry eye: The interaction between the ocular surface and lacrimal glands. Cornea. 1998;17:584–589.

15. Behrens A, Doyle JJ, Stern L, Chuck RS, McDonnell PJ, and the Dysfunctional Tear Syndrome Study Group. Dysfunctional tear syndrome: a delphi approach to treatment recommendations. Cornea. 2006;25:900–907.

16. Foulks GN. The evolving treatment of dry eye. Ophthalmol Clin N Am. 2003; 16:29–35.

17. Yancey PH. 2001. Water stress, osmolytes, and proteins. Amer. Zool. 41:699–709.

18. Perry HD, Donnenfeld ED. Medications for dry eye syndrome: a drug-therapy review. Managed Care. 2003;12 (12 Suppl):26–32.

|