LASIK

Lawsuits -

Patients and

their lawyers take aim.

The number of

cases is increasing. How to protect and,

if necessary, defend yourself

By C. Gregory Tiemeier, J.D., Denver, Colo.

When asked why he robbed banks, Willie Sutton replied, "That's where they keep the money." The same can be said about why the number of LASIK lawsuits is increasing. Lawsuits follow accumulations of money, and public perception is that doctors who perform LASIK are becoming millionaires. Whether that's true or not for you, LASIK has caught the attention of plaintiffs' malpractice attorneys across the United States. Consider this recent headline from Lawyers Weekly USA: "Plaintiffs' Bar Trains Its Sights on Laser Eye Surgery -- Popularity and Profits May Yield Shoddy Procedures."

As you deal with these challenges, you may learn from the experiences of your colleagues who have, sometimes through no fault of their own, ended up as defendants in LASIK malpractice cases. The following examples and recommendations are drawn from existing LASIK lawsuits and my experiences defending ophthalmologists in both LASIK and RK litigation.

All eyes on marketing

The legal attention being focused on LASIK really shouldn't surprise us. Ophthalmologists and laser surgery centers have been informing the public about LASIK for years. Celebrity endorsements, multipage, full-color advertisements, contests and even tear-off coupons are used to persuade the public that they need LASIK. Even if the marketing isn't yours, the LASIK candidates who come to your office have been exposed to it, and if you're unlucky enough to be sued, the impaneled jurors will also have been exposed. This may account in part for the $1,258,000 verdict levied against an LCA-Vision center and its surgeon-owner who were sued in Buffalo, N.Y. Although not unheard of, $1.2 million is at the high end of verdicts for vision loss. LCA has appealed its portion of the verdict.

Unfortunately, LASIK long ago ceased to be thought of as surgery, and is now a luxury commodity, a mark of status. While plastic surgeons have been dealing with this for years, cosmetic surgery doesn't usually affect a person's ability to live and work on a day-to-day basis the way refractive surgery does. As a result, if something goes wrong, dollar damages can be more substantial and easier to quantify than in a cosmetic surgery case. Also, representations that a patient can "enjoy life without glasses" will probably be easier to prove or disprove than a more ethereal concept like beauty.

Consequently, although the notion of advertising refractive surgery is easily transplanted from its cousin, cosmetic surgery, it can create unwanted problems in its new environment. Make sure to think about your marketing campaign and patient interactions in the context of these key points:

- You can't deliver new eyes. You know that LASIK isn't a commodity. But you need to take that a step further: You and all of your staff members should treat it that way. With the willing complicity of some ophthalmologists, advertising executives have been treating refractive surgery as if it were a widescreen TV. The problem, of course, is people begin thinking of the surgery the same way they would the widescreen TV. If it doesn't work to their satisfaction, they want a new TV. Sears can back up its advertising promises by delivering a new TV. You're not able to deliver a new set of eyes, so reconsider advertising your services the same way Sears advertises its products.

- Patients are bombarded with ads. Whether or not you advertise, remember that many of your colleagues do. When a patient comes into your reception area wanting to know about LASIK, he probably already has preconceived notions about its safety and effectiveness. Step one in patient counseling is finding out what the patient already "knows" about the surgery. Step two is disabusing that patient of much of his "knowledge." Only then can you proceed to step three, which is advising him of the benefits, risks and alternatives.

- Your message must stand up to all interpretations.

Think about the messages you, your staff, and your advertisements give to prospective LASIK patients. Now picture yourself sitting on the witness stand, explaining to six people you've never met why each one of those messages is reasonable and accurate. If this image makes you feel uncomfortable, you need to change the message you're sending your patients.

For example, if you offer patients a discount for signing up for surgery on the day of a LASIK seminar, practice your response to this question, which isn't far from one you'd likely be asked on the witness stand: "Doctor, would you please explain to the jury how bribing a patient to make a snap decision to have eye surgery improves the informed consent process?" - Juries hold physicians to a high standard. Although P.T. Barnum may have been correct about the frequency with which suckers are born, people reasonably expect exaggeration of claims when the advertised product is a new kitchen gadget that slices, dices and makes julienne fries. Thankfully, juries hold physicians to a higher standard. Making overstated promises may not only breed cynicism, but also create legitimate issues of negligent misrepresentation or fraud in a lawsuit. LASIK is a great procedure, and 99% of your patients may be happy, but don't forget the other 1% when presenting this procedure to your patients, both in advertising and in person.

