The

Business of Ophthalmology

From Now to 2010

By Louis Pilla

With complex dynamics and interrelated players, health care defies prediction. But in conversations with various experts, trends shaping health care begin to emerge. From the shifting tides of population demographics to advances in pharmaceuticals, these forces will arrive at your office's doorstep, perhaps sooner than you think.

In this article, we'll discuss the major forces likely to shape ophthalmology during the next decade. What's more, we'll offer practical guidelines about coping with and perhaps flourishing amid these changes.

|

Specialty Certification Plans of Graduating Medical Students |

||

| Year | Total number of students declaring specialty choice | Percent of students choosing ophthalmology as their specialty |

| 1991 | 7,749 | 3.4% |

| 1992 | 8,062 | 3.4% |

| 1993 | 8,128 | 3.2% |

| 1994 | 8,410 | 3.4% |

| 1995 | 9,179 | 3.0% |

| 1996 | 8,844 | 2.7% |

| 1997 | 8,448 | 2.3% |

| 1998 | 8,197 | 2.4% |

| 1999 | 11,472 | 2.7% |

| 2000 | 12,779 | 3.0% |

| Source: Association of American Medical Colleges, Washington, D.C. | ||

Meeting increased demand

Of all the trends shaping health care in America, and by extension ophthalmology, the aging population is likely to have one of the most lasting effects.

Because older patients make up a large part of ophthalmologists' patient base, the increased number of seniors is likely to raise the need for ophthalmologists' skills. "We're going to be seeing a lot of demand for ophthalmology services," says George Blankenship, Jr., M.D., immediate-past president of the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO). A growing Medicare population, according to Richard Lee, M.D., AAO secretary for practice management, could mean that "we would have a lot of patients requiring a lot of health care."

|

Managing Managed Care |

|

Consultant Gil Weber, MBA, offers these strategies for working with managed care: Understand what it costs you to provide care. If you know what it costs you to deliver one RVU, you can figure out what it costs to provide every service you deliver. With this information, you can determine whether you'll make or lose money with the reimbursements offered. Be willing to say no. Decide to terminate marginal or money-losing existing contracts and turn down offers of inadequate new contracts. Instead, focus your efforts on building your practice with better-paying plans and cultivating private-pay patients. Don't panic. Don't panic about needing a contract or losing access to patients. "You don't take market share to the bank, you take profitable patients to the bank," Weber says. "A waiting room full of patients does you no good if you don't make money on every one of them." Empower your practice administrator to manage your -- Louis Pilla |

|

Figures from the U.S. Census Bureau back up these assessments. One projection, based on 1990 data, reveals an increase of more than 18.5 million people age 65 and older between 2001 and 2020.

For the next 10 years, though, you may not see a dramatic impact on your practice from the aging population. From 1990 to 2010, according to the Census Bureau, the elderly growth rate will be lower than during any 20-year period since 1910. In fact, the 2000 census revealed that during 1990 to 2000, the 65-and-over population increased at a slower rate than the overall population for the first time in the history of the census.

But after 2010, watch out. "An elderly population explosion between 2010 and 2030 is inevitable as the Baby Boom generation reaches age 65," according to the census report.

Still, Americans will be living longer during the next 10 years, notes the Health and Health Care 2010 report, prepared by the nonprofit research firm the Institute for the Future (Jossey-Bass Publishers). Without question, they'll need more ophthalmic services. By 2010, the report notes, the average life expectancy will be up to 86 years for women and 76 for men.

"This is the opportunity for an ophthalmologist who is going to be practicing for the next 20 years to think about how to meet this increased demand," says Lee of the AAO.

Various areas are key for addressing the "abundant service need" of baby boomers, says practice management consultant John Pinto, president of J. Pinto and Associates, Inc., San Diego, Calif. They include practice efficiency and meeting this patient's high expectations for technology, skills, and the physical office setting -- all in an environment of declining payments. (See "Dealing with Increasing Labor Costs," and "Practice Consolidation to Continue".)

Supply of practitioners

With this rise in the senior population, will there be enough ophthalmologists to treat them and other patients during the next 10 years? Statistics seem to indicate that ophthalmologists will be in ready supply, and that, perhaps, an oversupply might materialize.

