Managing

Medicare Fee Reductions

Making the right kinds of changes can help a retinal

practice stay in the black.

BY G. PHILIP MATTHEWS, M.D., PH.D., KITTY VENKATARAMAN, M.S., PH.D., AND

DAVID COVERT, M.B.A.

Since January 1, 1992, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has administered physician payment services through a "prospective payment system" under section 1848 of the Social Security Act. The Act requires physicians to be paid under a fee schedule based on national uniform relative value units (RVUs), which are supposed to reflect the resources used when providing a given service.

|

|

|

|

PHOTOGRAPHER: DAVID GAZ |

|

Unfortunately, since the inception of the prospective payment system, a number of factors, including revisions in payment methodologies, have caused a shift in reimbursement levels and a lowering of Medicare fee schedule (MFS) values. At the same time, Medicare budget neutrality provisions and practice expense RVU changes have marginally favored office-based medicine over surgical procedures. This has caused overall fees to decline among various medical specialties. (For example, ophthalmologists experienced a significant reimbursement reduction as a result of the diagnostic ophthalmoscopy correction in 2002.)

Overall, the reductions in all medical specialties added up to a 5.4% decline in the 2002 Medicare fee schedule. This adverse impact may continue in the future if a reduction in MFS for specific ophthalmology CPT codes becomes a reality.

To maintain profitability in the face of declining reimbursements, it's imperative for physicians -- especially retinologists -- to re-evaluate how their clinical practices are organized and managed. Changes in these areas could potentially offset reimbursement cutbacks.

With that in mind, we decided to develop a retinal practice reimbursement model that would do two things: First, it would illustrate the economic impact of 2002 Medicare fee reductions on practice revenue compared with 2001 revenue. Second, it would demonstrate how practice reorganization could work to maintain revenue growth in the future, despite these kinds of changes.

Working Out the Numbers

The practice we based our calculations on was a solo retinal practice encompassing two office exam/treatment centers and two hospital operating rooms. (Obviously, the case mix and revenue mix from this solo practice may not match that of your own practice, but we believe the general principles established here make sense for the majority of ophthalmology practices.)

We reviewed office and surgical reimbursements during the period January 1, 2001 through December 31, 2001. Because more and more commercial insurance carriers are reducing their payment schedule to parallel Medicare rates, we recalculated the revenue generated by reimbursement claims -- including those paid by commercial insurance -- using the 2001 Medicare physician fee schedule rates. (The MFS rates used in our model were based on carrier and locality-specific rates for the retinal practice we were studying.)

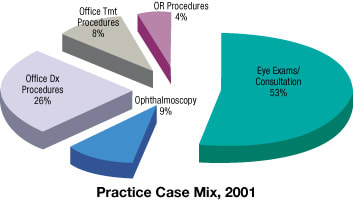

- 53% of the patients came in for standard eye exams and consultations

- 26% underwent office-related diagnostic procedures

- 9% required ophthalmoscopy

- 8% underwent office-related surgical procedures

- 4% underwent OR surgical procedures.

Next, we developed a 2002 reimbursement model using the same case mix as in 2001, but with 2002 MFS rates. We then compared the 2001 revenue with estimated revenue for 2002 under three different scenarios:

- First, we modeled estimated revenue assuming zero growth in patient volume in 2002.

- Second, we estimated revenue if the practice experienced 3% base growth in office and OR patient volume.

- Finally, we estimated 2002 revenue assuming that the practice experienced 3% base growth in office and OR patient volume, plus an additional 10% increase in office time and patient volume.

For purposes of this study, we defined a work year as 44 weeks. To create the hypothetical 10% increase in office time in our third scenario, we restructured the OR schedule (which was 2 half-days per week) so that we could add 2 additional days of office time every month.

To do this, we converted one half day of surgery each week to one half day of additional office exam time. However, it was important that this change not undercut surgical volume. To maintain the same surgical volume in 2002 as in the previous year, we extended the length of the surgical schedule during the remaining half day session each week. The end result was the equivalent of adding 22 days to the 44-week year -- a 10% increase.

