Endophthalmitis Prophylaxis for Cataract Surgery

A perioperative approach may be warranted, but which antibiotics are effective and safe?

BY FRANCIS S. MAH, M.D.

Endophthalmitis is one of the most feared complications of cataract surgery. Because of its potentially devastating consequences, a number of strategies have been employed for its prophylaxis. These include application of an antiseptic such as povidone-iodine to the lids, lashes and conjunctiva during preparation of the patient for surgery and the topical application of antibiotics to the eye preoperatively and postoperatively.

Recently there has been some controversy surrounding another route of antibiotic application for prophylaxis of endophthalmitis: intracameral injection. A study of endophthalmitis prophylaxis undertaken by the European Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgeons1 found that administration of intracameral cefuroxime at the time of surgery significantly reduced the risk of endophthalmitis developing after cataract surgery.

While some, including this author,2 have critiqued certain aspects of the ESCRS study, the fact remains that it is by far the largest prospective study undertaken to date of the prophylaxis of cataract surgery, and valuable lessons can be drawn from its results.

This article reviews strategies for prevention of endophthalmitis after cataract surgery and provides some recommendations for clinical practice.

Rationale for Prophylaxis

The Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study found that the organisms most often responsible for endophthalmitis were gram-positive, coagulase-negative organisms.3 In that study, 70% of confirmed isolates were gram-positive, coagulase-negative organisms, primarily Staphylococcus epidermidis. Another 24% were other gram-positive organisms, and 6% were gram-negative organisms. The study authors found at the time — in the mid-1990s — that vancomycin was active against all gram-positive isolates tested, and amikacin and ceftazidime had equivalent activity against gram-negative isolates.

Speaker and colleagues,4 using a variety of molecular epidemiologic techniques, showed that the genetic identity of 82% of vitreous isolates in patients who developed postoperative endophthalmitis were indistinguishable from isolates taken from the same patient’s eyelid, conjunctiva or nose.

These findings indicate that organisms associated with postoperative endophthalmitis are usually genetically identical to the patient’s own flora and that the lids, lashes or lacrimal system are the likely source of these organisms.

Another study by Speaker and coworker5 found that the use of povidone-iodine reduced the risk of endophthalmitis by 75% to 80%. Because of this landmark study, preoperative topical application of the povidone-iodine has been widely adopted as a way of minimizing the risk of contamination from the ocular flora.

Choosing a Topical Agent

Another widely practiced approach to endophthalmitis prophylaxis is the use of perioperative topical antibiotics. Although no clinical trial has confirmed this method as effective for prophylaxis, many other studies supply surrogate evidence that antibiotics do provide protection. So if we agree that antibiotics around surgery can prevent endophthalmitis, how do we know which antibiotic to choose for this purpose? It can be helpful to evaluate antibiotic concentrations over time.

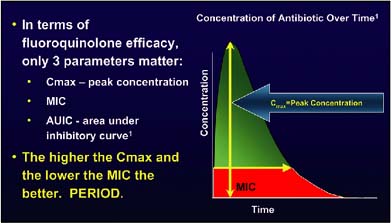

As illustrated in Figure 1, the relationship between the concentration of an antibiotic over time and its effectiveness can be evaluated in vitro models using three parameters: the ratio of the maximum concentration of drug (Cmax) to the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for a given organism (Cmax:MIC ratio); the area under the inhibitory curve (AUIC); and the time above the MIC.6

Figure 1. Explanation of the relationship between the concentration of an antibiotic over time and its effectiveness.

Some antibiotics, such as the fluoroquinolones, have a concentration-dependent effect and therefore require a high concentration over a period of time. Other agents, such as vancomycin, have time-dependent effects.

This means that vancomycin must stay above the MIC for 8 to 12 hours in order to be effective, while fluoroquinolones work in much less time — 1 to 2 hours. With fluoroquinolones, the more antibiotic, the better they work.

According to work by Pickerill and colleagues,7 a Cmax:MIC ratio of 10:1 and an AUIC of 125 or more is predictive of a clinical cure with fluoroquinolones.

Intracameral Approach

As noted above, recent research has stirred controversy about another route of antibiotic administration for prophylaxis in cataract surgery — intracameral injection.

The ESCRS multicenter study of endophthalmitis prophylaxis in cataract surgery1 was a major undertaking with a commendable concept. The study entailed the collaboration of 24 sites in nine countries across Europe.

The prospective, partially masked, placebo-controlled study included four groups: group (A) received no intraoperative antibiotic; group (B) received intracameral cefuroxime only; group (C) received perioperative topical 0.5% levofloxacin only; and group (D) received both intracameral cefuroxime and topical levofloxacin. It is critical to note that in this study it was felt the standard of care included patients in all groups being prepped with povidone-iodine 5% and all received postoperative topical levofloxacin 0.5%.