After efforts to reduce the number of residency slots during the height of managed care, the number of slots is beginning to increase to previous levels, according to the AAO's Lee. Directors of residency programs, he notes, anticipate getting back to the number of slots before managed care entered the picture. For the academic year ending June 30, 2002, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACMGE) counts 122 ACMGE-accreditated ophthalmology residency programs with 1,363 residents.

Statistics from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) suggest that more students are beginning to choose ophthalmology as a specialty area. In 1997, 2.3% of 8,448 surveyed graduating medical students (194 students) who declared their specialty choice indicated ophthalmology as their specialty area. By 2000, that number had risen to 3.0% of 12,779 students (383 students). (See "Specialty Certification Plans".)

Other sources told Ophthalmology Management that it's possible those numbers reflect the rise, but not necessarily the recent slowdown, in laser vision correction. In other words, once medical students realize that laser vision correction isn't necessarily a success slam-dunk, fewer might choose ophthalmology as a career.

While not pinpointing ophthalmology specifically, Health and Health Care 2010 notes that the specialist-to-population ratio is expected to reach 152 per 100,000 population in 2010, up from 140 per 100,000 population in 2000. This suggests an oversupply of specialists, as "even the highest estimates of specialist demand lie well below the projected supply of 152 per 100,000 population."

In contrast, the overall number of applicants to U.S. medical schools has been in serious decline. The 2001-2002 applicant pool of 34,859 represents a 6% decrease in applicants from 2000-2001, according to the AAMC. And that's a drop of more than 12,000 applicants from 1996, when the applicant base reached 46,965. Among the reasons proposed for the decline: the high cost of medical school; a view that medicine offers less independence than previously; and a decline in respect for the profession.

The prospect of an oversupply of eyecare providers is put forth in the widely noted 1995 Rand study "Estimating Eye Care Provider Supply and Workforce Requirements." Relative to public health need, the study found that the excess supply of eyecare providers ranged between 8,000 and 14,000 full-time-equivalent (FTE) eyecare providers. (An FTE was defined as providing 2,016 hours of patient care work each year.) But, the study notes, the excess supply varies widely depending on whether optometrists or ophthalmologists are the primary providers.

Although optometrists are in oversupply in all models the report examined, no excess of ophthalmologists exists when ophthalmologists are the primary care providers. But when optometrists are the primary providers, a surplus of more than 6,000 ophthalmologists occurs.

While notable, various considerations temper these results. For instance, the Rand study didn't account for advances in either refractive surgery or photodynamic therapy, both of which increase workloads, notes Paul P. Lee, M.D., lead author of the study and professor of ophthalmology at Duke University Medical Center. Also, because the data hasn't been updated, the findings' utility is "of limited scope at this point in time."

One other factor to consider: The pace of new graduates may not be enough to replace ophthalmologists in their 50s and 60s who will gradually reduce their workloads, suggests consultant Pinto. As we have an age wave in population, he notes, we may have the same phenomenon in ophthalmology.

Clinicians who choose to join the profession are likely to be happy with their choice. For instance, an AAO survey, according to Dr. Blankenship, found a substantial increase in satisfaction with the profession. Specifically, in a 2001 survey of 732 AAO U.S. members and fellows, some 60% of ophthalmologists said they were extremely or very satisfied with their profession. That's up from 45% in 1999 and 54% in 1998.

What's more, 79% of surveyed ophthalmologists in 2001 said they were extremely or very satisfied with ophthalmology as a career choice, compared with 72% in 1999. (The 1998 survey didn't pose the question.)

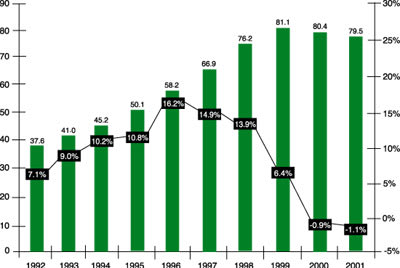

Total HMO Enrollment and Growth Rate: Jan. 1992 to Jan. 2001

Managed care might change, but not go away

Besides the forces of population and provider supply, you'll continue to contend with managed care. As much as it may rankle, this system is likely to exert significant influence on health care during the next decade.