A case in point on overstated promises comes from Washington state, where three sisters, Ms. Janke, Ms. Harris and Ms. Stauffer, are the nucleus of a class action that is being prosecuted by the Seattle firm of Keller Rohrback against the Lexington Eye Institute of Surrey, British Columbia. The claims center on alleged violations of Washington's Consumer Protection Act (RCW 19.86 et seq.) wherein patients were allegedly bombarded with guaranties and build-ups of the LASIK procedure, but not informed of the risks until after they had paid for the procedure in full.

Declining the procedure after being informed of the risks allegedly resulted in a cancellation fee. Further, the patients were allegedly told they were "ideal candidates" by the co-managing optometrist, but this was disputed by an ophthalmologist who examined them after the surgery for complications.

In a May 14, 1996 letter on "Marketing of Refractive Eye Care Surgery: Guidance for Eye Care Providers," from the Boston Regional Office of the Federal Trade Commission, examples of misleading advertising were set forth. The letter stated the advertisers are responsible not only for claims that are expressly stated, but also those that are reasonably implied from the statements. "Throw away your eyeglasses" was specifically targeted as a suspect statement because patients with a good result may nonetheless need glasses for presbyopia or night driving. The letter also mentioned that statements about the safety or efficacy of refractive surgery should be accompanied by disclosures of the significant risks of the procedure, as well. These comments were also set forth in a joint letter to eyecare professionals from the FTC and the FDA dated May 7, 1996.

In the recent Lawyers Weekly article, improper patient selection was listed as one of the two major groups of refractive surgery malpractice cases. (The other was operator error.)

An ophthalmologist called me about a year ago during a patient counseling session. He told me that he was examining a 52-year-old man with vision in only one eye who wanted LASIK. The surgeon was curious about the legal ramifications of performing surgery. I suggested that he let some other ophthalmologist perform the surgery. The 52-year-old gentleman may well have been an appropriate candidate (in his one good eye), but the more significant question is whether the ophthalmologist should undertake the risk of operating. You must establish your own level of risk tolerance, the same way you would when you meet with your stockbroker.

The following examples, based on my prior experience, illustrate the types of situations where you must factor in the risk involved.

- Clinical findings. Know the difference between keratoconus, forme fruste keratoconus, and contact lens-induced inferior corneal steepening. And, more importantly, document the condition in the patient's chart and why it's appropriate to proceed with surgery. Do this before the operation. Most attorneys view subsequent amendments to the record as a problem at trial, much as keratoconus is a problem for LASIK. Can you do it? Yes. Is it likely to turn out well? No.

In one sad case, one ophthalmologist, apparently trying to improve his market share, informed a dissatisfied patient that another ophthalmologist had performed LASIK on her despite her "keratoconus." The patient only had inferior corneal steepening from previous contact-lens wear, but the innocent ophthalmologist had but one topography preoperatively to document this. Fortunately, however, multiple pachymetries had been performed by yet another ophthalmologist who had seen the patient shortly before for a LASIK consultation, and they showed no thinning.

If you have any questions about the appearance of a topography, be cautious for the patient's sake, and be thorough for your own sake. Topographies are an effective device not only for screening patients, but also for documenting the validity of your patient selection. The difference between keratoconus and inferior corneal steepening from contact-lens wear is shown by repeat topographies, not a single topography. If suspicion of either exists, repeat topographies would be helpful in documenting appropriate patient selection. - Contact-lens wear time. This seems to be a greater concern for attorneys than for some physicians. The question is raised in most lawsuits whether the patient was out of his contact lenses for enough time to accurately plan the surgery. Please keep in mind that "enough time" for one patient may not be the same for another. Be safe and measure two serial manifest refractions that are consistent. If you explain to the patient why you're being cautious, he'll appreciate it, rather than running to another eye surgeon to undergo LASIK 2 weeks sooner.

- Co-management. If you're in a co-management situation, who is handling the patient selection? If you're relying on other ophthalmologists or optometrists for preoperative evaluation and screening, you should know about their qualifications. How reliable are they, and their staff members? What education have they had about contraindications to LASIK? What are they telling your patients about candidacy for LASIK? A high myope may have a thick enough cornea for the surgery, but if full correction isn't obtained, will he have enough for a reoperation? If you offer free enhancements, this issue can become a serious point of contention with your patient.