In the two groups in which intracameral cefuroxime was administered, the rate of endophthalmitis was 5 in 6,836 cases (0.073%), while in the two groups that did not receive cefuroxime the rate was 23 in 6,862 cases (0.33%). The authors noted that the rate in the groups that did not receive cefuroxime was almost five times as high (odds ratio 4.59; 95% confidence interval, 1.74–12.08; P=.002) as that in the groups receiving cefuroxime.

Recommendations for Perioperative Prophylaxis |

Based on what is known to date, some recommendations can be made for perioperative prophylaxis of endophthalmitis after cataract surgery. Periocular conditions such as blepharitis should be treated before surgery. Meticulous lid draping is essential. Povidone-iodine 5% solution should be applied topically to the lids, lashes and conjunctiva with at least 3 minutes contact time preoperatively. A topical fourth-generation fluoroquinolone should be administered preoperatively. High-risk individuals may warrant systemic administration of a fluoroquinolone or a subconjunctival injection of antibiotic. Postoperatively, high-dose topical antibiotics should be prescribed at least four times a day until the epithelium is healed, with no tapering. Regarding intracameral administration of antibiotics, the ESCRS endophthalmitis study may herald a significant shift in the paradigm for cataract surgery. However, more research is needed before we begin using intracameral antibiotics in the 2.5 million cataract surgeries performed each year in the United States. We do not yet know what the optimal drug for this indication will be; one would assume that a broader-spectrum antibiotic such as a newer fluoroquinolone would be better, but more evidence is required. Continued research is needed to find the answers for several variables:

The long-term effects of any of these types and methods of administration must also be assessed. Finally, and most importantly, for the sake of safety, whatever protocol that is ultimately chosen, it must be a simple administration for all in the OR suite so no errors of dilution, mislabeling or solutions can be made. |

Choice of Antibiotics

One concern that has been raised about the ESCRS study is that the overall rate of endophthalmitis is high compared to other recent reports.8 The rate of endophthalmitis in all patients was 28 of 13,698 (0.2%). In those receiving no cefuroxime and no levofloxacin during surgery it was 0.38%.

Several studies suggest that the drugs chosen for the study, cefuroxime and levofloxacin, may not have been the best choices.

The fourth-generation ophthalmic fluoroquinolones, gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin, have been shown to have benefits in comparison to the fluoroquinolone that was used in the study, levofloxacin. The two newer agents have improved spectrums of coverage; they are more potent with lower MICs; and they have delayed antibiotic resistance and better tissue penetration in comparison with levofloxacin.9

Our group at the Charles T. Campbell laboratory at the University of Pittsburgh10 found that fewer bacterial endophthalmitis isolates were resistant to the newest generation of fluoroquinolones. Isolates that were resistant to ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin (second- and third-generation fluoroquinolones) were also resistant to levofloxacin (a third-generation fluoroquinolone), but not to gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin (fourth-generation fluoroquinolones) (Figure 2).

Regarding the intracameral agent, cefuroxime may not have been the best choice either. Cefuroxime provides only average coverage of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. There is a high rate of resistance to the drug, with no coverage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. And it is time dependent, with a kill time of 8 to 12 hours.11

Figure 2. Isolates that were resistant to ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin were also resistant to levofloxacin, but not to gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin.

Other antibiotics that have been used for intracameral prophylaxis have also shown limited efficacy against the organisms commonly responsible for endophthalmitis. Gritz and colleagues12 found that incubation of S epidermidis, S aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates with vancomycin or gentamycin, arguably superior antibiotics to cefuroxime, at bactericidal levels for 2 hours was insufficient to inhibit growth of the organisms.

In a review of endophthalmitis prevention strategies in 2004, Olson13 reported that 5.7% to 43% of uncomplicated phacoemulsification cases can yield positive anterior chamber cultures. Another review, by Gordon,14 found contradictory results in studies regarding whether anterior chamber isolates were reduced by vancomycin prophylaxis. And endophthalmitis has been reported despite use of intracameral vancomycin infusion.15

Fourth-generation Fluoroquinolones

Could a fourth-generation fluoroquinolone provide a better alternative for intracameral prophylaxis in cataract surgery? Experimental and clinical evidence of the safety of moxifloxacin and gatifloxacin for intracameral use is growing.

