Bimanual

Microincision Phaco

A guide to help you prepare for the future of cataract removal.

BY DESIREE IFFT, EXECUTIVE EDITOR

The availability of heat-reducing phaco technologies certainly renewed interest in removing cataracts through two stab incisions, a concept that's been around since the 1970s. But that interest has been tempered for most surgeons by the lack of an FDA-approved IOL that could be implanted through an incision as small as 1.2 mm. If you're among those who decided not to bother with the technique until a compatible IOL comes along, you may want to reconsider.

Bimanual microincision phaco has advanced beyond where it was 6 to 12 months ago. During that time, interested surgeons have been fine-tuning the technique, resolving the fluidics issues, and working with instrument companies to design the right tools.

Some believe the technique will become the standard of care in the near future. Others do not, but in this article, they all share their advice for performing it safely and effectively.

"Personally, I don't think that bimanual phaco presently offers any major benefits over coaxial phaco, which remains my preference right now," says David F. Chang, M.D. "However, I am impressed with how far bimanual phaco has progressed during the past year. We can do the whole spectrum of cataract densities safely with this technique."

Currently, Dr. Chang performs bimanual microincision phaco in less than 10% of his cataract cases, mostly in the interest of evaluating and improving the procedure. "Six to 12 months ago, I thought that the procedure would be more difficult for most people to do because the fluidics are less forgiving," he says. "It was definitely a compromise in the past to have to work at a lower vacuum for the sake of safety. But the gap in fluidics between standard coaxial phaco and bimanual microincision phaco is now closing because we have tools that are a big improvement from just a year ago."

Fluidics has been the real challenge. Irrigation inflow is reduced because the coaxial infusion sleeve is eliminated. To handle that reduced inflow and keep the anterior chamber stable, surgeons do one of three things:

- raise the infusion bottle

- decrease the vacuum level/aspiration rate

- use forced infusion with an external mechanism such as a positive-pressure pump.

You can raise the bottle without causing dangerously high IOP, as long as you have aspiration and irrigation both working at the same time, says Randall Olson, M.D. On the AMO Sovereign with WhiteStar he uses vacuum no higher than 350 mmHg and flow no higher than 24 ml/min.

"It turns out that things move faster than you would expect at 22 or 24 ml per minute because in coaxial phaco, a lot of the irrigant just gets sucked right back up the phaco needle doing no effective work," he explains. "I think we lose about a third of our fluid when we're doing coaxial phaco. With microincision phaco, 20 ml per minute of flow feels more like 30, and 24 feels more like 36."

In addition to raising the bottle to maximize inflow, Dr. Olson recommends using tubing with walls as thin as possible, and making appropriately sized incisions (sized to your instruments). (See "Creating Ideal Incisions".) "With thin-walled tubing and appropriately sized wounds, chambers have been absolutely rock-solid," he says.

Some surgeons find that forcing infusion works well, but that can create its own problems, according to I. Howard Fine, M.D. "You can pressurize with air, but air is elastic so you won't get a constant pressure," he says.

Having the right irrigating chopper also makes a difference. Many instrument companies now offer irrigating choppers designed especially for bimanual microincision phaco. One, for example, provides a flow rate as high as 40 ml/min at a bottle height of 30 in. for a 20-gauge system. (Most surgeons who perform bimanual microincision phaco are using 20-gauge instrumentation through 1.2-mm to 1.4-mm incisions.) Another provides as much flow as 82 ml/min.

Some have single ports at the end, which Dr. Olson prefers, instead of an opening on each side. "If you've got two holes, they need to be as large as possible, and maybe oval," he says. "Two 0.3-mm holes just aren't going to cut it; you're going to impede your flow too much. Also, when you've got two holes, your flow is more complex and it's more difficult to use your irrigation as an instrument."

Dr. Fine prefers a front irrigator as well. "It's more useful because as soon as you touch the outer lips of the incision, it inflates the eye," he explains. "A side-port irrigator has to be all the way in before it starts to inflate the eye."

Dr. Chang points out another potential problem with two sideports: "You have to be very careful that you don't pull the chopper back too far so that the irrigating openings come out of the incision and you lose your irrigation flow."

Specialized keratomes and handpieces are now available, as are microincision capsulorhexis forceps. "Because of the development of the new instrumentation, especially bimanual microincision capsulorhexis forceps, we can do subluxed lenses and zonular weaknesses without fluctuations of the chamber during capsulorhexis formation," explains Dr. Fine. "With previously available forceps, there tended to be an egress of visco during rhexis, but now that doesn't happen."

