New Avenues in

Glaucoma Diagnostics

Ten specialists discuss the impact of the latest tools.

BY CHRISTOPHER KENT, SENIOR ASSOCIATE EDITOR

In this article, we present the results of extensive discussions with ten glaucoma specialists, who registered their opinions about whether these new tools currently have a place in everyday clinical practice, and whether they're likely to change today's standard of care.

Some envision a future in which doctors will use a combination of functional and structural tests, perhaps tracking different parameters at different stages of the disease. Few aspects of the topic are without debate.

The Strengths of SITA

One point that everyone we interviewed agreed upon is that the SITA Standard algorithm for perimetry is rapidly becoming the new gold standard for visual field testing. "The SITA algorithm essentially gives you the same amount and quality of information that was given in the full threshold technique, but it takes half the time," says Robert Ritch, M.D. "Our patients hate doing visual fields, and the length of the test is the main reason."

"Standard full-threshold perimetry often requires longer testing time because of the amount of data obtained," explains Andrew Rabinowitz, M.D. "In most cases much of that data isn't clinically pertinent. In contrast, SITA obtains maximum information in a minimum of time. If it's financially feasible, I think most physicians should upgrade to SITA."

The experience of Robert N. Weinreb, M.D., has been similar. "SITA provides a shorter test time, a less variable test result with narrower confidence limits, and higher patient satisfaction as well. It's becoming the standard for testing visual fields, and most likely, doctors in clinics who are not using it at the current time will be upgrading at some point."

Donald Budenz, M.D., was involved in collecting the data for the age-matched normative database for SITA. "We were one of the first groups to use it, and we've been using it ever since. Most of our patients complain about the length of the visual field tests, and the longer the test, the poorer the responses. We've pretty much replaced full threshold testing with SITA at Bascom Palmer."

Making the Transition

To run SITA, you do need the latest Humphrey Field Analyzer, but Dr. Budenz sees an upside to this. "One great thing about the new Humphrey Field Analyzer is that it will do both SITA and traditional full threshold testing," he says. "That's important because we don't have any software yet to help us compare full threshold results to SITA. If we switch back and forth between tests we can't tell if the patient is getting worse. For that reason, if we have patients who have a glaucoma defect on one or the other test, we prefer to test them using the same program. I use full threshold for patients who've had full threshold in the past."

"When you switch someone from the standard, older test strategies to the SITA, the field will look different," agrees Robert Fechtner, M.D. "It might even look a little better on SITA. In this situation I do two fields relatively close together in time to establish a new baseline. In my experience, patient preference for the shorter SITA test usually makes it worth switching."

Dr. Weinreb also takes at least two SITA tests to create a new baseline. "If you have to compare fields done with full threshold with fields done with SITA, it's best to use the probability plots for comparison. SITA shows slightly better raw thresholds in grayscale values but comparable results on the probability plots."

Michael Motolko, M.D., points out that "It would be nice if we had a glaucoma probability change function, much like the one that exists for standard threshold testing. Everyone has been waiting quite some time for it."

SITA Fast

The SITA program can also be run in a faster mode, but most of the doctors we spoke with felt that this has limited usefulness.

"Studies we've done showed that SITA Fast may lose some visual field information, particularly when diagnosing early field defects," says Dr. Budenz. "When you get too fast, the computer makes too many assumptions about the responses (which is basically how SITA speeds things up). This can lead to underdiagnosing early field defects. The sensitivity of SITA Fast for early defects in our studies was only about 85%, using full threshold as the gold standard. When you're trying to determine whether a patient has early glaucoma or not, you don't want to miss 15% of the data in order to save 2 minutes."

SITA Fast does have its uses, however. "I sometimes use SITA Fast for very elderly patients, or patients who have very poor reliability indices when taking a longer test like SITA standard," says David S. Greenfield, M.D.

Dr. Budenz concurs. "We sometimes use it with children because it's short. Of course, we're not usually looking for early field defects in children; they're a special category."