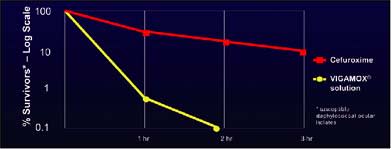

In vitro studies suggest moxifloxacin may have greater efficacy than cefuroxime against the organisms that cause endophthalmitis. In a kinetics-of-kill study that I participated in that was presented last year at the 2006 American Academy of Ophthalmology, in susceptible staphylococcal ocular isolates, moxifloxacin 50 µm/mL (a 1:100 dilution of the commercial ophthalmic preparation) killed more than three logs in 2 hours, while cefuroxime 100 µg/mL or 1,000 µg/mL (a 1:10 or 1:100 dilution) killed less than 1 log in 3 hours (Figure 3).2

In humans, Arshinoff has reported that an intracameral dosage of 100–500 mcg/mL of moxifloxacin has been safe in more than 1,000 surgical cases.2

Espiratu and colleagues16 last year reported on a prospective clinical evaluation of the safety of intracameral moxifloxacin in patients undergoing cataract surgery. Postoperative visual rehabilitation, anterior chamber cell and flare, and endothelial cell density were the principal outcome measures.

The study included 65 eyes of 65 patients (mean age 69.5 years). Intracameral injection of 0.1 mL moxifloxacin 0.5% solution containing 500 µg of the drug was performed with a cannula at the end of cataract surgery.

At postoperative week 4, all eyes achieved BCVA of 20/30 or better, and 86% had a BCVA of 20/20 or better. The mean preoperative endothelial cell count of 2,492 cells/mm2 was not statistically significantly different from the mean postoperative cell count of 2,422 cells/mm2 (95% CI; P=.737). Anterior chamber cell and flare were seen only on day 1 postop.

The study authors concluded that intracameral moxifloxacin 0.5% appears to be non-toxic regarding visual rehabilitation, anterior chamber cell and flare, and endothelial cell density. OM

Figure 3. In susceptible staphylococcal ocular isolates, moxifloxacin 50 µm/mL killed more than three logs in 2 hours, while cefuroxime 100 µg/mL or 1,000 µg/ killed less than 1 log in 3 hours.

References

1. Barry P, Seal DV, Gettinby G, Lees F, Peterson M, Revie CW; ESCRS Endophthalmitis Study Group. ESCRS study of prophylaxis of postoperative endophthalmitis after cataract surgery: preliminary report of principal results from a European multicenter study. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006;32:407–410.

2. O’Brien TP, Arshinoff SA, Mah FM. Perspectives on cefuroxime and the recent ESCRS postoperative endophthalmitis (POE) study. Presented at: Ocular Microbiology and Immunology Group meeting, Las Vegas, November 10, 2006.

3. Han DP, Wisniewski SR, Wilson LA, et al. Spectrum and susceptibilities of microbiologic isolates in the Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;122:1–17.

4. Speaker MG, Milch FA, Shah MK, et al. Role of external bacterial flora in the pathogenesis of acute postoperative endophthalmitis. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:639–649.

5. Speaker MG, Menikoff JA. Prophylaxis of endophthalmitis with topical povidone-iodine. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1769–1775.

6. Zinner SH, Firsov AA. In vitro dynamic model for determining the comparative pharmacology of fluoroquinolones. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 1999;56:S12-S15.

7. Pickerill KE, Paladino JA, Schentag JJ. Comparison of the fluoroquinolones based on pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters. Pharmacotherapy. 2000;20:417–428.

8. Aaberg TM Jr, Flynn HW Jr, Schiffman J, Newton J. Nosocomial acute-onset postoperative endophthalmitis survey: a 10-year review of incidence and outcomes. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:1004–1010.

9. Mah FS. Fourth-generation fluoroquinolones: new topical agents in the war on ocular bacterial infections. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2004;15:316–320.

10. Mather R, Karenchak LM, Romanowski EG, et al. Fourth generation fluoroquinolones: new weapons in the arsenal of ophthalmic antibiotics. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133:463–466.

11. Mah FS. New antibiotics for bacterial infections. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 2003;(16):11–27.

12. Gritz DC, Cevallos AV, Smolin G, Whitcher JP Jr. Antibiotic supplementation of intraocular irrigating solutions. An in vitro model of antibacterial action. Ophthalmology. 1996;103:1204–1208; discussion 1208–9.

13. Olson RJ. Reducing the risk of postoperative endophthalmitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2004;49:S55-S61.

14. Gordon YJ. Vancomycin prophylaxis and emerging resistance: are ophthalmologists the villains? The heroes? Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;131:371–376.

15. Townsend-Pico WA, Meyers SM, Langston RH, Costin JA. Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus endophthalmitis after cataract surgery with intraocular vancomycin. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;121:318–319.

16. Espiratu SG, et al. Evaluation of the safety of prophylactic intracameral Vigamox solution in cataract surgery patients. Poster presented at: 21st Congress of the Asia Pacific Association of Ophthalmology. June 10–11, 2006, Singapore.

| Francis S. Mah, M.D., is assistant professor of ophthalmology at the University of Pittsburgh, and co-medical director of the Charles T. Campbell Ophthalmic Microbiology Laboratory. Dr. Mah is a consultant for and has received research support from Alcon and Allergan. He can be e-mailed at mahfs@upmd.edu. |

|