Surgeons also take into account phaco tip selection. Most agree that a flared tip is not a good design for microphaco and are using straight, 30-degree beveled tips. Dr. Fine uses his with the bevel pointed down. Richard Packard, M.D., doesn't perform bimanual microincision phaco routinely, but when he does he uses the 30-degree bevel. "For soft or hard cataracts, the extra curve works like a finger in the eye. You can move tissue around with it," he says.

A final note on tips from Dr. Olson: "I've had some that were too short, so when I pushed up and tried to turn, they went into the cornea. I couldn't get them in."

Safety and Flexibility Among the Benefits

Now that they're working with tools specifically designed for bimanual microincision phaco, Dr. Fine and his partners, Richard Hoffman, M.D., and Mark Packer, M.D., use the technique in more than 95% of their cataract cases, a much higher volume than other surgeons at this point. They consider the procedure to be superior to coaxial phaco now. "It's closer to the ideal procedure, which would be a 100% closed system," says Dr. Fine.

For others, bimanual microincison phaco isn't the procedure of choice right now, but they also cite benefits:

Better followability. "When an irrigation sleeve isn't just pushing fragments away, and there's no place for the material to go except to your phaco needle, it tends to follow better, so you don't have to chase things the way you did before," says Dr. Olson.

Dr. Fine concurs: "It's really an advantage to have all of the fluid coming in from one location and all of the fluid leaving from another. There are never competing currents of fluid, which you can get with coaxial phaco."

Irrigation as a second tool. Because irrigation and the phaco needle are separated, you can use irrigation to drive material to the phaco tip. You can also use it to flip the epinucleus, as Dr. Fine does.

Safety might be enhanced as well. According to Dr. Olson, "A study would have to prove this, but if you use irrigation appropriately and don't use your phaco tip near the capsule, it would seem to me that you would significantly reduce your capsule breakage rate."

He also cites the minor advantage of being able to use irrigation to move the iris away in pseudoexfoliation cases. Others suggest that freed-up irrigation could also lead to less endothelial cell loss because it can be used to push material off the capsule and to clear out the fornix.

Deep, stable chamber through the entire procedure. This is easier to accomplish when you're performing phaco through smaller incisions. Also, viscoelastic doesn't leave the eye easily, so the anterior chamber is more stable during capsulorhexis construction, making the development of an errant rhexis much less likely. For these reasons, bimanual microphaco is Dr. Olson's procedure of choice when he's dealing with a hypermature cataract and a tense capsule.

Furthermore, as Dr. Hoffman, explains, if you use infusion and viscoelastic to keep the eye pressurized during all aspects of the procedure, it may result in a lower incidence of surgically induced posterior vitreous detachment and cystoid macular edema. "The lens-iris complex, and therefore the vitreous, would not be trampolining forward and backward from hypotony and chamber re-establishment, which frequently occurs during coaxial phaco as we remove instruments from the eye," he says. "This would need to be shown with a controlled study, but it makes sense theoretically."

Should this theory, originally proposed by Dr. Fine, pan out, bimanual microincision phaco would also be a much better technique than standard phaco for refractive lens exchange patients, who might be high myopes and thus prone to vitreous detachment and retinal tears.

William Fishkind, M.D., performs bimanual microincision refractive lens exchange with this theory in mind. "I fill the anterior chamber with viscoelastic, of course, for the capsulorhexis and keep the chamber maintained at all times," he says. "Before I remove the phaco tip, I refill the chamber with BSS and visco and implant the IOL. Then, the irrigation/aspiration instruments go in, I perform I/A and remove the visco, and only remove the instruments when the chamber is pressurized."

Ability to switch instruments. You can remove subincisional cortex easily because you can reach 360 degrees of the capsular fornices by switching infusion and aspiration handpieces between the two incisions.

A recent case of Dr. Fine's, a subluxed cataract that was referred to him, illustrates the utility of switching instruments. "I put a capsular tension ring in and was doing bimanual temporally," he reports. "The main area of weakened zonules was the inferior temporal quadrant. My phaco sideport incision was in the superior temporal quadrant, so as vacuum was activated, it was drawing things toward the superior location, pulling on the capsule and its contents, widening the dialysis, even though I had hydrodissected the lens out of the bag. So, I switched my handpieces -- put my phaco needle through the inferior temporal sideport and my irrigation chopper through the superior temporal incision -- and then everything was being pulled toward the dialysis, closing it, putting less stress on it. I'm not a left-handed phaco surgeon, but it worked beautifully."

Extra help in special cases. "Just like bimanual I/A, bimanual phaco can be helpful when you have a problem with the posterior capsule, such as a large zonular defect," Dr. Chang says. "You're working through very tight incisions that give an excellent fluidic seal, so you minimize the chance of drawing vitreous up to the incision along with the exiting fluid current. In addition, separating the irrigation and aspiration ports helps you avoid a fluid misdirection syndrome. In this setting, I also use a lower aspiration flow and vacuum rate to slow things down." Dr. Chang has successfully used bimanual microincision phaco in five cases involving large zonular defects.