Dr. Fechtner describes another use for SITA Fast. "When people first take visual fields, there's a learning curve; they do better after two or three fields. If someone is pretty unreliable on their first field, I let them do one or two SITA Fasts just to get accustomed to taking the test."

Frequency Doubling Technology

As you know, frequency doubling technology uses contrast sensitivity testing to assess the function of Magnocellular (M-cell) axons, which carry information regarding contrast sensitivity and short wavelengths. Because they're much sparser than P-cells, which transmit information involving the longer wavelengths, loss of 10% to 15% of M-cells can manifest as a discernable defect when testing with contrast sensitivity or short wavelengths.

"Frequency doubling technology is a very intriguing use of contrast sensitivity testing," says Dr. Fechtner. "The theory behind it is very strong. We're going to need different functional approaches to detect early glaucoma, and that's where tests like FDT or SWAP come in. Frequency doubling is probably a better test for this than our white-on-white standard test."

Harry A. Quigley, M.D., says his research suggests that FDT is a reasonable way to separate people with significant glaucoma damage from normals. "At this point, the major problem is the lack of longitudinal data," he notes.

Dr. Budenz says he isn't convinced that frequency doubling diagnoses glaucoma any earlier than standard white-on-white perimetry, but he uses his FDT unit for screening programs in the community. "It's light -- I can carry it under one arm," he says.

Dr. Rabinowitz sees FDT and SITA as complimentary tests. "FDT provides early insight into M-cell death in the early stages of glaucoma; SITA provides reproducible and pertinent information regarding P-cell death. It makes the most sense to use the two modalities in tandem."

The FDT instrument has recently been upgraded to test a much larger number of points. Dr. Greenfield comments: "This may not only make it a valuable tool for screening and early detection, but also a valuable tool for the detecting of glaucomatous change over time."

However, Dr. Weinreb notes that "The new test patterns haven't been evaluated in large numbers of patients, and there are no longitudinal results with the new versions of the test." Several laboratories, including his, are doing studies to find out more about the clinical utility of the test for following glaucoma.

Dr. Rabinowitz disagrees strongly with the idea that FDT is only useful for early suspects and diagnosis. "If one part of the visual field is already damaged, and you've got the patient's pressure down, do you want to wait until new defects on standard perimetry indicate that the pressure's still not low enough? If a problem remains, you'll know about it years earlier using frequency doubling. I don't believe FDT is useful only for early cases, and I don't think its use should be limited to glaucoma suspects."

Short Wavelength Automated Perimetry

The SWAP test, while monitoring the same axons as FDT, is a very different experience for the patient.

"Patients hate the SWAP test," says Dr. Ritch. "I've taken it. It's hard to see the test spots; everything turns purple. Some patients even feel sick. It's very uncomfortable. On the other hand, it's highly accurate at detecting early defects and subtle progression."

"SWAP really is a tedious test, and you do find abnormalities quite frequently; even normal patients who test with SWAP will have some type of defect," observes L. Jay Katz, M.D. "Because it's so tedious and difficult to do, it's not a type of test I would ask an elderly patient who fatigues easily to take. I use it primarily for patients with suspect optic nerve appearance or elevated eye pressure, but with no defects detected using white-on-white perimetry."

Sanjay Asrani, M.D., agrees. "In its current form, SWAP is too arduous. Nevertheless, it does have the potential of helping in the diagnosis of early glaucoma. And if the test results are normal and reliable, it gives me an added measure of confidence that even if the patient has glaucoma, it's at a very early stage."

Dr. Budenz notes that, as with some other glaucoma detection tools, media opacities such as cataract can cause abnormal responses on SWAP. He also points out that AMD has been found to interfere with SWAP and cause false defect readings. "Although it may very well pick up glaucoma before white-on-white perimetry" he says, "it may be a bit too sensitive."