By 2005, according to Health and Health Care 2010, health maintenance organizations (HMOs) will capture the majority of the commercial market and more than 25% of the Medicare market (which we'll discuss in a moment). HMOs, the report says, will cement their position as the dominant form of health insurance over the next decade. Preferred provider organizations (PPOs) will have some durability, but pure indemnity will decline rapidly in importance.

Of note, however, is that the historic increase in HMO enrollments has recently flattened. From 1999 to 2001, HMO enrollment decreased from 81.1 million to 79.5 million, according to the research firm InterStudy Publications. (See "Total HMO Enrollment and Growth Rate," on page 34.) These figures don't account for PPOs.

Similarly, the number of HMOs in the United States continues to drop, InterStudy notes. The total number of HMOs reached 541 as of January 2001, down from 568 in January 2000. InterStudy attributes the decline to industry mergers, plan consolidations, and plan closures.

Whatever the number of HMOs in the future, you're likely to contend with a more confusing payer landscape. "The health insurance market will evolve into a mix of different health plan models, many of which will spend the next several years in a constant flurry of reorganizations and mergers," says Health and Health Care 2010. In 2007, close to 50% of the population will be in health plans for which cost containment is an issue.

As you might expect, ophthalmology experts have little good to say about managed care. "Managed care is a very bad idea whose time has come and gone," says I. Howard Fine, M.D., president of the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery (ASCRS). "Managed care was not ever about care, it was about money."

"Managed care drives the marketplace out of fear," asserts Gil Weber, MBA, a Florida-based practice management and managed care consultant.

You can't have a situation, Dr. Fine notes, in which the doctor's aims and goals are different than the desire and will of the patient. "We have structured managed care in such a way that the primary care physician's major motive is the conservation of resources and the patient's desire to get well is secondary."

Patients have to realize, he continues, that managed care inverts the usual insurance system. Traditionally, medical insurance involved patients paying for routine, small-ticket items and insuring themselves against big-ticket items. "Along came managed care, which provided no cost for small-ticket items and then fights the patients when they want a big-ticket item covered."

Still, the future may hold a brighter outlook for ophthalmologists and managed care, suggests Weber. Although some health plans will always offer poor deals, in the next few years he forecasts a "general inching up of fees because doctors are no longer driven by panic. They're willing to say no to bad contracts, and health plans have a harder time playing doctors against one other."

Ophthalmologists, he says, are evaluating contracts more carefully. As they become more business-savvy, they're more willing to drop current contracts that are marginal or inadequate. "No contract," he stresses, "is better than a bad contract." (See "Managing Managed Care," on page 36.)

And with the public's perception that managed care might deny or delay access to health care, "plans are under enormous pressure to do the right thing," Weber says. Some state insurance commissioners are acting aggressively against health plans that don't pay claims on time or downcode claims, he says.

What's more, various managed care plans are rethinking how to deliver the routine vision exam and optical benefit. Some plans, he notes, are trimming the optical benefit entirely while others put more cost on the patient. "Anytime patients are taken out of a prepaid benefit, which doesn't pay the doctor particularly well, and put back in the fee-for-service, cash-money marketplace, that's a positive for the eye doctor."

Medicare managed care: gradual demise?

Like HMO enrollments, participation in Medicare managed care has also declined. As of January 1, 2001, there were 6.1 million HMO Medicare enrollees, 7.2% fewer than the preceding year, according to InterStudy. And government data suggest that another half-million Medicare+Choice enrollees will be affected by partial or complete pullouts of managed care firms in 2002, InterStudy says.

Medicare HMOs are suffering a gradual demise, Weber says. Some are leaving the market; those that stay are cutting back or modifying benefits.

The result may be positive for ophthalmologists, he suggests. Many seniors signed with Medicare managed care plans for coverage of routine eye exams and eyeglasses, which aren't covered by traditional Medicare. But if the plan goes out of business or drops this coverage, the member has no incentive to join. Those patients probably will return to the fee-for-service market for routine exams and eye wear. "As Medicare plans drop vision and eyeglass benefits, that's a positive for eye doctors," he says.

Taking a contrary view, Health and Health Care 2010 notes that many Medicare recipients will be in organized health plan arrangements like HMOs as opposed to fee-for-service programs. Changing Medicare so that it can afford to cover the great number of baby boomers retiring after 2010 will be dealt with later in the decade, the report says.

