Moving the Macula

A little more than a decade ago, macular

translocation surgery was conceived by a

vitreoretinal pioneer. Today, his protégé is working to improve the procedure for wet AMD patients.

BY ROCHELLE NATALONI

Macular translocation surgery (MTS) is based on a simple concept: lifting the macula away from underlying abnormal blood vessels and moving it to a new, healthier location to restore central vision in people with end-stage AMD. The best candidates are those who have central vision loss in one eye and have experienced recent vision loss-- specifically within the previous 6 months -- in their second eye.

The procedure, which has been around in various permutations for about a decade, has made recent strides as a result of research at the Duke Center for Macular Degeneration at the Duke University Eye Center. Cynthia A. Toth, M.D., who is the only surgeon in the United States performing the procedure in large numbers of patients, compares it, for lack of a better analogy, to an internal transplant. "We're simply shifting the macula over to a healthier spot," she said. "What's amazing is the finding that the macula itself can actually function over tissue that is not ordinarily beneath the macula." Dr. Toth is associate professor of ophthalmology at Duke. "That's been a phenomenal finding for us because it helps us understand a lot about the recovery of the retina, which will come in handy in the future if we're able to transplant tissue in," she added.

MTS was the brainchild of vitreoretinal surgery pioneer, Robert Machemer, M.D. Early reports indicated that MTS was effective in restoring vision in as many patients as not, and that complications were frequent. But one of Dr. Machemer's earliest patients recovered vision to 20/50. That result, says Dr. Toth, was enough to keep Dr. Machemer pushing onward.

|

|

|

-- Cynthia A. Toth, M.D. |

|

Dr. Machemer retired soon after introducing MTS and passed the baton to Dr. Toth, who's done more than 200 of these surgeries since 1996. Her version of the procedure is called MTS360, and goes like this: A three-port pars plana vitrectomy is performed, the retina is detached, and a peripheral 360-degree retinectomy is performed. The CNV complex is removed, the retina is rotated superiorly and then reattached using perfluorocarbon. Endolaser is performed to the edges of the retinectomy, and a silicone oil perfluorocarbon exchange is performed. Patients are instructed to maintain strict positioning following surgery for 10 days. Eight weeks post-op, they return for extraocular muscle surgery to repair tilted vision that results from the retina repositioning. Sharon Freedman, M.D., developed the muscle surgery, and it is performed by her or her associates. At that point, the silicone oil is removed.

According to Dr. Toth, other U.S. retina specialists are performing the MTS360 procedure, but, as far as she knows, not in great volume. No medical center besides Duke has come out and announced the availability of the sought-after surgery. Dr. Toth has had patients come to North Carolina for macular translocation surgery from as far away as Texas, as well as from up and down the East Coast. She says she discourages people from traveling great distances for the procedure because of concerns about appropriate follow-up care, and because it requires a return trip for the extraocular muscle surgery.

|

|

|

|

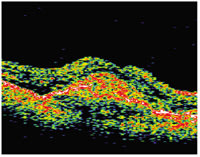

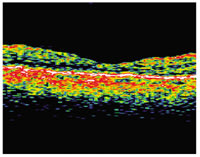

| This patient with

predominantly classic choroidal neovascularization of approximately 6 Macular Photocoagulation Study disc areas (images to the far left) had distance vision of 20/64, near vision of 20/100 and a reading speed of 109 words per minute. At 1 year after an MTS360 procedure (images to the right), distance vision was 20/40, near vision was 20/20 and reading speed was 150 words per minute. At 2 years post-op, distance vision was 20/40, near vision was 20/25 and reading was 171 words per minute. |

|

Today's Challenge: Predicting Who Will Benefit

Dr. Toth learned how to perform macular translocation surgery under the tutelage of Dr. Machemer and then collaborated with and learned about muscle surgery techniques from German surgeon Claus Eckardt, M.D., who was second only to Dr. Machemer in publishing outcomes on a series of macular translocation patients. Since then she and colleagues at the Duke Center for Macular Degeneration brought the surgery to new heights. "When I first started doing MTS, it was a 6- to-8-hour general anesthesia procedure. Now it's a 2-hour local anesthesia procedure," she said. "We've taken it from a high-risk operation for an elderly person to something that is a reasonable risk," she explained. She and her colleagues have also significantly reduced the rate of retinal detachment. "We had a very high rate of retinal detachment in the beginning of around 40%, and we've been able to reduce that to 10% or less," said Dr. Toth. "I'm proud of what we've accomplished, but we still have a long way to go."

The addition of Dr. Freedman's extraocular muscle surgery overcame the post-op tilted vision that had been a long-standing challenge. Now Dr. Toth has bigger fish to fry. "We do not have a good way of measuring when the retina is or isn't recoverable. We need to devise some sort of diagnostic method to identify patients who will and won't benefit from translocation surgery," she said, "and that's what I'm working on now."

