New Drugs Take on Wet AMD

Delivered into or behind the eye, they inhibit

new blood vessel formation.

Clinical trials have been promising.

BY JERRY HELZNER, SENIOR ASSOCIATE

EDITOR

With an estimated 1.6 million Americans already afflicted with the wet form of age-related macular degeneration (AMD), and 200,000 new cases being diagnosed each year, it's no surprise that some of the biggest companies in the pharmaceutical world are now trying to develop new and better treatments for this sight-robbing disease.

The opportunity is great. As the huge baby boomer cohort ages, the number of individuals with wet AMD will continue to mount, with some experts predicting as many as 6 million cases in the United States by 2030. And the only currently approved pharmaceutical treatment for wet AMD is verteporfin for injection (Visudyne), which only slows the progression of the disease.

In this article, I'll examine how three wet AMD drugs that are delivered into or behind the eye are progressing in the continuing battle against the disease. These are by no means the only potential treatments for wet AMD -- gene therapy is one promising area for the longer term, and other modes of treatments are currently being explored -- but these three are the furthest along in trials and have spawned the most optimism among clinicians.

|

|

|

|

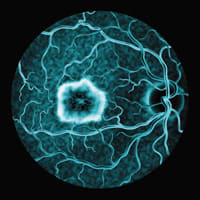

ILLUSTRATION: JOEL & SHARON

HARRIS/ILLUSTRATIONONLINE.COM |

|

Encouraging Trials

Today, the three new drugs, each backed by at least one deep-pocketed pharmaceutical giant, are in late-stage clinical trials for the treatment of wet AMD. And though the compounds are very different, each aims to stop the unwanted blood vessel formation (which occurs through a process called angiogenesis) characteristic of wet AMD. Trial results thus far have been promising for each of the three.

If this were a horse race, the entrants would be named Lucentis, Macugen and Retaane. And the owners would be, respectively, Genentech/Novartis, Eyetech/Pfizer and Alcon.

"It's a bit like a horse race," says Henry Hudson, M.D., F.A.C.S., of Tucson, Ariz., an investigator for Alcon's anecortave acetate for depot suspension (Retaane 15mg). "Except we don't know yet if we have a Seabiscuit here."

Both ranibizumab (Lucentis) and pegaptanib sodium (Macugen) fall into the class of drugs known as antiangiogenic agents, or more specifically, anti-VEGF agents. They act by binding to the free-floating protein known as Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), which is responsible for new blood vessel growth in eye diseases. By binding to the VEGF, they inhibit the formation of new and leaky blood vessels in the macula. Both drugs are administered by intravitreal injection directly into the eye.

Retaane also works to inhibit new blood vessel formation, but it's an angiostatic steroid. It's delivered directly behind the macula with a specially designed cannula.

In a phase II/III trial of Retaane, 74% of treated patients with various forms of wet AMD had stable or improved vision after 24 months.

In a phase Ib/II clinical trial, 97.5% of 40 patients with various forms of wet AMD who received monthly injections of Lucentis had stable or improved vision after 210 days, with 45% of those improving by 3 lines or more on an EDTRS chart.

In a large phase III study of Macugen, which has been "fast-tracked" by the FDA for possible early approval, 33% of the patients with various forms of wet AMD who were injected with Macugen every 6 weeks showed stabilized or improved vision after 54 weeks.

All three drugs have demonstrated excellent safety profiles, according to investigators, and all three continue to be the subject of clinical trials. One of the more interesting trials will begin in January when patients with advanced dry AMD who are at risk of progressing to wet AMD will be given Retaane in a groundbreaking 4-year study. The FDA has already "fast-tracked" Retaane for this indication.

Early Trials Were Halted

Despite the enthusiasm surrounding all three of these new therapies, an optimism that appears warranted given the early results, it's worth noting that this isn't the first time drugs that inhibit blood vessel formation have been tried against wet AMD.

In the 1990s, antiangiogenic agents burst into public consciousness, as researchers were able to validate the pioneering work of Judah Folkman, M.D., and his team at Childrens' Hospital in Boston. In the 1970s, Dr. Folkman had developed a theory that solid, malignant tumors could literally be "starved" to death if the blood vessels that fed them could be killed off. Once the basic concepts of angiogenesis inhibition to control disease had been accepted, it didn't take long for researchers to conclude that these agents might be useful for treating wet AMD, as well as cancer.

"Much of the research in antiangiogenic agents is translatable from cancer to wet AMD, says Jerry Chader, Ph.D., M.D., chief scientific officer for The Foundation Fighting Blindness. "It's the same process in that your goal is to prevent abnormal blood vessel growth."

One of the first companies to try developing an antiangiogenic drug as an AMD treatment was Agouron Pharmaceuticals. The company developed an antiangiogenic inhibitor called AG3340 (Prinomastat), which was used against wet AMD in an early-stage clinical trial and then dropped from commercial development. Another drug that displayed antiangiogenic properties, thalidomide, failed as an AMD treatment in one small study because patients experienced intolerable side-effects such as drowsiness, constipation and neuropathy.

The lack of success with these, and several other antiangiogenic agents, stemmed the momentum for this approach for a time, but the spectacular recent results achieved by Genentech's bevacizumab (Avastin) against colorectal cancer have rekindled interest in compounds that inhibit blood vessel formation. Avastin is widely expected to be the first antiangiogenic agent approved by the FDA, and its chemical composition is closely related to that of Lucentis.

"Lucentis is actually derived from a fragment of Avastin," says William Li, M.D., president and medical director of The Angiogenesis Foundation, which acts as a worldwide information center for angiogenesis research. "It's important for ophthalmologists to recognize that many lessons learned from cancer patients concerning the safety and efficacy of antiangiogenesis treatments are going to be useful in helping AMD patients. For ophthalmologists, the fruits of the knowledge and experience already gained in this area of medical research are ready to be picked."

Looking Ahead

Whether the next approved treatment for wet AMD is an angiogenesis inhibitor, an angiostatic steroid or something else, it appears certain that Visudyne's future will be as part of a combination therapy used in concert with another drug.

Paul Hastings, the CEO of Visudyne co-developer QLT Inc., has said that Visudyne "makes sense" as part of a combination therapy "because the anti-VEGF drugs are designed to stop the formation of new blood vessels and Visudyne acts to stop current leakage by sealing blood vessels. If you look at the way diseases are treated these days, there's more emphasis on finding combinations that are more effective than a single agent."

Others share Hastings' belief. In Lucentis and Macugen trials now under way, the new drugs are being used in combination with Visudyne to determine if combination therapy is more effective than single-agent therapy. In the oncology world, combination strategies using antiangiogenic agents have led to better clinical results.

No one can predict the future, but the large and growing size of the patient population, coupled with the fact that current treatment options for wet AMD patients are very limited, almost guarantees that pharmaceutical companies will place a high priority on this area of research. With some of the biggest names in the pharmaceutical industry now focusing their efforts on finding treatments for wet AMD, hopes have never been higher for a true breakthrough.