Medicare: "constant tinkering"

Whatever happens with Medicare managed care, there's little doubt that Medicare itself will remain a major force in ophthalmology in the next 10 years. In fact, "ophthalmology will be increasingly dependent on Medicare," says Dr. Blankenship.

At least one statistic backs up his view. The population insured through Medicare will increase at a slightly faster rate than the rate of overall population growth, increasing from just under 38 million (14.2% of the population) to 49 million (16.8%) in 2010, according to Health and Health Care 2010.

This forecast is made from a background of significant change in Medicare payments for ophthalmologists. Ophthalmologists experienced a 6.1% dip in Medicare payments from 1997 to 1998, according to a recent analysis published in Health Affairs. The decline in payments for ophthalmologists was second only to cardiothoracic surgeons, who saw a 7.7% decrease. The report also notes that Medicare payments for cataract removals by 2002 will decline by 23% over 1998 reimbursements.

Expect to see "constant tinkering" with Medicare, Dr. Blankenship says. Although he feels that all health care is undervalued in the United States, ophthalmology has done reasonably well working with Medicare to get appropriate reimbursement rates, and that will continue. "Medicare," he says, "will continue to support ophthalmologists and our practice in providing care for these patients."

More specifically, refractive lens exchange, which we'll discuss in a moment, will relieve Medicare of the big expense of cataract surgery, says Dr. Fine.

You might also expect to see Medicare reform efforts, such as the Medicare Education and Regulatory Fairness Act, introduced in Congress last year. One of its provisions would limit Medicare audits.

"There's no question that the amount of regulations that confront an office today are just staggering and often very conflicting," says Dr. Blankenship. During the next 5 to 10 years, he sees an overall reduction in government and regulatory agency intrusion into ophthalmology. Lobbying by physician groups, documentation of increasing costs from complying with regulations, and patient advocacy will drive these relief efforts.

|

|

Dealing with Increasing Labor Costs |

|

Although increasing staff productivity has been one anthem for reaching higher profits, ophthalmology practices may no longer be able to sing that song to such great effect, suggests San Diego-based consultant John Pinto. When it comes to staff productivity, ophthalmology has "hit the wall in the last 10 years," he says. Because the average ophthalmology practice spends between 18% and 30% of every dollar on labor, any movement on labor costs will probably have a big effect on the bottom line for most practices. Technology has been seen as one way to increase labor productivity. But that may no longer have as large an impact, he feels. At least empirically, he notes, so-called labor-saving devices, beyond patient accounts management computer systems, haven't had an appreciable impact on ophthalmic staff efficiency. Indeed, some technology offered today actually decreases staff productivity, he suggests. So, with increasing labor costs, Pinto warns of a "scissoring effect" between increasing labor costs and decreasing revenues. If labor costs rise, say 3% per year, and revenues from Medicare reimbursement and managed care decline by 3% per year, the ophthalmologist is left with a net loss -- one probably closer to 7% than 6% because of the disproportionately large impact of lowered Medicare and managed care payments on revenues. How to respond? Pinto suggests three strategies:

--Louis Pilla |

The future of co-management

If you're co-managing patients with optometrists, expect that you'll continue to do so. Also, the increasing tendency for ophthalmologists and optometrists to work together in a corporate structure is positive, says Dr. Blankenship. "I think we'll see more of that as we go ahead -- practices that are a mix of ophthalmologists and optometrists.

"There will be a tiering, a stratification of responsibilities that will be increasingly determined by the practice itself," he says. "An awful lot of that in reality takes place today and more of that will occur." Don Williamson, O.D., chair of the American Optometric Association's (AOA) federal relations committee, agrees that you can expect to see more practices that are a mix of ophthalmologists and optometrists.

Notably, the AOA, as well as the AAO and ASCRS in a joint paper, have issued statements that condemn putting financial interests before patient care concerns in any co-management or referral relationship. However, the AOA and the AAO-ASCRS joint paper seem to disagree on whether co-management relationships between ophthalmologists and optometrists can be routine.

Technology advances

Besides these trends, expect notable shifts from advances in technology. Of these, refractive implant surgery, including lens exchange and phakic IOLs, is the most potentially transformative.

