Implementing a

Strategic Plan

Creating the plan is only half the battle. Here's how to take yours from theory to

reality.

By Bruce Maller

Creating an effective strategic plan for your practice is crucial if you hope to prosper in the midst of today's economic uncertainties. (For a brief summary of how to create a strategic plan, see "Creating a Strategic Plan: A Quick Review" on page 116.) However, the thing that really "separates the men from the boys" in strategic planning is implementation.

Creating your action plan

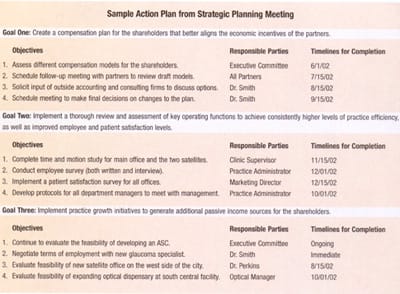

The final business to be concluded in the meeting that generates your strategic plan is to translate the goals and objectives you've decided on into an action plan. The action plan specifies who is responsible for each item on the list, and when you expect that item to be completed. (Without having a designated "owner" assigned to a task, it's difficult to establish accountability measures and reward systems.)

The three charts on the next page specify how one hypothetical practice intends to achieve its chosen goals. As you can see, the plan has three major goals, each with a number of specific objectives, written in clear, actionable language. A responsible party has been assigned to each objective, along with a timeline for completion.

Implementing your action plan

Several factors are necessary if your practice is going to successfully implement your action plan:

- physician leadership and commitment to the plan

- buy-in from management and staff

- making sure that responsible individuals are equipped to manage their tasks

- having a financial plan in place that incorporates the basic framework of the action plan

- periodically evaluating how successful you've been in achieving the goals outlined in your plan.

Let's look at each of these more closely.

Physician leadership

A physician has two key roles to play in the strategic planning process:

Role #1: Orchestrating implementation of the plan. Many physicians -- who may have had little formal training in business -- are insecure about taking a leadership role in the strategic planning process. Sometimes this is for good reason: The typical physician owner of a practice who finds himself in this position is faced with many difficult decisions, and he may not have enough information (or the right kind of information) to make an informed decision.

In this situation, the best strategy is to approach these issues with a certain level of humility. Admitting that you don't know and asking for help or advice is far better than embarking on a venture on the basis of a "gut" feeling or inadequate information.

Solicit the opinion of colleagues or trusted advisors before rolling out any major initiatives.

Role #2: Serving as educator and motivator. It's the physicians' job to convince all stakeholders of the importance of the planning process.

For example, following a strategic planning meeting, physician shareholders should meet with the entire staff to educate them about the process and the plan. They should also make it clear how the staff will benefit from the plan -- i.e., how rewards will be tied to achieving plan goals and objectives.

As a physician, you may be tempted to delegate responsibility for communicating plan details to the administrator or managers, but I recommend resisting that temptation. Employees want to hear the message directly from you.

|

Who's in Charge? |

|

Someone -- generally the lead physician or practice administrator -- should be assigned overall responsibility for the plan. The person chosen is often determined by practice size and governance structure. For example, a large practice with more than 10 physician shareholders might give overall responsibility for the plan to the executive committee of the board. On the other hand, a group practice with two to five doctors, where no single physician provides strong leadership, might assign this responsibility to a practice administrator. The important thing is to choose someone who:

If a practice administrator assumes this responsibility, he or she must provide progress reports to the board on a regular basis. These progress reports should include the action plan with notations showing the progress made on each initiative.

|

|

Getting buy-in from management and staff

If your staff doesn't feel a personal connection to your plan, it's not likely to be realized. So, it's important to involve them in the planning process as much as possible. This will help ensure that the success of the plan will pay off for everyone in the practice.

If your practice is small, you may be able to include your entire staff in the planning process. This is obviously less feasible if more than 30 or 40 people work in your practice, but you can still have all department supervisors participate, thus creating a link to everyone in the practice. The key is to make everyone feel that the strategic plan is "their baby," so they have a personal stake in bringing it to fruition.

Financial rewards must also be linked to supporting the objectives. In large part, employee behavior at any level in an organization reflects the economic reward system in effect. For example, if employee efforts are required to help the practice aggressively pursue growth or expansion opportunities, the employees in question need to see that they'll benefit if they do their part.

This is especially true with physician shareholders who may not otherwise benefit directly from capital investment in a new practice initiative. For example, if your practice wants to open a new satellite office, it's possible that a limited number of the physician shareholders would work in the new facility. However, the capital investment required to build and equip the office is a risk shared by all shareholders. For that reason, the compensation formula should provide a reward mechanism for all shareholders, separate from the compensation received by the physicians who provide patient care at the new office. Otherwise, why would a shareholder support capital investment in this opportunity?

Both professional and nonprofessional employees must have the skills necessary to achieve practice objectives in the manner and style dictated by your strategy. If they don't have the right skills, you'll need to train them.

