glucose levels

Are Non-Fasting Glucose Levels Valuable?

Maybe,

but be careful fitting them into the diagnostic puzzle.

BY PAUL S. KOCH, M.D., AND HOWARD

AMIEL, M.D.

Authors' note: Be aware from the start that this article concerns random, non-fasting blood glucose levels in a non-NPO setting. Do not confuse the values presented with fasting blood glucose levels.

At least once a week my nurse slides up to me and whispers, "Your next patient has a blood sugar of 325. Do you want to cancel the case?"

What would you do? Would you make that decision based solely and exclusively on one number in the absence of any other data? Would you like to know the circumstances under which the test was performed? This article will discuss why non-fasting blood glucose levels in a non-NPO setting can be problematic.

Wheaties vs. Donuts

One criterion for the diagnosis of diabetes is the patient having an abnormal glucose tolerance test. In this test the patient is given a glucose load and the blood glucose is checked periodically for several hours. If the blood glucose reaches 200 mg/dL or greater at the 2-hour measurement the patient is confirmed to have diabetes. Naturally, if it is the policy of an ambulatory surgery center (ASC) that patients can eat or drink prior to surgery, then we should expect that patients with diabetes will have elevated blood glucose levels when they arrive, varying widely depending on when and what they ate.

Like many other ASCs we do not have a fasting restriction prior to cataract surgery. We think starving patients prior to a short operation under local anesthesia is unnecessary and so we let them eat or drink right up to the time they are admitted. That means the preoperative glucose levels we get are random and non-fasting, and they are often measured within a few hours of breakfast.

When we check a patient's blood glucose level, we make the assumption that the measurement at that moment in time is a reflection of diabetes control or a reflection of the patient's healing capacity. If, however, the test is taken while the body is in the midst of a glucose challenge, does the test have any validity other than affirming that the patient has diabetes?

|

|

|

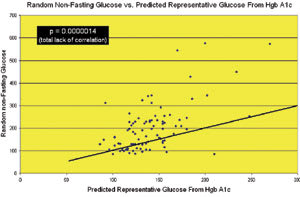

The graph in this figure shows a statistically significant lack of correlation between random non-fasting glucose levels vs.predicted representative glucose from HgbA1c. |

Assessing the Value of Information

We next come to this consideration: Do random blood glucose levels in a non-fasting ASC environment reflect adequacy of diabetes control and, as a corollary, do random blood glucose levels have any predictive value as to whether surgery should proceed or not?

Glucose in the bloodstream binds to hemoglobin and remains attached for the life of the red blood cell, which is about 3 months. During times of high glucose levels, more glucose attaches to the hemoglobin, and during times of low glucose, less glucose attaches to the hemoglobin. Therefore, a measurement of the amount of glucose attached to hemoglobin gives an estimate of the average level of glucose control during the past 3 months. The test measuring glycosylated hemoglobin is usually referred to as the hemoglobin A1c level, or HgbA1c.

While a random blood glucose level tells us nothing about a patient's glucose control, the A1c level does tell us how the patient's average control has been for the past quarter. It is expressed in percentage of glucose attached to the hemoglobin. There are several accepted formulae for converting A1c levels to average blood glucose. (Diabetes Care provides such a table.1) The Joslin Diabetes Center uses the formula:

Average glucose = (A1c x 20) + 10

An A1c level of 7% (corresponding to an average round-the-clock blood glucose level of about 150) is usually accepted as the upper limit of controlled diabetes; a level above that is considered uncontrolled.

We measured both a random blood glucose and also an HgbA1c on 92 diabetic patients coming in for cataract surgery at our ASC to see if a random sugar is in any way a reflection of how well that patient's diabetes is controlled. We converted the A1c levels to average glucose levels using the Joslin formula described above. This allowed us to compare the patient's random blood glucose level on admission with the patient's average blood glucose level for the previous 90 days.

The results were all over the place. In almost equal numbers, we saw all four of the possible patterns:

1. Low A1c, low glucose. These patients maintain good control and did not have a significant glucose load prior to coming in for surgery.

2. Low A1c, high glucose. These patients maintain good control but had a significant glucose load prior to coming in for surgery.