According to Dr. Quigley, "I think even the originators would agree that the test takes much too long. And when it first came out, the normative database against which your patient was being compared was too perfect, leading to many false positives. In addition, SWAP is a harder judgment for the patient than the white-on-white test. When it takes longer and it's harder to interpret, its difficult to be sure that it's the best thing for patients to use. At the same time, it definitely has potential value."

Despite the drawbacks, Dr. Weinreb says he believes it's important to have a perimeter than can do SWAP. "SWAP is the best-studied of all the visual function-specific perimetric tests. It's more sensitive to early glaucomatous damage, and superior to standard visual fields for following patients over time. In addition, it's useful for following patients with diabetes, optic neuritis, and HIV."

Dr. Weinreb also notes that changes in the latest version are intended to address some of the difficulties with the test. "SITA SWAP, which is a combination of the SITA testing strategy and the short wavelength testing paradigm, has recently been developed and should be available in the near future. The test takes less than four minutes, and it's much easier for the patient because the target spends less time below threshold. It's still more difficult to see the blue/yellow target because our blue/yellow pathways don't have good acuity. But if you explain to patients that they might not see the target clearly, they do quite well with the exam.

"SWAP is useful for all but the most advanced cases of glaucoma or cataract," he adds. "In these cases, we switch the patient to standard visual field testing. In all other cases, SWAP still shows deficits and progression before standard fields do."

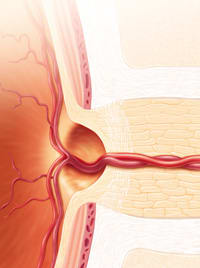

The Role of Imaging Technology

The current options in optic nerve imagers and retinal nerve fiber layer analyzers elicit a host of opinions regarding their use in the clinical setting, including how they stack up for early diagnosis and monitoring. (See also, "Pre-Purchase Pearls," on page 39.)

"These instruments provide quantitative, objective and reproducible information about the optic disc, and/or the nerve fiber layer," says Dr. Weinreb. "Moreover, they can provide information beyond what's obtainable from a clinical examination. They're not only useful for diagnosing disease and following patients for progression; they're also useful in particularly problematic cases, for confirmation of clinical findings."

Several specialists say they currently use these technologies in a confirmatory role. "Imaging mainly confirms what I'm already thinking," says Dr. Katz. "It's only one piece of the diagnostic equation. Having that additional piece of information usually just makes me feel more firm about my diagnosis."

Dr. Asrani says that he uses these instruments as an adjunct to optic nerve head visualization; he doesn't believe doctors should be routinely using them for earlier diagnosis. "Generally, I use these instruments in younger patients when I'm suspicious of glaucoma. In established patients, I use them to help me confirm the stage of their glaucoma by assessing the extent of tissue loss. They also help me educate patients regarding their eye status -- especially when treatment is warranted in the absence of visual field defects."

"Their real value lies in their ability to detect change over time," adds Dr. Motolko. "Diagnosing glaucoma progression -- ideally before significant field loss has occurred -- is the promise of this technology."

As with FDT testing, Dr. Rabinowitz disagrees with the impression that the imaging instruments are primarily only useful for suspects and early cases. "I believe their ultimate utility will favor the advanced cases far more than the suspects and early cases," he says.

"My practice involves a lot of older and more advanced cases, and I find these instruments at least as useful in these cases. I see more variability when imaging glaucoma suspects or normals than I do in advanced cases -- more data that has to be thrown out because I can't account for it -- and using the HRT or GDx in advanced glaucomas, I get fewer results that are contrary to other findings.

"The impression that these technologies are less useful in middle to late glaucoma is based upon a far smaller set of patient data than we have for early to middle cases. Coding is part of the problem. Many doctors don't image middle to late glaucoma patients simply because it's not billable. I believe that if coding becomes appropriate for middle to late usage, a lot of doctors will discover the same thing I've already observed."