He and Dr. Fine describe the technique as suitable for ruptured capsule cases. The tight incisions, separate irrigation, and low flow and vacuum are key here. Dr. Fine was able to finish a recent case in which the posterior capsule was punctured by going down into the bag with the phaco needle to raise the remaining lens pieces into the anterior chamber. "I was able to do that because irrigation is high in the anterior chamber, the bag remains inflated, and I didn't have to drag turbulent irrigation down there with me."

No absolute contraindications. None of the surgeons we interviewed considered any cataract case a contraindication for performing bimanual microincision phaco. But some did mention that they might not use the technique when they're also using an adjunct device, such as a pupil dilator, or when they're doing iris repair or dealing with zonular dialysis, where they might need a larger incision. "They're not even contraindications; you just don't gain much by doing bimanual is some of these cases," Dr. Olson says.

Also, because the technique is relatively new, some surgeons don't use it for certain complicated cataracts. Dr. Chang expresses it this way: "When you're faced with a difficult case, you should use your best procedure, and right now I have much greater experience with coaxial phaco."

Compatible with any phaco style. At first, Dr. Fishkind only used a chop technique for microincision cases. "But now," he says, "I do it with divide and conquer, and I've done it with stop and chop, and they all work well. I just did a very hard nucleus with quick chop. It took a while, but it was totally controlled and went beautifully."

Challenges and Tips for Overcoming Them

As with any new technique, proficiency with bimanual microincision phaco comes after working through a learning curve. Dr. Chang suspects that most surgeons making the transition to the technique will find three aspects of it most challenging. First, your second instrument is an irrigating chopper; therefore, it's larger than the chopper you're accustomed to, and you're somewhat tethered by the irrigation tubing. "It's harder to change chopper tips (from vertical to horizontal) as I like to do, so I'm a little more constrained as far as that second instrument," he explains. "Certainly you can overcome that, but it makes using the second instrument a little more cumbersome." Working through the tighter wounds also reduces instrument maneuverability.

Second, the 20-gauge instruments can tend to stretch the incisions so they don't seal as well as the typical paracentesis. He's solved that by using a trapezoidal 1.2/1.4-mm diamond blade. And third, Dr. Chang thinks performing a capsulorhexis through the small incision can be tricky for some surgeons. He uses a bent 25-gauge needle with irrigation, but those more comfortable with forceps will find that part of the procedure a little more technically challenging.

Dr. Fishkind currently does about 25% of his cataract cases bimanually with microincisions. A big reason he's staying at that percentage for now is the added time procedures take. How much more time depends on the firmness of the cataract. "It's an exponentially increasing amount of time," he says. "Soft cataracts are pretty short. A little bit harder takes a little bit longer. Much harder takes much longer." He estimates that a 4-plus cataract takes 10% to 15% more time, true time in the anterior segment, than it would with coaxial phaco. "For the real hard cataracts, you can do it, but it may be counterproductive at that point," he says.

On the other hand, he does expect that time to decrease with more experience. Dr. Hoffman feels the same way. He has an approximately 3-minute difference between the standard and microincision techniques, and expects that to narrow.

Once you know what to expect with the new technique, these tips can help ensure success:

- To keep spray from deflecting off the phaco needle hub, cut the shaft off the irrigating sleeve, and slide the base on top of the needle hub, as Dr. Packard suggests.

- To avoid reverse flow siphoning, put some type of cap over the vacant irrigating hub on the phaco handpiece.

- To avoid rupturing the capsular bag, remove some viscoelastic before hydrodissection. Avoid high-viscosity visco because it can be difficult to remove.

- Achieve good free rotation of the endonucleus using hydrodelineation.

- Impale the phaco needle as deeply as possible into the endonucleus for the first chop.

- Avoid directing infusion flow at the phaco needle, which will dislodge fragments purchased on the tip. "Hold the irrigator above and a little in front of the phaco needle," advises Dr. Fine. "And if you want to use the chopper for something that's occluding the tip, approach the tip from below and behind."

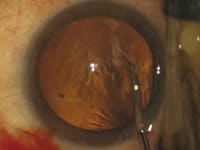

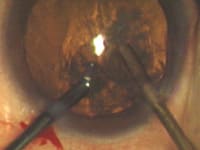

- Dr. Hoffman recommends placing the phaco needle in the eye before the irrigating instrument. He finds that makes insertion easier because there is no fluid pressure working to close the phaco-needle incision. Dr. Olson does the opposite. (See the images on pages 50 and 51.)