3. High A1c, low glucose. These patients do not maintain good control and did not have a significant glucose load prior to coming in for surgery.

4. High A1c, high glucose. These patients do not maintain good control and also had a significant glucose load prior to coming in for surgery.

There was no correlation between random blood glucose levels in a non-NPO setting and the A1c level, indicating that checking random blood glucose tells us nothing about the level of diabetes control in that patient (Figure). If it tells us nothing, then why do the test in the first place?

The lack of correlation between the two groups reflects the realities of a random blood glucose measurement and that it can be elevated based on whatever the patient had for breakfast regardless of the fasting glucose level. This excludes, of course, other reasons for elevated glucose levels, such as stress or the possibility that the patient's diabetes really might be out of control.

Long-term Glucose Control More Important

If you want to assess a patient's control of diabetes, the best test is the A1c level, not the random blood glucose, because the A1c reflects a multifactorial cascade in diabetes management — diet control, medication regulation and medication compliance, averaged over 3 months. Evaluating the patient with diabetes is far more complicated than making assumptions based on a single random test.

Here is an extreme, but completely true example: One of our patients arrived for surgery with a random blood glucose of 574 and an A1c of 13%. You'd cancel that patient, right?

Wouldn't you like to know the rest of her story? She had a breakfast of eggs, pancakes, bacon and coffee with three sugars prior to coming in for surgery. Her elevated A1c (indicating an average blood glucose of 270) reflected her lifestyle of attending birthday parties for her many grandchildren several times a month and eating cake at each, treating herself to a "reward" snack each evening and using her insulin when she felt like it — less frequently now that she had trouble seeing. She had been a diabetic for more than 10 years and regularly saw an excellent diabetic specialist who, after years of coaxing, cajoling, threatening and begging, finally accepted her lifestyle as unchangeable. They finally reached the point where she would call his office and let him know whenever her glucose levels (which she measured every few days) exceeded 700.

We did not believe her and called her doctor who confirmed everything. "She's 574 after that breakfast?" he laughed. "She must have been about 250 on her fasting. That's pretty good for her. You're lucky you're getting her on a good day!"

This brings us to this question: Can it be that using random glucose levels to decide whether to proceed with surgery is simply "fluffing the chart," making it appear that we have a rational system for evaluating patients with diabetes prior to cataract surgery when, in fact, the random glucose test is irrelevant?

Quite possibly, yes.

We do not believe that a short-term fix, sending the patient home for a few days and rechecking the glucose, perhaps after fasting, and then performing the operation changes the overall picture of diabetes control and ophthalmic morbidity. The only way to effect a change would be for the patient to undergo a wholesale reassessment of his or her lifestyle and make a firm commitment to control — including diet, medication and compliance.

Glucose a Small Part of theDiagnostic Puzzle

So what do we do? We evaluate out patients with diabetes not with just a random test, but with a personal assessment. We still measure the random blood glucose, but we use it as just one screening criterion prior to performing surgery. We do not make a decision based exclusively on that test. We also do a physical assessment of the patient to decide whether the patient is healthy enough to undergo the operation. We communicate with the patient's endocrinologist or personal physician, when needed, and coordinate our needs and assessment with their input and insight.

Patients with diabetes remain some of our most challenging patients, and we feel the best way to evaluate them for surgery is by personal assessment. If laboratory tests are to be used, the A1c is the best measure of diabetes control. The fasting blood glucose is also a useful test. However, a random non-fasting blood glucose test in a non-NPO setting doesn't really help us. In the absence of any other assessment, it only confirms that the patient really does have diabetes, but we knew that anyway.

Paul S. Koch, M.D., is the chief medical editor of Ophthalmology Management and isco-founder and medical director of Koch Eye Associates in Warwick, R.I.

Howard Amiel, M.D., is currently a fellow at the Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital in Melbourne, Australia.

Reference

1. Rohlfing CL, Wiedmeyer H-M, Little RR, England JD, Tennill A, Goldstein DE. Defining the relationship between plasma glucose and HbA1c: analysis of glucose profiles and HbA1c in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:275-278.