- Patient personalities. Watch out for perfectionists. A disproportionately high number of them are engineers, lawyers, pilots and physicians. I also find that a disproportionately high number of them are plaintiffs after refractive surgery.

Patient expectation questionnaires, provided during the informed consent process, can be useful in determining which patients have unrealistic expectations. These patients can then be appropriately counseled. - Debatable contraindications. The most consistent complaint I've seen in all LASIK malpractice suits involves vision at night or in low light. Most surgeons seem to think this is related to pupil size, but others disagree. Even if you don't agree with this assessment, it's worthwhile to measure pupil size in low light, and advise the patients with large pupils of increased risk. Particularly in the courtroom, perception can become reality, and the majority opinion may prevail whether it's right or wrong.

The Seattle class action suit also touches on this aspect of patient selection. Allegedly, the three sisters had their pupils measured preoperatively and were found to have relatively small pupils and therefore didn't have large ablation zones. The postoperative examination by a surgeon at the University of Washington, however, resulted in a different opinion -- that the pupils were large and the patients should have been expected to have the problems with night vision that they complain of now.

Informed consent

In the context of elective surgery, informed consent becomes much more important than when you're sewing together a cornea after blunt trauma. The patient and the surgeon both have ample time to discuss the procedure, its benefits, risks and alternatives. If sufficient time isn't given, the jury may infer the worst.

In one radial keratotomy trial, the jury found in favor of the plaintiff on the issue of informed consent primarily because she had signed the consent form before talking to the surgeon. Unfortunately, the informed consent videotape had asked the patient to sign the consent form if she didn't have any questions for her doctor. At trial, of course, she recalled unanswered questions that apparently had not occurred to her after viewing the videotape. Timing is everything.

|

|

Claims and Payments |

|

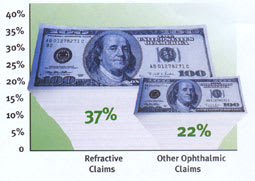

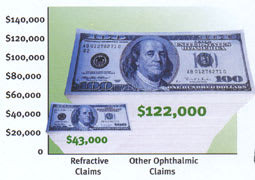

The Ophthalmic Mutual Insurance Company (OMIC) reports a significant increase in the number of its refractive surgery cases, most notably involving LASIK. The group considers the data collected so far to be preliminary because the majority of refractive cases are still open. However, it has noted two trends, which are illustrated in the charts below:

Percentage of OMIC claims settled with an indemnity payment to the plaintiff.

Average settlement payout to the plaintiff on OMIC claims. Source: Ophthalmic Mutual Insurance Company |

Here are some suggestions to decrease your chances of a lawsuit based on lack of informed consent.

- Know how videotape fits in. I'm frequently asked whether videotapes are appropriate for providing informed consent. My response is usually "the more, the better." Videotapes are a valuable adjunct to the informed consent process, and can provide valuable information without taking much staff time. They are not, however, a substitute for conversation with the surgeon or staff. One advantage of a videotape is that it can be shown to the jury at trial, so they can see exactly what the patient was informed of.

Replaying portions during cross-examination was particularly effective against one plaintiff who stupidly claimed he'd been guaranteed a perfect surgical result. - Know what your counselor is saying. In Colorado, there is no legal prohibition against delegating the discussion of risks and benefits and alternatives to a well-trained professional other than the surgeon. The surgeon, however, remains responsible for any failures on the part of the counselor. Thus, the duty can be delegated, but not the responsibility. (This may not be true in all states, and you should check with an experienced medical/legal attorney before delegating counseling responsibilities to a staff member.)

If you do delegate, make sure you know what your patients are being told. I'm surprised at the number of surgeons I've met who have never watched the videotapes or listened to the presentation given by their own staff members. - Keep your forms and conversations updated. Make sure your staff and your consent forms are keeping up with the times. Recently dry eyes after LASIK has become a major issue in patient satisfaction and refractive results. As recently as last fall, many standard consent forms didn't even mention dry eyes as a side effect, much less a complication that could affect vision quality. Although dry eye is usually a transient problem, keep in mind that patients like surprises for birthday parties, not after surgery.

The possibility of progressive myopia in high myopes with large ablation zones has also come under discussion recently. This is reminiscent of the progressive hyperopia that was discovered after many thousands of RK patients had surgery.