- To avoid wound burn, know that some phaco technologies are less forgiving than others, and follow the same rules you always have (don't use a lot of continuous ultrasound or pulse, use brief periods only when you need to, make sure you have good flow, keep your occlusions brief and/or back off the energy).

- To avoid snagging Descemet's, Dr. Fine recommends inserting your chopping instrument upside-down and turning it upright once the tip has cleared the internal incision.

- Because there is very little viscoelastic egress, avoid overfilling the chamber.

- To "warm up," do bimanual I/A in some coaxial cases.

- Dr. Fishkind believes it's helpful to be able to move between various techniques, depending on the hardness of a cataract. "You'd do that for any phaco case," he says, "but I think with bimanual you have to be a little more facile at switching. There's less ability to move the instruments; you have to move them through the incisions kind of like a piston. If you try to move them from side to side, the wound becomes an oarlock and causes distortion of the cornea and you can't see well."

Moving Closer to the Perfect Procedure

As their comments indicate, all of the surgeons who have performed bimanual microincision phaco consider it a worthwhile procedure that will likely grow in popularity once ultrathin IOLs are proven to be safe and effective. When that happens, a whole new set of possible benefits will emerge.

"Patients will be fully mobile and back to regular activities, including strenuous activities, immediately post-op," Dr. Fishkind predicts. "And the hope is that these tiny incisions, once sealed, will reduce the risk of endophthalmitis and other potential postoperative problems." And if less inflammation and better initial visual acuities turn out to be among the results, it will be a boost for patient satisfaction.

"Once we have lenses that can take advantage of the microincisions, there will be a landslide move to the procedure," says Dr. Olson. In the meantime, Stephen Pascucci, M.D., recommends that every cataract surgeon acquire the skills to master microincision phaco, which are the skills that will be necessary for the future of cataract removal.

|

Choosing Your Settings |

Bimanual microincision phaco can be performed on any of today's machines that incorporate energy reduction features. "But you've got to have a good feel for your machine's capabilities, particularly with respect to incisional heat," says David F. Chang, M.D. "It's all about the margin of error." "And you have to do a little work to find the parameters that work best to maintain chamber with the machine you're using," says William Fishkind, M.D. The examples below give you an idea of what settings are being used. In general, irrigation inflow is reduced, so to maintain a stable chamber, bottle height must be higher and vacuum level must be lower than with coaxial phaco. David F. Chang, M.D., with the Sovereign and WhiteStar (The technique can also be performed with the Sovereign Compact.)

"On the aspiration side, I've been using STAAR Surgical's disposable flow restrictor, Cruise Control. It significantly reduces surge, which has allowed me to use essentially the same vacuum setting as I use for coaxial." I. Howard Fine, M.D., with the Legacy and NeoSoniX

Howard Fine, M.D., with the Bausch & Lomb Millennium and Concentrix pump

Richard Packard, M.D., with the Infiniti

Mark Packer, M.D., with the Sonic Wave

These settings can be used with either the Cruise Control or STAAR's Coiled SuperVac tubing. Stephen Pascucci, M.D., with the Dodick laser phaco system

|

|

Bimanual Microincision Phaco: Key Steps |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

Incision size is critical when you're performing bimanual microincision phaco. An incision that is too large compromises chamber stability. An incision that's too tight restricts the movement of the instruments. Use a keratome specifically sized to your instruments, Randall Olson, M.D., advises. If you're using 20-gauge instrumentation, your incision should ideally be 1.2 mm to 1.3 mm when your procedure is finished. "I wouldn't go larger than 1.4 mm," says Dr. Olson. "If you do, it's likely to be a leaky wound. Your chamber will not be as stable, which is dangerous for capsular breakage, and you'll have the annoying problem of nuclear fragments going toward the wound rather than the phaco needle." Incision length is important, too, he says. "I've found going at the limbus parallel to the iris plane is best. There's less oarlocking and you don't make them too long or too short, which compromises sealing." Richard Hoffman, M.D., points out that an adequately long tunnel is also key to chamber stability, minimal leakage and self-sealing. Most of the surgeons performing bimanual microincision phaco now create a separate incision for IOL implantation, rather than enlarge a stab incision. Dr. Olson, for example, says he's uncomfortable having a 1.2-mm segment in an IOL incision that's close to 3 mm. He found leakage was likely in that scenario. David F. Chang, M.D., creates both of his stab incisions with a 1.2/1.4-mm diamond trapezoid blade. He explains why: "Normally, when we go straight in and straight out with the keratome, the entry and the exit of the incision are the same width. But with the trapezoid blade, the entry through Descemet's is smaller than the exit through the peripheral-most part of the cornea. Therefore, there's less tendency for the wound to gape after it's been stretched with the instrumentation, and I have a little more freedom for angulating the instruments within the eye without causing corneal striae and oarlocking." |