"What I see happening is that refractive lens exchange is going to become the dominant procedure in the next 10 years," says Dr. Fine of the ASCRS. "We already are seeing refractive lens exchange taking place with excellent results and we haven't even begun to scratch the surface in terms of some of the new technologies on the horizon."

The ability to accurately calculate lens power and select the proper lens to address all of the patient's refractive errors, including presbyopia, myopia, hyperopia, and astigmatism, is going to direct people into refractive lens exchange as the preferred surgical technique, Dr. Fine suggests. Preliminary indications, says Patrick King, head of global marketing for CIBA Vision Surgical Division, suggest that phakic IOL surgery could cover the vast majority of myopia and hyperopia.

At present, the amount of refractive implant surgery being done represents the "tip of the iceberg," says Dan McWard, vice president, Global Surgical Business, for Allergan. The market for the entire refractive area, including implants and LASIK, could grow "10 times bigger than the cataract market could ever imagine to be."

One major advantage is the relative ease with which most ophthalmologists can bring refractive implant procedures into their practices. The surgery doesn't involve purchasing a big-ticket item like an excimer laser, for instance. "You don't have a big hurdle to get past before you can start doing it, as you did with LASIK," says McWard. "We just see that as you go out toward the end of this decade, you're going to be doing a lot of different implantable devices to correct vision."

"This is technology that is familiar to almost all ophthalmologists," says Dr. Fine. "A small percent of ophthalmologists do refractive surgery with lasers. But all ophthalmologists are into cataract and implant surgery."

Glenn Hagele, executive director of the patient/consumer group Council for Refractive Surgery Quality Assurance, is somewhat less excited about the future of refractive implant surgery. LASIK, he points out, has great brand identification as opposed to implants.

What's more, many surgeons will have to climb a learning curve for refractive implant procedures. Also, the equipment and staff required will be significantly different from a LASIK setup. He also suggests that a surgeon might be able to perform 2.5 LASIK procedures in the time it takes to perform one implant.

Although implantable devices will play a role in the future, especially for patients with high refractive errors, laser surgery is still the "biggest game in town," says Tim Sear, chairman, president and CEO of Alcon Laboratories Inc. Alcon, he says, has put a number of lasers into the field in the past months, and he expects that trend to continue. Physicians, he feels, prefer to have a range of choices to treat eye conditions, not just one method.

Don't expect to see a waning in the trend of practice consolidation. That, at least, is the estimate of Darrell Schryver, DPA, managing principal at the Denver-based Medical Group Management Association consulting group. For the foreseeable future, expect ophthalmology practices to merge and develop the "full spectrum of ophthalmology services," he says. Really successful groups now have subspecialization within the group, such as glaucoma and retina services, according to Schryver. Because those groups are getting larger and have more volume, they can support more ancillary services, such as testing that often was prohibitive because of equipment cost. That training programs are becoming specialized also dictates what private practices will look like, he says. Not just ophthalmology, but other specialties like cardiology and orthopedics have seen a growing push toward consolidation, according to Schryver. --Louis Pilla |

|

"Decade of the retina"

In the next decade, expect to see more pharmaceutical innovation that addresses the back of the eye. Technology and research have taken us "from simple corneal eye drops to posterior/anterior chamber lenses until we've now found our way to the optic nerve and the retina," says Dan Myers, president of Novartis Ophthalmics North America. Perhaps that suggests that this is the "decade of the retina," he says.

"Now we're looking at the eye as a whole," according to Mark Sieczkarek, senior vice president and president, the Americas Region, for Bausch & Lomb.

The retina holds the potential for the biggest changes in pharmaceuticals during the next 10 years, agrees Hans-Peter Pfleger, vice president, Global Marketing, Eye Care, for Allergan. Various companies, he notes, are conducting significant research to find anti-angiogenic compounds. "We're fairly confident we'll be advancing the treatment of anti-angiogenesis over the near term and certainly within this decade," asserts Myers.

For glaucoma, several efforts are under way to develop neuroprotective medications for the disease, notes Pfleger. Such medications represent "a completely new approach," he says.