I spoke with one unfortunate surgeon who was found to be negligent in providing informed consent because he didn't inform an RK patient about progressive hyperopia, even though articles hadn't been published on the subject at the time the surgery was performed. You must keep abreast of developments in refractive surgery, and inform your patients accordingly. - Co-management risks. When working with a co-managing optometrist or ophthalmologist, you need to be on the same page with respect to informed consent. Giving conflicting or contradictory messages to the patient will be confusing at best and will cause the patient to question your competence at worst. Decide in advance with your co-managing doctors who will be providing informed consent, how it will be presented, and what will be said. This is important not only for the surgeon, but also for the referring doctor, who may be on the hook for a negligent referral if the surgeon is providing inadequate informed consent. There's nothing wrong with the patient receiving information from both the surgeon and the co-managing doctor, but both need to be aware of what the other is saying. (The surgeon is ultimately responsible for the consent of the patient.)

Preparing for surgery

As mentioned above, most LASIK lawsuits fall into the categories of improper patient selection or operator error. Here are some examples of operator error that have come across my desk. Simply being aware of them will help you avoid the same fate.

- Improperly assembled equipment. The spacer plates on your microkeratome are important. Make sure they're there before cutting. Look over the microkeratome each time it's handed to you. It only takes a few seconds.

In one case, an improperly assembled microkeratome resulted in entry into the anterior chamber. - Missed monovision correction. This situation often results in a lawsuit. The patient requests monovision, but full correction is performed on both eyes. As I've asked some plaintiffs' attorneys, what is the injury when the patient has 20/20 uncorrected vision? Nonetheless, because the average LASIK patient is older than 40, near vision is a significant consideration. If your staff handles most of the informed consent process, make it a habit when meeting with older patients before surgery to question them about monovision correction.

In one current case of this type, a plaintiff is so angry that she refuses to even consider settlement. She wants to litigate just to make the doctor miserable. - Incorrect axis of astigmatism. A zero may be nothing, but it can take on great importance when attached to the end of a "10." The difference between 10 and 100 is the difference between eliminating astigmatism and doubling it.

This occurred in one case where the autokeratometer printout was taped into the chart. The tape covered the last zero of the manifest refraction. Although this transcription error can occur even when everyone is as careful as they can be, review your processes to make sure appropriate checks are in place to ensure the accuracy of the prescription when it's entered into the laser database.

Managing dissatisfied patients

If patients don't get the results they expect from surgery, they'll be dissatisfied. (That's why, of course, it's so important that they have realistic expectations preoperatively.) As a surgeon, you may not be inclined to spend a lot of time with these unhappy patients, particularly if you believe they got a good result and they're just being picky.

Do the opposite. Spend time with them. Explain what happened. Explain what their options are, what may work and what may not. Explain that advances in technology may be able to eliminate that central island, if they can wait for a year or two and use a contact lens in the meantime.

I wish I could say that this will always work and patients won't sue, but I can't. I've seen the same complication occur with patients of different ophthalmologists; both ophthalmologists go out of their way to counsel and help the patient. One gets sued and the other doesn't. Do it anyway. The worst that can happen is you'll have the opportunity to testify on the witness stand about all the measures you undertook to help this patient, pulling out all the stops in your pursuit of their satisfaction.

One caveat: If you do pull out all the stops, exercise some caution and common sense in offering the patient reparative treatments. If you offer a procedure that is an off-label use of your laser, or is new and relatively untried, share this information with the patient. Be candid. And then write what you told him in the chart. If the procedure doesn't work as planned and you're sued, you won't have the additional burden of a claim that you were using the plaintiff as a guinea pig.

I have two cases on my desk that involve allegations that the doctor was experimenting on the patient by offering new, untried therapies, such as transepithelial PRK and lamellar keratoplasty. The doctor was legitimately doing his best to give the patients the most up-to-the-minute technology to address their complaints, but his efforts backfired when the patients found their way to a lawyer. Keep in mind the maxims that no good deed goes unpunished, and if anything can go wrong, it will. If you're offering anything out of the mainstream, discuss it thoroughly with the patient and document the discussion in detail.

Litigating the LASIK malpractice claim

If you find yourself the target of a lawsuit, don't be afraid to educate your lawyer. You know more about this than lawyers do, and your help will be invaluable.

First, keep in mind that proving or disproving vision loss is a challenge. Notwithstanding the new wavefront technology, it can be difficult to prove that a plaintiff is able to see the 20/20 line when he steadfastly maintained at each office visit he could only read the 20/100 line.

