Targeting the Problem

Coordinated diagnostics will guide successful treatment of ocular surface disease. Here are some helpful tips.

|

|

|

|

"You can become fairly comfortable looking at a meniscus, just as you can evaluating the density of a cataract." -- John Sheppard, M.D. |

|

Accurately diagnosing dry eye requires analyzing symptoms and signs using a variety of available technologies. Although strides have been made in the development of new diagnostic tests -- wavefront technology will prove helpful, for example -- success lies in understanding the nature of symptoms and how to effectively use existing tests and techniques. Here's a quick review of how these leading experts approach the process.

Make sense of symptoms

A reliable link between signs and symptoms of ocular surface disease still has not been esablished, says Michael Lemp, M.D. Consider these confounding factors:

- Signs such as staining may not manifest until late stages of the disease. "Ocular surface sensory receptors are very sensitive to changes in tear film and can set off symptoms of distress at a much earlier stage, when signs are not present," Dr. Lemp says. "These patients still have an intact sensation. They have an ability to blink more frequently. They're symptomatic but they're protecting the surface from breakdown through the compensatory mechanisms of increased blinking."

- Tests such as Schirmer can be variable, depending on how they're performed. "Test results may not become consistent until the patient's disease becomes severe," Dr. Lemp says. "Then the tests become very important. We don't have good early diagnostic signs for early disease, but the symptoms are very important."

- Some patients with severe ocular surface disease will have few symptoms. Even with severe staining, patients may feel that their eyes are fine, usually because of a down-regulation of the sensory receptors on the surface of the eye, Dr. Lemp says.

- Symptoms are very subjective. "One person's foreign body sensation is another person's itchiness," Dr. Lemp says. "Even if a patient says 'It doesn't bother me that much.' You have to listen to his symptoms."

Ocular fatigue, associated with an increased blink rate, may be the most reliable symptom of ocular surface disease, says Dr. Lemp. The average blink rate is 13 blinks per minute, but this can decrease when people are looking at computers or reading.

"Patients often can't articulate this symptom very well. They're simply uncomfortable with their eyes. And that's clearly related to a rapid breakup in tear film stability between blinks," Dr. Lemp says. "Even though the patient may not have signs, you should go ahead and treat. Many of these patients don't have conditions that will get worse, but they still need treatment."

|

|

|

Lissamine green staining is a useful test for patients who seem to have inconsistent symptom-to-sign ratios. |

Test for signs

A comprehensive patient history will uncover suspicion of ocular surface disease. Then you can begin a diagnostic course that may include:

- Penlight reflex on cornea. Perform this simple test while taking a patient's history so as not to induce changes in his blink rate. "A breakup of the reflex on the cornea alerts me right away that I should be concerned about tear breakup and tear instability or ocular surface disease of some type," says Gary Foulks, M.D., professor of ophthalmology at the University of Louisville in Kentucky.

- Fluorescein staining. Some ophthalmologists use drops; others use a strip to avoid the corrupting effects of drop additives, such as benzalkonium chloride and benoxinate.

"Unless you use a micropipette with the drops, which can be impractical in clinical practice, you'll likely get inconsistent results, determined by the amount of stain that enters the eye and how long it takes before breakdown begins," Dr. Lemp says. "Repeated use of the stain at 5 microliters each time will start to show fairly reproducible results. Breakup time of less than 10 seconds should be considered abnormal, reflecting tear film dysfunction.

|

|

|

|

"A careful patient history is really important because what medications a patient is taking can contribute to some of their symptoms, or maybe even exacerbate them." -- Richard Fiscella, R.Ph. |

|

"The reliability of this test as an indicator of tear film dysfunction will decrease if you first do lissamine green staining. It's going to break up over that stained area very rapidly."

- Lissamine green staining. "This is a very useful test for patients who seem to have inconsistent symptom-to-sign ratios," says John Sheppard, M.D. This test and the Schirmer tear test are the first ones he uses to keep it simple. "Obviously if someone has corneal punctate keratopathy, I'm finished," he says. "I know they have ocular surface disease and it's time to treat. But many patients may have only conjunctival epithelial changes, which are more readily apparent with lissamine green."

- Tear meniscus height. "Doctors rarely talk about this indicator, but you can become fairly comfortable looking at a meniscus, just as you can evaluating the density of a cataract," Dr. Sheppard says. "This is a subjective test, but you can develop a great feel for it."

Patients with severe dry eye disease will have no tear meniscus at the junction of the lower lid and the inferior bulbar conjunctiva. "This can be a sign of both aqueous deficiency and evaporative dry eye," Dr Sheppard says.