The doctors we interviewed also made some comments specific to four of the imaging systems:

Heidelberg, HRTII. "The HRT is the instrument that hasn't changed in the longest period of time," observes Dr. Quigley. "As a result, there's the most longitudinal data available on it."

Dr. Greenfield uses the HRT to image many of his patients. "The HRTII obtains highly reproducible measurements of optic nerve topography, and it has very sophisticated software to detect glaucoma progression that's been validated in several studies," he says. "There's evidence that scanning laser ophthalmoscopy may even be more sensitive for detecting glaucoma and progressive changes in the optic nerve head than glaucoma experts." In addition, updates to the HRT have extended its usefulness from glaucoma to retina and cornea as well.

Carl Zeiss, Stratus OCT. "I think the OCT is an excellent instrument and will continue to improve in the future," says Dr. Ritch. "The resolution is just fantastic. Right now, it's best for retina, but we're using it for research, looking at the optic nerve and measuring the thickness of the retinal nerve fiber layer."

In May, the FDA approved a nerve fiber layer normative database for the Stratus OCT, which improves its usefulness in glaucoma diagnosis and monitoring.

Laser Diagnostic Technologies, GDx VCC. "Both the GDx and OCT are extremely useful instruments in my practice," says Dr. Greenfield. "They allow me to evaluate the thickness of the retinal nerve fiber layer, which in my experience is an excellent indicator of early structural change in glaucomatous optic neuropathy. I also think they show considerable promise for the detection of change over time."

Dr. Fechtner says he uses the GDx VCC in many patients, including those who have anomalous optic nerves and for glaucoma suspects. "The nerve fiber layer probably has less variability from individual to individual than the optic nerve itself," he explains. "It's an important place to look for subtle early abnormalities."

Talia, RTA. "The RTA is unique in that it looks at the retina instead of the optic disc, but there's considerable evidence that this should be able to detect glaucomatous damage," notes Dr. Quigley.

Dr. Katz agrees. "The Talia instrument has introduced the concept of measuring the macular area, where you find the highest concentration of ganglion cells. This may turn out to be an earlier indicator of glaucoma when it thins out. In fact, recent studies have provided some support for this."

Regarding this entire category of devices, Dr. Ritch cautions that doctors shouldn't depend on them too much. "I heard about a woman in her 40s whose pressures, discs and visual fields were normal. She was treated with medications, laser and nearly a trabeculectomy because of a defect found on a GDx test," he says. "This is what you have to worry about, people using these instruments as gospels. They're not. They just supply more data for you to fit into the picture."

Dr. Weinreb agrees. "It's important to place these tests in the context of an accurate and thorough clinical examination. Basing treatment on information gleaned only from a single instrument test would be a misuse of the technology. At the current time they're meant to enhance an informed clinical examination, not to replace it."

What Lies Ahead?

"The future will be very exciting," says Dr. Weinreb. "There will be less reliance upon subjective visual function testing, and increasing use of objective and quantitative techniques for assessing the optic disc and retinal nerve fiber layer. Most likely, one single test won't prevail as the gold standard for diagnosing or following glaucoma. I believe we'll use a complement of functional and structural tests, combining the information with novel data analysis schemes."

Dr. Fechtner agrees. "I think we'll be using functional and structural testing to follow different parameters at different stages in the disease," he says. "Hopefully we'll be able to detect progression by spotting less dramatic change than it often takes today. I want to know that somebody's getting worse when they've gotten a little bit worse, not when they've gotten a lot worse."