Other factors we accounted for included:

- All pneumatic retinopexies in 2001 were performed as hospital procedures.

- The practice did not perform photodynamic therapy (PDT) in 2001.

- Hospital in-patient consultations and emergency room visits were excluded from this model because of the variability in treatment volume.

- We assumed that all laser (argon and YAG) treatments were performed as outpatient office procedures.

Here's how the numbers came out:

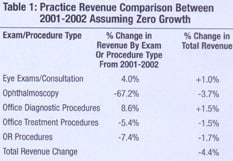

If patient volume stayed the same. Table 1 (below) illustrates the practice revenue in 2001 and 2002, assuming zero growth in patient volume. The most striking change is the drop in ophthalmoscopy reimbursement for 2002 (CPT codes 92225, 92226); this largely accounts for the overall drop in revenue.

On the positive side, revenue from eye exams and consultations increased 4.0%, but this wasn't enough to offset the decline in both office-based procedures (a 5.4% reduction) and OR surgical procedures (a 7.4% reduction). The overall effect of all these changes is a 4.4% drop in reimbursement revenue -- not good news for any practice.

The next two charts show how the change in Medicare reimbursement levels between 2001 and 2002 affected the percentage of revenue derived from each category (assuming the case mix stayed the same): During both years, the percentage of practice revenue from OR and office-related surgical procedures stayed the same (23% and 28%, respectively). Eye exam/consultation and office diagnostic procedure revenue increased; they accounted for 2% more of the total revenue in 2002. However, the revenue from ophthalmoscopy -- 6% of the total in 2001 -- dropped to only 2% of the total in 2002.

|

|

|

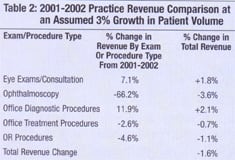

If office and OR patient volume grew 3%. Table 2 (below) shows the practice revenue comparison assuming 3% base growth in office and OR patient volume for 2002. In this case, the overall reduction in revenue is only 1.6%. (Percentages shown have been rounded.)

If office time and patient volume increased 10%. (This increase is in addition to the 3% base growth in office and OR patient volume). Table 3, below, illustrates the result of a dramatic increase in patient volume and more time spent with patients. In this scenario, there's an overall increase in revenue of 6.0%.

Other changes could also help offset reimbursement cuts. Some doctors may choose to de-emphasize elective OR surgical procedures and focus more on office procedures that have higher Medicare reimbursement levels. (Of course, this strategy may be of limited use if elective OR surgical procedures contribute a significant portion of your practice's revenue.) Also, new diagnostic and treatment procedures should provide new sources of revenue.

No More Status Quo

The conclusion is clear: Thanks to the reduction in reimbursement rates for ophthalmoscopy and surgical procedures, a retinal practice that maintained the same mix and level of office and OR services in 2001 and 2002 almost certainly lost a significant percentage of revenue in 2002.

On the other hand, our numbers show that there is hope. Small but significant increases in office time and patient clinic volume can more than compensate for these losses, as long as OR surgical volume is maintained.

In all fairness, the options for maintaining profitability we've discussed here do have limits. Our model assumes that 3% patient growth can be managed by the current office capacity, and that further increases in office patient volume are possible by reallocating OR time to the office. Even if your practice can make this kind of change, it's probably unreasonable to think you can continue to use this strategy without expanding your office staff.

The bottom line? Maintaining the status quo is no longer an option if you hope to maintain an economically sound practice. All of us need to make it a policy to continually evaluate our practice management and look for ways to adapt in this ever-changing reimbursement environment.

Dr. Matthews is in private practice in the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex. He specializes in treating vitreo-retinal disease. Kitty Venkataraman and David Covert plan and conduct research studies for the Health Economics Department at Alcon.