- Schirmer test. Some ophthalmologists, including Dr. Sheppard, find the Schirmer test useful to manage patients, especially those with extremely dry eyes. Before doing the test, he has a technician administer a drop of proparacaine or tetracaine anesthetic in each eye.

|

|

|

Some ophthalmologists find a Schirmer test useful to manage patients, especially those with extremely dry eye. |

A result of less than 5 mm over 5 minutes prompts him to initiate immediate punctal occlusion. "Anyone under 5 mm has a significant aqueous deficiency," he says. "We are very aggressive with those patients in terms of punctal occlusion."

Edward Manche, M.D., uses the Schirmer test without anesthesia to rule out refractive surgery candidates and recognize potential Sjögren patients. "Even with noxious stimuli, Sjögren patients will not produce tears," he says.

Dr. Sheppard agrees. "A Schirmer test without anesthesia is even more convincing when dry," he says. "This indicates once again the need for aggressive therapy, including punctal occlusion."

Ella G. Faktorovich, M.D., uses the Schirmer test in conjunction with the tear breakup time test to differentiate between evaporative and aqueous tear deficient dry eye.

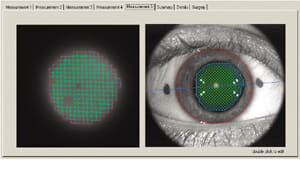

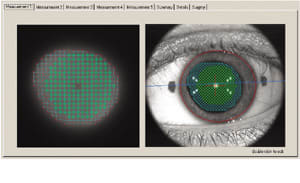

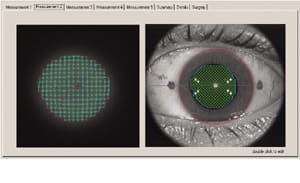

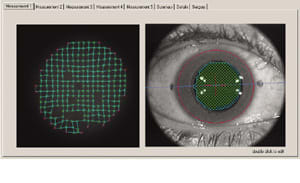

- Wavefront technology. Although not yet widely used as a diagnostic tool for ocular surface disease, wavefront technology may provide additional important information to clinicians. Dr. Faktorovich uses the aberrometer to objectively evaluate a patient's response to dry eye therapy. First, she dilates the pupil to ensure the capture of as much of the corneal surface as possible. "Three things -- absent data points, uneven grid and abnormal aberrations -- could perhaps be useful in following patients and documenting the objective response to dry eye therapy," she says.

Increase vigilance

Diagnosing dry eye appropriately often is a matter of increasing your awareness and using the right combination of techniques. "If we coordinate our efforts in all these areas, we can do a high-quality diagnostic job," says Richard Lindstrom, M.D.

|

Charting Your Diagnosis |

| Physicians often chart their patients using a simple menu to diagnose ocular surface diseases. "We grade the punctate keratopathy right and left, the tear meniscus right and left, the degree of blepharitis and the meibomian gland dysfunction," says John Sheppard, M.D., explaining how he charts the treatment of ocular surface disease. "In 99.9% of patients, we'll list one of three ocular surface diseases: Blepharitis, allergy or dry eye, and we proceed from there," he says. "These diseases may overlap. For instance, a patient who itches may have both dry eye and allergy, depending upon the degree of papillary conjunctivitis we see in the superior tarsus, and we treat accordingly. We treat the worst symptoms first, unless we see signs that are more alarming." Gary Foulks, M.D., ranks the diagnoses according to their significance in the patient's dry eye presentation and his findings. "I rank them by the component that's contributing the most because that's where I'll focus my therapy," he says. "If I think their meibomian gland disease is the main problem, I'll pull out all stops to treat the meibomian gland disease while also trying to stabilize the tear film." Ella G. Faktorovich, M.D., writes "evaporative dry eye," "aqueous deficient dry eye" or "both," and then comes up with a differential diagnosis for each of them. Another fact to consider when charting is that no ICD-9 code exists for ocular surface disease, according to Dr. Foulks. "To coordinate your chart with the billing sheet, you'll need to let your coding and reimbursement coordinators know they'll need to select a code for something other than ocular surface disease," he says. |

|

|

|

|

| Absent data points (top) and uneven grids (bottom) are useful in following patients and looking at objective response to dry eye therapy | |

|

Thorough Patient History |

| To

uncover dry eye disease, be sure to include the

following questions when taking a patient's history: 1. What symptoms are you currently experiencing? 2. Have you experienced these symptoms before? For how long? 3. When is the last time you saw an eye doctor? 4. Are you taking any prescription medicines for dry eye disease? 5. What other prescription medicines are you currently taking? 6. Are you taking an over-the-counter decongestant or antihistamine? 7. Are you taking any other over-the-counter medications? "By the time many patients seek medical attention, they have medicamentosus from products they've been using. They have no idea what's wrong with their eyes; they're just trying to get some relief." -- John Sheppard, M.D. |