|

Pre-Purchase Pearls |

We asked our panel of ten glaucoma experts what doctors should take into consideration before deciding to buy or lease a new glaucoma diagnostic tool. Almost everyone recommended reading the available clinical data, talking to colleagues you respect who have used the technology -- and, of course, checking for reimbursability in your area. Other suggestions included: Weigh the financial impact. Dr. Quigley advises remembering the seemingly small costs associated with using an instrument. "Don't just take the service contract into account," he says. "Factors like the cost of cartridges for the printer can add up fast." How long the test takes is also a factor. If you have a high-volume practice, you might be able to scan 30 patients in a day with one instrument, but only 20 with another. "These tests are all billed under the same reimbursement code at a fixed revenue value, so the number of tests you complete correlates directly with the amount of reimbursement you can receive," says Dr. Rabinowitz. Consider what you need the technology to do. "No one instrument is helpful in the full gamut of glaucoma problems," says Dr. Motolko. "If the majority of your patients are early to mild glaucoma, or glaucoma suspects, you should be considering a very different technology than if you're dealing with moderate to severe glaucoma most of the time." Look at ease of use. "Consider how easy it is to acquire and analyze the data," suggests Dr. Weinreb, "not only for diagnosis with a baseline examination, but in terms of comparing with future examinations." Dr. Weinreb also points out that a reduced need for dilation can be an important factor if you plan to screen for glaucoma in a large group of individuals. Consider patient-friendliness. In a "difficult" test such as SWAP, this clearly must be balanced against the value of the data. But avoiding dilation is also a high priority for many patients, as is the length of time required to take the test. Consider the "common language" factor. Dr. Rabinowitz points out that an instrument that's widely in use has an advantage by virtue of its acceptance. "If I'm sharing a patient with a doctor in Minnesota because the patient spends half the year here and half the year there, we can't compare test data unless we use the same instrument. So it makes sense to consider which technologies are already most widely used." Plan for possible obsolescence. "Find out whether there will be an upgrade pathway if the technology changes again in a few years," suggest Dr. Fechtner. "Based on past experience, this seems likely!" Weigh your need for portability. "Some of these devices can be moved; others can only be operated at one site," points out Dr. Rabinowitz. Check your comfort level. "Many ophthalmologists, including glaucoma doctors, have much greater comfort assessing the anatomy of the disc than the anatomy of the nerve fiber layer, despite the usefulness of the latter technology," says Dr. Rabinowitz. He advises doctors who are thinking of investing in a nerve fiber layer analyzer to be sure they're willing to deal with less familiar territory. Be sure you really need one. "Nobody can be faulted for not having any of these machines, including SITA," says Dr. Katz. If you're doing standard, full-threshold white-on-white perimetry, and you have a nice photograph of the optic nerve, that's still state of the art care." Dr. Ritch agrees. "It's great to have an asparagus fork and an oyster fork, but I can still make my way through six courses with a plain old fork." Keep your perspective. "Doing a detailed clinical exam and learning to interpret the results of these tests," notes Dr. Quigley, "is probably much more important than which test you're using."