In fact, the latest trend in refractive surgery lawsuits is for plaintiffs to reject Snellen visual acuity as a vision test, in favor of the more subjective and difficult to define "quality of vision." Although there are undoubtedly legitimate differences between being able to read a high-contrast Snellen visual acuity chart and recognizing lower-contrast objects, reason seems to have been lost in the pursuit of dollars. An entire cottage industry is springing up to prove vision loss in refractive surgery lawsuits. Patients with 20/30 uncorrected vision (correctable to 20/20) are passed off as visually incapacitated due to low contrast sensitivity.

The department of motor vehicles can be helpful in this area, however. Make sure your lawyer asks the plaintiff for a copy of his drivers license application and driving record. I'm continually befuddled by the number of plaintiffs who maintained they were unable to drive, but nonetheless had obtained an unrestricted drivers license after having refractive surgery. So far, juries have rejected the explanations given for the inconsistency.

Also be aware that despite apparently legitimate credentials, some experts use questionable methods to gain employment as plaintiff's experts.

In one case, a driving simulator was used to establish vision loss. While this may not be inherently unreasonable, your lawyer must look at how the test is performed and what controls are used to ensure that full effort is given.

The expert in my case had used none whatsoever, relying only on the integrity of the plaintiff and ignoring the well-documented effect of secondary gain. Exaggeration of vision problems is the rule in malpractice cases, and it's important that the examining physicians, whether they're on the plaintiff's or defendant's side, use some method of testing the reliability of the patient's subjective responses.

Another example of exaggeration of vision problems comes from a current LASIK case in which the plaintiff ostensibly had uncorrected vision of 20/100+1. The eye was tested using a phoropter, with a plano sphere refraction. Her acuity dropped to 20/200. A cycloplegic refraction by another ophthalmologist improved her vision by four lines over her manifest refraction result.

I can safely say that in the majority of refractive surgery lawsuits, plaintiffs exaggerate their vision loss significantly, and sometimes make claims that defy common sense. When was the last time you saw a patient with mild irregular astigmatism who suffered from monocular diplopia with a good-fitting gas permeable contact lens? Lawsuits tend to bring out claims like this.

Think logically about the use at trial of exhibits that purport to demonstrate vision loss. Is the premise that supports the exhibit scientifically valid? If not, let your lawyer know. During some trials, plaintiffs have offered to show pictures of what a visually disabled patient "sees," so the jury can understand the injury. I can't help but wonder how a visually disabled plaintiff can select a photograph that accurately represents his vision loss, when the substance of the claim is that he can't see.

Knowing yourself is your best defense

The information in this article is provided to educate you, not to tell you how to run your practice. Even following all the suggestions given above won't guarantee a litigation-free career. The defendants in the illustrative cases are generally well-trained, well-qualified ophthalmic surgeons who were in the wrong place at the wrong time. The only sure way to avoid all risk is to not see patients.

Determine what level of risk you're willing to accept, and proceed accordingly. Incorporate the suggestions that will fit into your practice, and adapt or ignore the ones that don't. Hopefully, you can learn something from the experiences of your colleagues.

C. Gregory Tiemeier is a medical malpractice defense lawyer in Denver, Colo. He's been defending refractive surgery cases since he was licensed to practice law in 1986. He has represented ophthalmologists in more than 20 refractive surgery malpractice claims.

|

Examining Your Ad Campaign |

For several years now, the Federal Trade Commission, the American Academy of Ophthalmology and other eyecare organizations have been working together to educate refractive surgeons on legal and ethical advertising. Many ads still lack proper disclaimers and fail to mention the risks, thus leaving doctors vulnerable to sanctions and patient litigation. But the FTC and the Academy have seen an overall improvement in advertising practices. "We're seeing far fewer of the misleading 'Throw away your glasses' claims," says Matt Daynard from the FTC's Division of Advertising Practices. "Education seems to be working. The number of ads considered troublesome has declined in the past year." Daynard and Richard L. Abbott, M.D., the Academy's senior secretary for ophthalmic practice, say you should screen all of your advertisements for claims or statements that are false, deceptive or misleading in any way -- and that you're responsible for claims that are reasonably implied from your advertisements, as well as claims that are expressly stated. For example:

The Academy's Code of Ethics addresses these issues, as does one of its CME courses at www.eyenet.org/aaoweb1/OEC/384.cfm. To read the FTC's Marketing of Refractive Eye Care Surgery: Guidance for Eye Care Providers, visit www.ftc.gov/bcp/guides/eyecare2.htm. --Ophthalmology Management |