If you determine that training would be too costly or difficult to acquire, your practice will have to hire other individual(s) who already possess the right skills.

Developing your financial plan

Budgeting is a critical component of business planning. Done correctly, a budget ensures that resources are efficiently used and that sufficient funds are allocated to the most critical components of your strategy. It's not uncommon for practices to consider a potential opportunity, only to have analysis indicate that the risk involved in the opportunity is too great, compared with the potential benefit.

For that reason, when your strategic plan is finalized, it should have two main parts: the narrative section, with all the elements discussed earlier (mission statement, assessments, goals, etc.) and a budget forecast. The latter takes the ideas in your plan and projects them into the future in order to forecast their financial impact.

The budget you develop in concert with your strategic plan should include two components:

Examining historical data. If you're planning for the next fiscal year, the budgeting process should begin in the practice's fourth fiscal quarter. You should also schedule your strategic planning meeting with this timing in mind.

Your historical review should include a detailed, line-item assessment of the profit and loss statement. Look carefully at revenue by provider and by key service line or location. Resist the temptation to simply apply a percentage adjustment factor for the next fiscal year; don't assume that the way things were done in the past is the way they should be done in the future.

Assessing future results. The table on page 116 provides an example of a budget forecast projecting the economic impact of adding a new optical dispensary to a practice. The analysis includes the number of expected jobs, the expected revenue rate and cost of goods sold per job, as well as operating expenses that will probably be generated by adding the dispensary. (The category "other expenses" includes items such as build-out costs, equipment and display cases.)

As you can see, the projection indicates that, if these assumptions are correct, the new dispensary should generate an operating profit margin of about 20%.

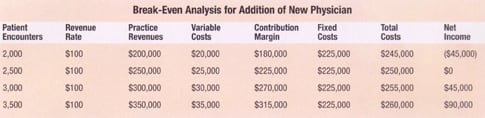

Before compiling your complete budget, you should examine individual key objectives by creating a "break-even analysis" for any that will have a financial impact. This will clarify exactly how much business the proposed change will need to generate in order for your practice to avoid losing money as a result of making the change. (For an example, see "Break-Even Analysis for Addition of New Physician," below.)

Evaluating your results

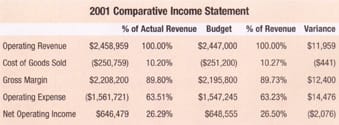

It's important to integrate the budget, including forecasts, into the practice's financial reporting. This will let you periodically compare actual results to the corresponding forecasts, providing a way to gauge how successful your efforts have been. It also makes it possible to manage the individuals responsible for implementation of the initiative and operating functions more objectively.

The table at the top of the page provides an example of a comparison of budgeted and actual numbers.

Creating a winning future

Having a clear practice strategy is a key factor in achieving success. But having a clear strategy isn't enough; you need to have a firm commitment to implementing your goals.

By creating a well-documented action plan, providing strong physician leadership and using financial tools to limit risk, you'll ensure that your strategic plan will translate into real practice success in the years ahead.

Bruce Maller is founder, president, and chief executive officer of The BSM Consulting Group. He often lectures for medical societies and at national conventions, including the annual ASCRS/ASOA meeting, and he's a frequent contributor to healthcare publications. He can be reached at bmaller@bsmconsulting.com.

|

Creating a Strategic Plan: A Quick Review |

Here's a brief summary of the steps involved in creating a strategic plan for your practice. (Note: For a more complete discussion of this process, see "Still Don't Have a Strategic Plan?" in the March, 2002 issue of Ophthalmology Management.) The strategic planning process, usually initiated at the request of the practice owner(s), begins with data gathering and data analysis. The most effective strategic plans result from several months of market research, preparation and pre-meeting discussions with the principal stakeholders. Once you've laid the groundwork, the principal practice stakeholders meet to work out the different aspects of your plan. In this meeting you should take the following steps:

Completing these tasks will enable you to create an action plan that can serve as an effective roadmap for your practice. |

|

Break-Even Analysis: Is the Objective Viable? |

| Conducting a break-even analysis will clarify whether a planned objective is financially viable by telling you approximately what level of business activity will be necessary to cover your expected costs. This tool is particularly useful when you want to evaluate expansion opportunities, new capital purchases, new services or new providers. Your projected expenses can be separated into two categories: fixed and variable. Fixed expenses, such as facility rental, most staffing costs and insurance, usually don't vary regardless of the number of patients you're treating (within reasonable limits). On the other hand, variable overhead expenses, such as the cost of goods associated with the sale of contact lenses, are proportional to your level of business activity. The chart at the bottom of page 120 provides an example of a break-even analysis for adding a new provider to a practice. As the chart shows, the practice will need to generate 2,500 new encounters at a revenue rate of $100 per encounter to cover expected fixed and variable costs. |