Simpler dosing will also come into play in glaucoma treatment. Pfleger suggests that a trend toward highly effective, once-a-day medications will continue. Medications in gel formulations, which have the convenience of a daily drop with the longer-lasting potential of ointment, might help reduce the "incredibly onerous" dosing some glaucoma patients must bear, says Myers.

As for genomics, which garners all sorts of attention these days, Myers would be surprised to see products delivered this decade that would benefit patients.

Contact lens convenience

Convenience is also one of the watchwords for contact lenses. As in the past, manufacturers are trying to make contacts easier to use and maintain. During the next 3 to 5 years, expect to see the new category of "single-use lenses" develop, says Richard Weisbarth, O.D., executive director of professional services at CIBA Vision. This trend involves daily disposable lenses and 30-day-and-night continuous-wear products.

Besides convenience, the daily disposables represent a healthy method of lens wear. Such issues as allergic reactions to lens solutions or protein buildup go away, he notes.

Because vision correction is so popular, the development of advances like refractive implants won't harm the contact lens business, Weisbarth says. There are "plenty of eyes to go around for all the different vision correction options available," he says.

More changes

Various other advances likely will shift the ophthalmic landscape in the next 10 years. Among the possibilities, according to Scott MacRae, M.D., professor of ophthalmology and visual science, University of Rochester Medical Center, are wavefront sensing and adaptive optics. He is also medical director of the Alliance for Vision Excellence, a research partnership between B&L and the University of Rochester.

Clinicians may use wavefront sensing to not only screen or perhaps refract patients but also to characterize disease optically. Adaptive optics, which allows the viewing of greater detail of the retina, may allow clinicians to isolate individual retinal cells and deliver various treatments, such as those involving lasers.

Finally, Novartis's Myers sees one more potential advance in delivering ophthalmic services to patients. "We have," he says "the only organ in the body that's Internet ready." Combining cameras and computers, physicians might be able to diagnose various conditions online.

"Only going to get better"

Overall, reasons abound to be optimistic about ophthalmology. From a business perspective, the profession has less volatility than others. "Health care as a broad field and ophthalmology in particular are pretty high on the list of what people will spend money on," suggests Pinto. Noting that demographics and other factors mean the news going forward is "overwhelmingly positive," he feels that ophthalmology "in the main will sail through any kind of economic dislocation."

From a patient care perspective, the outlook is positive as well. "Medically and technically, we're entering a period when a lot's going to be accomplished," says Dr. Blankenship.

"Clearly there has never been a time when we could offer so much to so many people to enhance the quality of their life by improving and maintaining their sight," he says. "This is only going to get better." OM

Pilla is a freelance journalist specializing in health care topics. He is based in Horsham, Pa.

|

Open Access: The Future of Care? |

Some day, your practice might offer same-day appointments for nonemergent patients. Sound far-fetched? It's not, if you consider the results of a program involving the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Rochester Medical Center. Based at Strong Memorial Hospital, the effort was part of the department's participation in a program from the Boston-based Institute for Health care Improvement. Called the Idealized Design of Clinical Office Practices (IDCOP), the initiative takes a fresh look at how the clinical office functions. The IDCOP model consists of four pillars: access, interaction, reliability, and vitality. This effort focused on access. The department includes full-time faculty clinicians, residents, and support staff, according to Terry Meacham, R.N., the department's clinical manager. The program's aim, he notes, was to turn three faculty practices into one group, while streamlining the residency practice and improving the department's overall efficiency. At one time, routine patients could wait as long as 2 months for an appointment, resulting in a high fail-to-show rate and loss of follow-up. To work down the patient backlog, the department offered every client who called for a routine or follow-up appointment the same day or next session. During roughly 2 months, the department was able to get every patient who called for an appointment to come in during 3 weeks or less. Today, the department offers same-day or next-session appointments if possible, and all patients should be able to have an appointment within a week. The program had the unanticipated effect of dramatically decreasing the number of patients at other hospital-based practices staffed by residents, Meacham says. Hearing of shorter waits at Strong, they scheduled appointments there. This effort wasn't a walk-in program, stresses Gordon Moore, M.D., assistant quality officer at the Medical Center, who facilitated the effort. "By the way," he notes, "we've never seen a better practice-grower than open-access appointments." --Louis Pilla |