Education Forum Recap

Creating Compatible IOLs

Restoring crisp vision is the ultimate goal of cataract surgery. Make sure you succeed by choosing the best IOL for each patient.

| MODERATOR:

|

|

| PANEL:

|

Robert J. Noecker, M.D., Pittsburgh |

Eric D. Donnenfeld, M.D.: We've made tremendous progress designing IOLs that can slow or prevent the formation of posterior capsule opacification (PCO) and reduce the incidence of dysphotopsias. However, more recent design advances -- one-piece and three-piece IOLs, new silicone and acrylic materials -- have grown out of our desire to improve biocompatibility.

Capsular biocompatibility

Donnenfeld: How has biocompatibility influenced IOL design, particularly with regard to anterior square edges?

Robert J. Noecker, M.D.: In the past, we wanted to place any IOL into the eye as quickly and easily as possible. Since then, we've learned a lot more about how IOLs interact with eye tissues in the longer term.

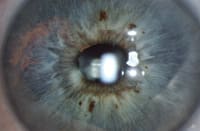

Donnenfeld: We've all seen iris transillumination with pigment dispersion syndrome, usually in young, healthy myopes. Is this similar to what we're seeing after IOL implantation?

Noecker: Yes. Iris chafing and pigment dispersion are relatively unrecognized consequences of suboptimal IOL placement or IOL migration. We've seen cases of pigment displacement in patients who have one-piece, square-edged AcrySof lenses in their sulci, or in patients whose lens migrated from the sulcus to the capsular bag. In our case series of about six patients with large or irregular capsulorhexis, we can see pigment on the IOL corresponding to an area on the pigment-denuded iris. We also can see the displaced pigment inferiorly in the angle where it settled after coming off the iris. Compared with one-piece IOLs, most three-piece IOLs have a posterior haptic angle that keeps the edge of the optic from chafing the iris.

Donnenfeld: So, given a choice, would you use a one-piece or a three-piece IOL in your patients?

Noecker: I think the three-piece design is better for capsular biocompatibility.

Uveal biocompatibility

Donnenfeld: We all do cataract surgery on patients with uveitis. What IOL design features are beneficial for with patients with inflammation?

Thomas W. Samuelson, M.D.: I do a lot of glaucoma and high-risk cataract surgery, so I'm primarily concerned with uveal biocompatibility. I want to use IOLs that resist giant cell deposition and other inflammatory reactions, which means being careful about the materials I use.

Literature from the 1990s uniformly advised against using silicone IOLs in high-risk eyes. I believe this was an appropriate warning for the materials available at that time, which were thicker, had a lower refractive index, and were less chemically pure than current silicones. But when AMO changed from the SLM-1 material to SLM-2 we had fewer problems with uveal biocompatibility. We started seeing the new acrylic materials around this same time, but I was having such great success with the new-generation silicones that I decided to stay with them. I did, however, do a study comparing the materials.

In a prospective, randomized study, high-risk patients received acrylic, new-generation silicone (SLM-2) or first-generation silicone IOLs. The first-generation silicone showed considerable giant cell deposition at rates that were consistent with those reported in the literature. Acrylic lenses showed intermediate giant cell deposition, and of the three materials, the second-generation silicone lenses were least likely to cause inflammation.

Both acrylic and new-generation silicones perform well in high-risk eyes; however, the bulk of the literature suggests that the new-generation silicones are more biocompatible for eyes prone to inflammation and giant cell deposition.

Donnenfeld: Can you comment on one- and three-piece IOL designs for inflammatory patients?

Noecker: ClariFlex is my lens of choice.

However, for a patient with inadequate or concave capsulorhexis, edge design plays a greater role in causing inflammation than lens material, so I'd probably think twice before using a squared anterior edge IOL. Otherwise, I agree that modern silicone IOLs do very well in the eye.

Samuelson: I've used toric one-piece acrylic IOLs for really low-risk, high-astigmatism eyes with good results. But this lens still has some early generation silicone characteristics, so I'm cautious about using silicone one-piece plate lenses unless they're new-generation silicone.

Building harmonious IOLs

Donnenfeld: What have we learned about the importance of IOL design for capsular and uveal biocompatibility?

Noecker: Many of our lens innovations are the result of happenstance. Posterior square edges decrease PCO, and rounded front edges not only cause fewer optical disturbances, but also decrease the incidence of pigment dispersion.

Donnenfeld: Which IOL polymers do you like best, and why?

Samuelson: I prefer silicone. The bulk of evidence suggests that recent-generation silicone is the most biocompatible material for preventing giant cell deposition.

Third in a series sponsored by

The AMO logo is a trademark and AMO and ClariFlex are registered trademarks of Advanced Medical Optics, Inc. AcrySof is a registered trademark of Alcon, Inc.