Outcomes have been mixed because of that inability to discern beforehand who will most likely benefit from the procedure, but a 2002 Duke study concluded that macular translocation with 360° peripheral retinectomy and silicone oil tamponade stabilizes and can sometimes improve near and distance visual acuity and reading speed in patients with vision loss from subfoveal neovascular AMD.

The study looked at near and distance visual acuity and reading speeds following MTS360 in 15 patients with large subfoveal CNV lesions. The median lesion size was 9 Macular Photocoagulation Study (MPS) disc areas, out of a range of 4 to 16 disc areas. The median near visual acuity logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) score improved significantly from 0.54 units to 0.40 units, or 20/70 to 20/50, 6 months out, and stabilized at 20/70 one year out. Seven of 13 patients and seven of 12 patients achieved reading speeds of 70 words per minute or greater at the 6-month and 12-month postoperative visits, respectively. "Our patients who can get back to reading are amazing cheerleaders and provide endless inspiration," said Dr. Toth. Median preoperative distance visual acuity of 20/100 was maintained at both the 6-month and 12-month examinations, and no postoperative retinal detachments occurred in this series. (Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:1317-1324.)

A more recent report looked at MTS360 quality of life (QOL) outcomes before and after surgery. "We used the National Eye Institute's VFQ25, and we looked at quality of life of 44 patients before and after surgery," explained Dr. Toth. "We found that the patients' mean quality of life overall improved as far out as a year later, and that the perception of their quality of life was higher in patients in whom we had measured better visual acuity," she said. Most postoperative VFQ25 QOL scores were significantly higher than the preoperative scores, and improved visual function related to greater improvement in vision-specific QOL. "In a way, this validated the findings that we get when we measure visual acuity. We tell people that we may be able to help them, and by asking the patients a very specific set of questions, we were able to find out that we really were helping them," she said.

The most recent reports on MTS360 relate to significant subsets of patients. One looked at distance and near vision, as well as reading speed in 64 patients with the worst form of wet AMD, and the other is a much smaller group of eight patients who have already had ocular photodynamic therapy. The retrospective study of wet AMD patients showed that overall the group had an improvement of 1 line of vision, according to Dr. Toth. "This is notable because of the severe nature of the disease that we are treating, because the lesions that we treat generally are quite large," she said.

The study of patients who had MTS following PDT offered hopeful outcomes. "Until now MT360 had been used in patients with recent central vision loss from AMD in their newly affected second eye, but it hadn't been evaluated in patients who had undergone previous macular treatment. We wondered if the verteporfin therapy might have had an effect on the retina that would make MTS ineffective," Dr. Toth said. The study showed that MTS360 appears to be a viable option for patients who are continuing to lose vision in their better-seeing eye following PDT with verteporfin. "We now have shown that this may be an option for patients who are experiencing continued vision loss despite previous treatments for AMD," she said. "The take-home message to me was we don't have to exclude patients who have already had PDT once or possibly even twice -- which means patients who opt for the non-surgical treatment and aren't helped still have a chance with the surgery."

The majority of the patients who lose vision while undergoing other treatments for macular degeneration usually lose it in the first 6 months of treatment, Toth explained. "So after one or two treatments, if the patient loses vision with that other treatment, rather than continuing on and doing three, four, or five treatments, the patient may wish to contemplate MTS," she said.

Dr. Toth has subsequently performed MTS on additional patients who've had three or more PDT treatments, and although it's only an anecdotal observation, she says she's not optimistic about recovering vision with translocation in those patients. "I think that's due in part to the fact that a period of time has gone by, and the lesions have been there for a long time. Our general rule for translocation has been catching people in the first 6 months," she said.

How MTS Fits In

Dr. Toth doesn't see MTS taking over as first or even second-line AMD treatment any time soon. "It's quite complex because it requires two operations, so it's playing a very small role in America today," she said. "If another therapy can stabilize or maintain vision at a reasonable level say 20/80 and the patient can read with low-vision assistance, then maybe we shouldn't push for complex surgical intervention. But if they have vision loss in one eye and are beginning to lose vision in the other, it's nice that we now have something else that could potentially be tried," she said.

Dr. Toth hopes more surgeons will begin exploring the possibility of providing MTS for the obvious reason that it would then be available to greater numbers of patients, but also because it would increase the speed with which MTS can be refined and improved. "There are limits to my creativity," she said. "If others come along and try this, they are bound to add tweaks and innovations that will help," she said.

The future is bright for this procedure that essentially is still in its infancy. "We've learned how the retina recovers and how to control recovery and how to improve recovery because we're basically taking a very damaged fovea and recovering as much vision as possible, but we still haven't maximized all the pharmacologic therapies that we could use to help regenerate the macula once we put it in a healthier spot," said Dr. Toth. "So we still have a lot to learn."

|

For More Information |

For MTS course and wet lab information, see http://mactrans.dukeeye.org/macTransCourse.asp |