|

|

Stereo Photographs vs. Electronic Imaging |

Traditionally, the gold standard for optic nerve imaging has been studying a photograph of the optic nerve. Asked how the new optic nerve imagers and retinal nerve fiber layer analyzers compare with this, our experts voiced a wide range of opinions. "Stereo photography is probably still the gold standard," says Dr. Quigley. "On the other hand, how much patients like or dislike a test is an important factor to consider. All of the new laser devices are much easier on patients than flash photography, which patients really, really dislike because of the bright flash. With laser instruments, the patient doesn't even notice anything happening. And not having to dilate the pupil is another significant advantage. "Also, you can get a picture from those laser imagers substantially more often than you can get a decent photograph of the back of the eye. I can sometimes capture an image even though I can't see the disc clinically." "The current standard of care for structural assessment of the glaucomatous optic nerve is still a stereoscopic optic nerve photograph," says Dr. Greenfield. "However, I'm using this less often because of the subjective nature of the assessment, and because of the required dilation, problems with media opacity and the subtlety of change. In eyes with advanced disc damage, disc photographs are useless in the detection of progressive neural rim loss. "I think the gold standard will ultimately change to a quantitative structural assessment of the optic nerve and the peripapillary nerve fiber layer using the new technologies. Of course, we need more prospective longitudinal studies before such a paradigm shift can occur in a meaningful way. Nevertheless, in the meantime I think it's essential to use these instruments in the routine care of glaucoma patients, to help detect glaucoma and progression at the earlier stage. A growing body of knowledge supports the fact that the structural measurements generated by these technologies correlate very well with the disease process." Dr. Budenz says he doesn't use any of the nerve analyzers clinically. "None of them have been proven superior to optic disc photos and visual field analysis for diagnosing glaucoma or following progression. The American Academy of Ophthalmology hasn't recommended that you follow your patients with one particular technology, for the same reason." Dr. Ritch holds a similar view. "If I think a patient's visual field has progressed, I'll take a disc photo and then project it onto the wall along with the old photo in a second projector, making the images about a foot in diameter. I can then examine every detail, looking for subtle changes in vessel position or the neural rim. After doing this hundreds of times over the years, I find it an extraordinarily accurate method of assessment, more so than what I see with the imaging instruments. "However, the imaging instruments are good for confirming suspicious findings in glaucoma suspects. Future advances, particularly more longitudinal data and the development of reliable change criteria, should improve their reliability. This will be a great advantage for the general ophthalmologist, who may not feel that secure looking at subtle changes or subtle findings in a disc." Dr. Katz has noted a gradual shift toward the newer technologies. "When I talk to people around the country, many have switched to just imaging; they don't perform photography any more," he says. "Patients accept imaging much more readily than photography. Data acquisition is simple, and it's often helpful as a patient instructional tool as well. For several years I tried to do both, but it's difficult to manage, so now I don't do disc photography except for the exceptional case." Dr. Fechtner still considers simultaneous stereo photography of the optic nerve to be his personal standard. "I take photos of all my glaucoma patients," he says. "All of the large clinical trials have been based on optic nerve photography, because it's been around for 20 years. None of these imaging devices were around 20 years ago, and I'm not sure any of them will be recognizable 20 years from now. At the same time, looking at the optic nerve is, at best, a subjective way to try to assess damage. I do think we're at a point in our evolution of glaucoma care that we need to be more rigorous about structural evaluations. "I'd still encourage practitioners to get at least one set of baseline photos of every glaucoma suspect," he adds. "If every glaucoma patient walked into my office with disc photos taken when they were 18, my job would be a lot easier." Dr. Fechtner adds: "I think the structural tests are going to extend our senses far beyond what we're able to detect by looking at the optic nerve. Of course, the imaging technologies are still at a relatively early stage. I don't believe that practitioners are doing their patients a disservice if they haven't yet adopted one of them. "Eventually, one or more of these instruments will have passed all of the burdens of proof, and we'll be imaging all of our patients," he concludes. "I just can't predict which one it will be!"

|

|

The Multifocal

VEP: |

Among the newest technologies hoping to improve our ability to diagnose and follow glaucoma is Multifocal Visual Evoked Potential, or mfVEP. This technology detects problems in the visual field by monitoring electrical activity at 60 locations in the visual cortex while the patient stares at a pattern. (Areas with a visual field defect cause the amplitude of the response to be smaller.) While similar to the concept of a visual field test, this test is totally objective. Two instruments using this technology are currently available: VERIS by Electrodiagnostic Imaging and ACCUMAP by Objective Vision in Sydney, Australia. "The main advantage of mfVEP is its objectivity," explains Dr. Ritch. So far, clinical studies have shown good correlation between mfVEP and visual fields. Some clinical data suggests that it might be able to detect glaucoma earlier than a standard visual field. It should be particularly useful in patients with unreliable or borderline visual fields, and it appears to be useful in neuro-ophthalmology cases such as MS, optic neuritis, and ischemic optic neuropathy. "It's still being tested clinically to see where it fits into the scheme of things. We're hopeful that this may even replace visual fields someday, as an objective test where the patient doesn't have to respond." Dr. Weinreb says the UCSD Hamilton Glaucoma Center is one of four sites participating in a multicenter study in the United States.

|